So, it turns out the past few days have been spent in a small room not of my choosing. BUT I had my faithful MacBookPro and wifi…and what else does a writer need? A sexier nurse would be nice, but here’s 25 pages of completely unedited text, not even one attempt at proofreading. Raw, I think you’d say. I may be home in a week or so, so I’ll continue working on this, as well as the last chapter of Elemental Mysteries.

OutBound

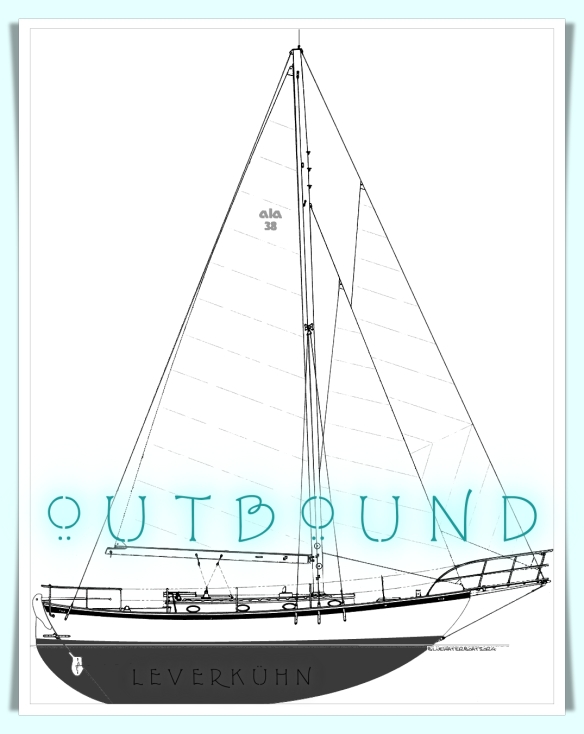

I’m sitting in my little inflatable, puttering through the anchorage off the town of Avalon, California, and it all looks so familiar. The beach is not quite a hundred feet away, the old casino still majestically presides over the harbor – now, and as it has all my life. The water below is still clear and deep blue, the white sandy bottom visible forty feet down, as relentlessly clear and full of promise now as it was in the late 60s. Nothing appears to have changed all that much out here, even my boat. Troubadour, my Alajuela 38, has seen a few miles under her keel, true enough, but she’s been in good hands all her life. My hands, as a matter of fact. And I’m looking at those hands as I ride through the anchorage off Avalon, the same hands that have cared for that boat over the last fifty years. My hands have changed a lot, and there are days I hardly recognize them, but when those moments find me I wonder what happened to time.

I remember looking at my grandfather’s hands once and wondering what all those brown spots were. Why his fingernails were kind of yellow and ridged. He had scars all over them, most from cuts he’d sewn up himself. He’d dip a needle and thread in whiskey and just sew himself up, and he didn’t think anything of it. It was what you did to stop the bleeding, so he did it and moved on to the next chore, which was what I did – more or less – over the years. Now, looking at my hand on the outboard motor’s tiller I recognized those hands again. They were mine, in a way, but they were my grandfather’s, too.

We sat and watched the Petrified Forest one night, that movie with Bogart and Davis, and he told me about his trip west in 1916. How there weren’t highways, not even a through road. He had a car, God knows how he afforded it, but he and my grandmother made the trip west together – from northeast Texas to Los Angeles. A few cities had paved streets but by and large the roads that connected cities were primitive affairs, often little more than sandy tracks through desert scrub. With the hard, narrow tires that cars had in those days, the wheels sunk down in the sand so deep that drive shafts were worn down by the mud and the sand, and he had to replace two solid steel shafts between El Paso and Flagstaff. Just polished down to nothing, worn down by the miles. Took them almost two weeks to make the trip, and he admitted to me that night he should have taken the train and bought a car once he got to LA, but that wasn’t my grandfather’s ethos. He wanted to get out there in the world, smell the road, meet people along the way and maybe have some fun and get in trouble too, because that’s what life was all about. I guess he passed that on to me, for better or worse, but I bought Troubadour and sailed away.

I didn’t plan things that way, however. Things just kind of happened.

The way things kind of happen. Unexpected things, the kind of people you never thought you’d run into, not in a million years. Doing things I never wanted to do, going places that held no interest to me. Life for me, before Troubadour, had been like the first thirty seconds of a roller coaster ride, the part where the ratcheting chain hauls you up the first huge incline. I was in the lead car right about then, looking out at the world during that little pause, just before the car takes off down that first steep drop. There’s this moment of anticipation, then a little exhilaration – soon followed by a dawning awareness that life might be far more interesting elsewhere, anywhere else than on a roller coaster. I never felt it in that moment before the fall, but about half way through my ride I began to develop an appreciation for smooth bicycles on warm country roads.

Which, I think, makes Troubadour all the more ironic. Troubadour has been a nonstop roller coaster ride, yet she’s like an old friend now. I know her aches and pains, her ups and downs, as well as I know my own – yet what makes that such an off-putting idea is she’s not flesh and bones. She’s a boat. A boat that became my life.

+++++

I started playing the piano in kindergarten, maybe a little before. I was pretty good too, for a five year old. My teacher, a crusty old man who kept a regal old Steinway grand in his music room, seemed to think I had talent, but I was always more interested in composing music, not playing. And not to make to big a deal about it, but I always hated performing in front of people. My first recital was a disaster, and that set the stage for many more over the years, and I think my reaction to that first trembling moment paved the way for Troubadour. I do okay one on one, or even with a people, but if you put me in a venue with hundreds of people I come undone. Just can’t do it, if you know what I mean. It’s not stage fright…it’s stage catatonia.

Anyway, some time in junior high a bunch of really hip kids decided to form a band. Mind you, these guys were like twelve years old and had never played an instrument in their lives, but two of them got electric guitars for Christmas and started banging out the four-chord progression of Louie-Louie, while one of them got a massive Ludwig drum set – because that’s what Ringo was using, don’t you know – and they needed someone who could play bass. Well, I could. I was playing both the acoustic bass and guitar by that point, and my grandfather had a massive pipe organ in his house that I had been playing for years, so I had that one under my belt by then too.

At any rate, they convinced me to join them and I guess you could say I taught them how to play their instruments over the next year. One of the kids, Pete, was a soulful guy who liked writing poetry and was getting decent on the drums, and he started putting lyrics to the music in his head and he’d share his musings with us and somehow real music started taking shape.

I looked back on those first compositions of ours as something really special, the wonder of coming of age condensed into two and a half minutes of pre-pubescent wailings about acne and nocturnal emissions. We were twelve, you see, yet even then sex had become the center of our existence, and we were pegged to play at our school’s Spring Dance the last weekend of our last year there. We had a couple of our own pieces to play but by and large we were set to grind out a bunch of Beatles and Stones songs, with me doing double duty on bass and keyboards.

I was, of course, terrified.

Not only were there several hundred people at that dance, I knew each and every one of them. I had chewed my fingernails down to bleeding stumps by the time we were set to take the stage, and I found that the only way I could play was to turn my back to the dance floor – so I did. For two hours I rocked and rolled and I didn’t have the slightest idea anyone else was out there, and when it was finally all over with I packed my stuff and went home – and vowed I’d never do anything like that ever again.

We were, of course, invited to participate in a local ‘battle of the bands’ contest to be held in early July, and we needed two songs of our own in order to be contestants so were turned Pete’s composition into something really special while I cobbled together something generic and altogether bland for our second entry and we practiced and practiced until we were blue in the face – then it was time to set up our instruments on what was indeed a really BIG stage.

“How many people are going to be here?” I asked one of the promoters.

“Oh, last year we had almost two thousand, but we’ve sold five thousand tickets so far…”

My knees were knocking by the time they announced us, but I turned the organ so I faced away from the lights and we launched into Pete’s soliloquy – a soothing, polished love song that just sounded silly when five twelve year olds sang it, but the girls out there loved it and they went wild.

Then we slipped right into ‘Lucy-Goosey’ – my hastily contrived fluff piece, and we brought down the house. We won, too. The contest, and we picked up a recording contract – with Lucy on the A side and Pete’s soliloquy on the flip side. The 45 sold a half million copies before we were in high school and as I was the songwriter listed on Lucy the lions share came to me.

And that was the end of that.

I haven’t mentioned my parents because, well, they died when I was young, like three years old. An airplane crash, a jetliner taking off from Mexico City, and really, I haven’t the slightest memory of either of them. I lived with my father’s father and his second wife, and I grew up in Beverly Hills. They were show business types, he a producer and she an actress of some repute, and I grew up around Hollywood types, lots of famous people I guess you could say, but my upbringing left me with a different sense of proportion. If people saw glamorous stars and western heroes, I saw sullen, moody drunks sitting by the pool out back – all fawning over my ‘grandmother’s’ legs. I mention all this only to add context to the sudden fame thrust on me after Lucy-Goosey went platinum later that summer.

I for my part, decided to concentrate on my classical compositions after that, which pissed a whole lot of people off, but I did all through high school and into college, and by that time what fame the song generated had all but slipped away – and I was grateful, because I considered the piece pure garbage.

So I went to Stanford unencumbered by that baggage, and studied composition and philosophy with no ends in mind – until a friend asked me to join a group he was putting together and it became more widely known that I had penned Lucy, once upon a time.

“I always wondered what happened to you,” Deni Dalton said, and that’s how we met, Deni and I. She had this smokey voice that seemed to seethe dark sexuality, and when she looked you in the eye I felt like a banana being peeled in the monkey house. Whatever protective layers I had on that day, say that look of smug condescension I liked to slip on from time to time, she cut through that crap like a hot scalpel through bloody fat. She was Music. She was bigger than life. I was in love, but then again everyone who laid eyes on her fell in love. She always wore black, too. Black hair and black eyes, heavy black makeup – she was Goth before there was such a thing.

And she had kind of a black heart, too. Mercenary, I guess. Not educated yet smart. She read people like others read books, and she had a nose for money, was always looking for the angle that would lead to fame and fortune. I think she took one look at me and saw her opening.

“Your Dad still with Universal?” she asked.

“My father died when I was three.”

“Aaron Dorsin? He’s not your pops?”

“My grandfather.”

“Oh, right. He’s still with Universal, ain’t he?”

“Last I heard.”

“Well, we’re looking for someone new on keys, and Luke says we should give a listen. So, I’m listening.”

We were in the living room of this run down three story house in Berkeley, and all there was in the room, besides a dozen or so people on a u-shaped sofa, was an old upright piano – and then one of the girls on the sofa went down on the guy sitting next to her.

So…I looked at her for a moment and started playing to her rhythm, then Deni caught where I was and she stood and started swaying to the music coming from the girl’s mouth. I was drifting between Bartok and Dave Evans until she hit the short strokes, then I just let the music flow for a while, a loose, swirling flow, and Deni came to me and kissed me for a long time, before she played a little music of her own.

And so began a very interesting time in my life. I like to think of it as my purple paisley patchouli period, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

+++++

It was a funky house, of that much I was certain. Channing Way was kind of an epicenter of seismic music in Berkeley for a few years back in the late sixties, and maybe Deni’s purple house was our ground zero. Her background was coffee house folk, kind of a dark California counterpoint to Paul Simon’s more upbeat New York vibe, and you might get that if irony is your thing. If Simon had inherited Gershwin, Deni had been mainlining Thelonius Monk for years – yet she felt like she was ready for bigger sounds. She wanted to create fat, epochal rock, anthems for a new generation already grown tired of Beatlemania. She didn’t want cool reflections, she wanted steamrollers and wrecking balls. Most of all, she didn’t want to play small clubs anymore. She wanted to hit college campuses and then, maybe, if she got lucky, move on to bigger and better things, but she saw rock and roll as a doorway, an entry into something really big and bold.

To me, as a keyboardist in 1968, big and bold meant synthesizers and mellotrons. Those two instruments, I surmised, might allow some of the more bombastic elements of classical forms to merge with the more simplistic forms of rock that seemed to be yearning for bombast – and like every other classically trained musician on the planet I realized Sgt Peppers had shown us the way to the door, while Pet Sounds had given us the courage to break on through to the other side. Martin and the Beatles began introducing classical motifs on Sgt Peppers, but it was Fixing A Hole that caught fire in Deni’s mind. The Beatles married the baroque to old English choral music and it was brilliant, but it wasn’t American. The Beatles were a Jaguar XK-E, something restrained and elegant, gorgeous yet full of unrealized potential; what Deni wanted a Shelby Cobra with glowing pipes, something untamed and unleashed, music that would overpower the soul and make people scream when elation overpowered sensibility.

She had cred in the music business, but not a lot, not the kind I’d had, anyway – but what I did have was my grandfather. He was fairly high up on the food chain at Universal, and their MCA Records division wanted to cash in on the exploding pop/rock business. We retreated into the house on Channing Way one February day and didn’t come out again until May, and three of us hopped in someone’s old VW Microbus and tooled down the 101 to Burbank and went to my grandfather’s office.

He was old then, seriously old, but he was also sharp as a tack. We walked in and he looked at us like we’d just crawled out from under a rock, which, I have to say wasn’t far from the truth.

“Aaron,” he asked when he quasi-recognized me, “is that you under there?”

You see, by 1968 my hair was hanging down somewhere south of my knees, and George Harrison’s beard had nothing on mine.

“Hey Pops,” I said, ‘Pops’ being my characteristic greeting. “We need a recording studio. I want to cut an album.”

I am not, you understand, one to waste time on idle chit-chat.

“Oh?” he said, with one raised eyebrow.

One eyebrow meant he was listening. Two meant you needed to start running for the door.

So I tossed our demo down on his desk, a big Tascam reel-to-reel spool, and he looked at it, then at Deni. And you have to understand this about Pops: he was only interested in her by this point. If she could sing, great, but she had great tits and I could see that working over in his mind – as in: she’ll look great on an album cover. He had no interest in her physically, only in the commercial appeal of Deni’s tits.

So he picks up his phone and dials an extension.

“Lou? Aaron’s here, and he has a demo. Can I send him up now?”

So off we went, off to see the wizard. A dozen people gathered and listened to our demo and we walked out an hour later with a recording contract. We hopped in the VW and drove back up the 101 in a blinding rainstorm, got back to the purple house a little after midnight – and Deni attacked me then. In a good way, if you know what I mean. We came up for air a few days later and the really interesting thing about that time is we both realized we were like heroin to one another. We were dangerously intoxicated when we mixed, so much so we knew we were in danger of losing ourselves, each to the other.

After those two days and nights together Deni dropped the whole Black Goth thing and went in for this deep purple paisley look. Flowing silk capes of purple, and the house began to reek of patchouli. Patchouli incense was burning 24/7, and she put patchouli oil in everything, notably the polish she used to wipe down her rosewood furniture. The scent wasn’t quite overpowering, but it was close, and the whole patchouli thing became indelibly linked to those months. I can’t not think of her when I run across that scent.

Anyway, we loaded up all our gear and ambled back to Burbank a week later, and we had several days booked to get the sound we wanted down on tape. I’ve since read books on musicians of that era, these being little more than monographs of artistic egoism run amok, and I shudder to think what would have happened to us if that had been the case. Instead, it seemed as if Deni and her mates knew this was their one big shot, and they had to get the job done this time or prepare to wait tables for the rest of their lives. We came together, in other words, and the results were something else.

We ended up spending a month in the studio, yet before we were finished MCA released a single that shot up the charts into the top-10, and on the strength of that alone they booked us to play three nights at the Universal Amphitheater later that summer – and I didn’t think anything about it at the time, maybe because I was so wrapped up in the moment.

Deni was a lyricist, a good one too, but she wasn’t quite what I’d have called an original. She listened to other recording artists all the time, listening for inspiration and ideas. New ways to spin a phrase, new transitions between parts of a song – yet she couldn’t read or write music, what’s called notation. She had an instinctual grasp of the inherent musical order within a phrase, but she couldn’t see structure when expressed in notes and chords. This wasn’t a big deal as I looked at the innate phrasing of her lyrical constructs and went from there, and as she wrote stuff she’d come and sing variations to me. Not a big deal, and most pop music is created that way these days, but it was a big move away from the classical paradigm – where arias were derived from the inherent structure within a passage of music.

An unknown named Elton John showed up while we were in the studio and he dropped by, listened for a while then disappeared, and I dropped by one of his sessions a few days later and was blown away by his exuberance, his showmanship – even in the studio. And it hit me then, my lump on a log stage mannerism. I was not and would never be an Elton John. He was an impressionist masterpiece, and I was a Dutch still life, destined to reside on the edge of the stage, the edge of the world, my back to the action – and I knew there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. As soon as the lights went up I began to freeze inside, like my mind was suddenly and completely encased in brittle ice.

So, the album was released and it was a bigger hit than even Pops thought it would be. And yes, there was lots of cleavage on the front cover. Purple paisley and cleavage. We played a few small gigs on Sunset and Hollywood, a few parties in the Hills of Beverly too, and we started mapping out our second album during that time, too. Then our first night at the Amphitheater came up and everything inside just kind of snapped. I couldn’t even walk out on stage for our practice session that afternoon, and for the first time what had been kind of a modest idiosyncrasy turned into a real liability. I looked at my mates looking at me and I knew they couldn’t understand…hell, I didn’t understand…but this was something that could seriously fuck up their chances of making it big.

Pops called a doc, some Beverly Hills shrink, and she came out and gave me a shot in the hip, told me to rest for a half hour, and she went with me and we talked.

She looked like Faye Dunaway, if you know who I mean. About fifty, blond hair and seriously gorgeous. Smart? Dear God. It was like she had this ability to look inside souls, take an inventory and figure out what was wrong. Me? It was all about losing my parents when I was a kid. My dad was an actor and he had gone down to Mexico, to Acapulco, to receive some kind of award, and their plane crashed on the way back, so yeah, separation anxiety lead to more and more anxieties and Pops had no idea. Hell, neither did I. Anyway, understanding did not lead to catharsis and by the time showtime rolled around I was no better but the docs magic potion helped me keep it together long enough to do the show, and while it was magic, the ovations and the wild applause, as I walked offstage I passed right out. Down like a sack of potatoes, still on stage.

Or so I read in newspaper accounts the next morning. Despite not having diabetes the episode was ascribed to hypoglycemia and that was that. I spend all day working with a studio musician who would be on standby, a kind of understudy, in case I cratered that night – and of course I did.

I watched from backstage as this stranger played my music, and in fact he played better than I had, a supple fact not lost on Deni and my bandmates. I didn’t even show up for the third night’s performance, and when we returned to Berkeley the next day everyone tried to not make a big deal about it – but I knew something had changed between us. We all did, Deni most of all. I felt like damaged goods, a broken doll that not even all the king’s men could glue back together, but we started writing music again and pretty soon all was forgotten.

We went back to Burbank a few months later and started laying down tracks when word came that we were going to tour North America in the fall and Europe the coming winter and I started going to the shrink in Beverly Hills. Maybe she could help me, I told my mates. Yeah, maybe, they said.

Then a funny thing happened. The shrink invited me to go sailing with some friends of hers the next morning. I accepted the invitation, too, if only because I wanted to get to know her better, and I ran out and got a haircut too. Bought some boat shoes, of all things, and some natty red sailing shorts to go with them.

The boat, a huge racing yacht that had been famous in the 30s, belonged to her husband, of course, a billionaire property developer who owned half of LA, and they had a professional crew sailing the boat so all I had to do was sit around and look interested in my boat shoes, but the truth of the matter was I did indeed find myself interested. In fact, the idea of sailing away from all my anxiety seemed very enticing. I talked to the skipper about boats and sailing for a few hours and I learned a lot that afternoon.

There was another couple on the boat that day, a property developer from Newport Beach who had brought his wife and daughter along. The girl was maybe two years younger than I, and she was studying some kind of psychology at UC Irvine. And she loved our album. Her name was, of course, Jennifer. Every other girl in OC is named Jennifer, has been since the beginning of time.

She looked like one of Southern California’s home grown Hitler Youth so common to Orange County back in the day: rich, privileged, blond haired and blue eyed, yet she was sweet – and she loved sailing. Well, I thought I might love sailing too so we had something in common, right? Anyway, we talked boats and I figured out pretty quick she knew a lot more about boats than I ever would, that she’d grown up around boats, and also that she really, really liked our first album. She even had an original 45 of Lucy-Goosey, bless her heart, and we went out for a burger after we got back to the marina, then I drove her down to Newport, to her dorm at UCI, but when we got there she pointed me towards the beach and we went down to the peninsula, watched the moon fall on Catalina just before the sun decided to show up for a return engagement.

There was a boat show in Newport, she told me, usually in April or May, and she wanted to know if I’d come down and go to it with her. I said ‘sure, sounds fun’ before I knew what had happened, and we looked at one another when I dropped her off at the dorm like we were not quite sure where this was going. I wanted to kiss her, and I could tell she wanted me to, but I couldn’t – because I was afraid, and I told her so, too. I told her about seeing the shrink, about my looming performance anxiety and she seemed to understand. Anyway, I gave her my number at Pop’s house and she leaned over and kissed me once, gently, then again, not so gently, and then she told me I didn’t have anything to be worried about where she was concerned and everything kind of slipped into place after that. Right there in the car, as a matter of fact.

We finished the second album over the next few weeks then took a break, our first big tour not scheduled to begin for a month or so, and I went to Pop’s house to unwind. Everything seemed pretty much the same there, except Pops seemed to be slowing down, and suddenly, too. He said his back hurt more than it had recently I talked him into going to see his doc.

And Jennifer called my first night there, said she was going to be at the marina Saturday and wanted to know if I wanted to go out on a new boat. Sure, I said, and we set a time to meet up – and after that I couldn’t think about anything other than her – until my next appointment with the shrink, anyway. Pop’s internist was in the same building as mine so I dropped him off for his appointment then ducked in for mine, but when I came back for him he was still inside so I sat and waited.

And waited.

And a nurse came out and asked for me, led me back to an office – where I found Pops all red-eyed and an old internist handing him tissues. Prostate cancer, advanced well into the spine was the preliminary diagnosis, but biopsies would be done early Monday morning and we’d go from there. We left and he was pissed off because the same doc had told him a year ago the pain was probably related to a fall he’d taken a few years before. Maybe if he’d been more thorough he’d have a chance, he said, because if it had moved into the spine that was it.

“That was it?”

I understand my parents died when I was three, but since then no one I knew had kicked the bucket – and now, all of a sudden, the most important person in my life was telling me he was going to die, soon? That this was it?

I had an emotional disconnect about that time, I guess you might say. I was a little more concerned with my well being than his in that moment, a little more than afraid. No, let me rephrase that. I fell apart and we held on to one another there in the lobby for way too long, then we walked over to Nate ‘n Al’s for bagels and lox. He called some of his buddies from the studio, told them to come over for a few hands of poker – which was code for ‘shit has hit the fan’ and we sat there watching the ice melt in our glasses of iced tea, neither of us knowing what the hell to say to one another. My grandmother, his wife, would surely come apart at the seams tonight, he said, then this lanky gentleman walks in and comes over to our booth and sits down next to me.

Jimmy Stewart, in town between shoots and an old friend of the family, looked at Pops and sighed. “Aaron, you look just awful. Now tell me, what’s going on here?”

So Pops lays it out there and then Jimmy is all upset, the ice in his iced tea is melting along with ours, then he finally turns and looks at me.

“Heard that album of yours. It sure isn’t Benny Goodman, is it?”

Pops broke out laughing at that. “It sure isn’t, but that lead singer of theirs sure has great gonzagas. World class, if you know what I mean.”

Stewart rolled his eyes, shook his head. “All he can think about at a time like this is tits. Aaron? You’ll never change.”

“Amen to that, brother,” Pops said. “What do you have in that sack, Jimmy? Another model airplane?”

“Yup, yup. Me and Henry, you know how that goes?”

“Did you ever see his model room, Aaron?” Pops asked me.

“Yessir, been a few years, but…”

“I was building that B-52, wasn’t I?” Jimmy recalled. “Wingspan this big,” he said, holding his hands about a mile apart and we all laughed. He got up and patted Pops on the shoulder a minute later, told him he’d call soon, then he ambled over to a table where Gloria was already waiting and I could see the expression on her face.

I got up early and drove down to the marina, met Jennifer at the anointed hour and she took me down to a slip below an apartment building and hopped aboard a brand new Swan 4o. There were two other girls onboard already and they slipped the lines, let Jennifer back the boat out of the slip while they readied the sails. We sailed out of the marina after that, then turned south for Palos Verdes – and with barely enough wind to fill the sails the girls soon gave up and turned the engine on. Seems they were delivering the boat from the marina to it’s new owner down at the LA Yacht Club and I was along for the ride, and by the time we cleared the Point Vicente lighthouse we had enough wind to raise sail again and had a rip-roaring nine mile sleigh ride after that.

That was difference between 40 feet and 83. The smaller boat felt almost alive compared to the old J-class boat I’d sailed on the week before, and I found myself mesmerized by the sensation. I didn’t know it at the time, but Jennifer studied my face that day, told me once she was reliving her earliest sailing experiences by watching my reactions that day. She was very dialed into me, I guess you could say, even then.

We turned the boat over to her new owner and drove down to Newport, stopped and had an early dinner at The Crab Cooker, and after we dropped off the girls she drove me back up to the marina, and I told her about Pops then, about what my grandfather really meant to me, and she remained quiet all the while, let me ramble until we pulled into the lot where I’d left my car. She parked and turned to face me, leaned the side of her face on the seat and stared at me.

“What are you going to do now?” she asked. “Try to go on tour?”

“I don’t think I can do that. I need to be here now.”

She nodded her head. “I think so, too. You need anyone to talk to, just call me. Any time, day or night. Got it?”

I nodded my head, then looked her in the eye. “What happens if I fall in love with you?”

“If?” she said, grinning.

“Okay. When I fall in love with you?”

“Are you sure you haven’t already?”

I can still feel that moment. Like it was the most important moment of my life, those precious seconds are still right there with me, wherever I go.

“I know exactly when I fell in love with you,” I said.

“Oh?”

“About a minute ago. Before that I was fighting it.”

“I know.”

“You know?”

“I think you’ve been fighting it all day. I know I have.”

“You want to go meet my Pops?”

She nodded her head. “Yeah. I think that’d be a good thing?”

So we went. She met Pops and he loved her too, which was kind of a good thing. It was the first time I’d ever come home with a girl, and the moment wasn’t lost on either of us. My grandmother was a little coy about the whole thing, a little too reserved one minute then effusive the next, but by the time we left she’d come around too.

“So, you’re the one?” Pops asked when he walked us to the driveway out front, and Jennifer didn’t know what to say just then, but I did.

“Yeah, Pops, she’s it. You mind if we run off to Vegas and do the deed, or did you want us to do it here?”

“Let’s all go to Vegas,” he said. “I can hit the tables after, and who knows, maybe I’ll get lucky,” he added, popping my grandmother lightly on her tail-feathers.

And we all laughed at that, even my grandmother, but we weren’t fooling anyone. Not by a long shot.

“He’s kind of cool,” Jennifer said as we drove back to the marina. “Old school, I guess.”

“He is that. Not many like him left in this town.”

“Thanks for letting me meet him. Even if you were joking…”

And I looked at her just then, like maybe I’d been joking, and maybe I hadn’t. And she looked at me, too.

“You were joking, weren’t you?”

“We’ve known each other a week,” I said. “Maybe it would be nuts, but I haven’t been able to think about anything but you for days.”

And she nodded her head, looked down and didn’t say a word.

“What about you,” I asked. “Am I too late? Already spoken for?”

“I was serious about a guy in high school, and we kept dating after, even after I went to Stockton and he went to SC. We broke up six months ago, well, at Christmas.”

“What happened?”

“He met a girl, I guess. ‘Someone better’ was the way he put it.”

“Jeez. That was nice.”

“Yeah, you could put it that way.”

“No one since?”

She shook her head. “It messed with my head pretty bad. We’re seeing the same shrink, you know?”

No, I didn’t, but it kind of made since now so I nodded my head. “What happened?” I asked.

“Pills. My roommate found me in time, got me to the ER. Pumped my stomach, that scene. I came home after that. Haven’t been back, really.”

“You going to finish your degree?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Anything else you want to do?”

“I like sailing, that’s about all though. Dad put up some money to get a sailboat maker up and running, and I’m going to start working in the marketing and sales department this summer. I guess we’ll see how it goes.”

“Sounds kind of fun. Not a lot of stress, anyway, and doing something you love.”

“What about you? You going to keep playing?”

“Composing, anyway, and working on the studio tracks. We have a studio musician who’s preparing to go out on the road if I can’t handle our next concert.”

“Where’s it going to be?”

“San Francisco, at the Fillmore. Hendrix is going to be there, some Brits, too. Should be a scene.”

“Wow…”

“You wanna come up?”

“You sure you want me to?”

“You know, we were talking about getting married a few minutes ago. Nothing’s changed.”

She looked at me again and I could see it all over her face, in her eyes. Not quite shame, but a real close cousin. Something deeper than embarrassed, anyway. Trying to kill yourself – and failing – had to be hard to deal with by yourself, but to lay it all out there like she just had? She either had guts or she wanted to see how real I was. The thing is, I wasn’t running. I think I started to really fall for her after that. I mean a deep kind of falling in love, like I wanted to take care of her. I know that seems a little off, but when I saw her vulnerabilities I wanted to be stronger so I could help her carry the load.

And I think that was a turning point for me.

Anyway, when we made it to her car we got out and walked around the marina for a while, looked at boats and talked about sailing – and I held her hand all the while. The thought I’d let go of her in a minute or two, let her drive back to Newport without me was hitting home real hard, a lot harder than I expected, and I stopped in front of a hotel there, turned her into my arms and I just held onto her. Maybe like forever, if you know what I mean, then I kissed her, told her that I loved her and maybe we should go get a room.

I remember those eyes of hers. Looking up at me then, so full of lingering intensity. She was so insanely gorgeous, too, probably the most beautiful girl I’d ever known, and if that asshole hadn’t fucked her up she would have been okay – or at least I kept telling myself that over the years. And hell, who knows, maybe I believed it, too, but she was fragile after that breakdown. Always was, right up to the day she left me.

+++++

I drove up to Berkeley a few days later; it was time to start rehearsing for the Fillmore gig. That ‘feeling stronger’ vibe stuck with me, too, and I felt good about going out on stage for the first time in my life. Deni picked up on the vibe, and she was ecstatic about the whole Jennifer thing, too. Rehearsals went great and I picked Jennie up the night before we were set to play, and we went down in time to listen to The Nice. There weren’t many of us trying to bring new technology onstage, and while Keith Emerson was creating quite a storm on stage everyone was hanging around in this haze of expectation, waiting for Hendrix.

He was the current God du jour, but for any keyboardists watching that night Emerson was surreal. Here was someone, finally, bringing classical structure into rock, and while his rendering of Simon’s America was electric, what caught me was a piece called the Five Bridges Suite, which fused classical with jazz and rock. About halfway through that piece I started to look around at the crowd and a kind of swaying trance had taken hold. People didn’t want to dance now, they had been transported somewhere else, someplace deep within Music, deeper than I’d ever thought possible. Even Jennie said “wow!” when those guys wrapped up and drifted into the crowd…

But when finally Jimi came out and the place erupted, and when The Experience started in with Fire you could understand what the electricity was all about. I hung on til they finished up with The Wind Cries Mary, and when I looked around the place I could feel something else passing through the crowd, something hard to put my finger on, but what struck me was the power music held over the crowd. Something awesome and huge, some force I’d never reckoned with before, and what got to me right then was Emerson. He was watching the crowd too, gauging the sudden surge of empathy, and I guess like me he was lost inside the wonder of the moment.

Another thing that hit me just then: the amount of pot hanging in the air. From fifty feet back the air was literally a purple haze, and with the multi-colored stage lights bathing the area around Hendrix the atmosphere was otherworldly. I knew a couple of cops were working the back of the crowd, but I wouldn’t have wanted to be them in this place. After the ‘free-speech’ demonstrations across the bay over the last few months, their was another ‘something’ hanging in the air, apparent, and it weren’t purdy, if you know what I mean. And that vibe was the raw underbelly of music at the Fillmore…

Sure, a lot of the music was about ‘peace and love’ but there was an awful lot of anger in the air; even so there was this Hell’s Angels vibe too, an undercurrent of outlaw malevolence that felt rooted in the desire to burn everything down to the ground. That was San Francisco then and I suspect it’s always been that way. Like some people working the fringes wanted to create something new, but to me it felt like this Fillmore fringe didn’t really care who got burned along the way. So, yeah, I think there was real anarchy in this group, like this new fringe wanted their parent’s world to dissolve within the purple haze hanging over that crowd inside the Fillmore, all emotion rooted in infantile rebellion, the tantrums of spoiled children.

Yet sometimes children are right, too.

That was in the air, too. Even the music. Our parent’s forms and structures, subverted and inverted, creating something new, anarchic and inclusive. Like the Beatles opened the doors to polite society and now the riffraff was rushing in – burning babies in Electric Ladyland. Music was, right before our eyes, becoming more political than it had in a hundred years, when Wagner politicized opera in post-Napoleonic Europe. If you think that’s trivial stuff, just consider for a moment that Marx grew out of that music, and so did Darwin.

So yeah, something was stirring in the underbelly of that crowd. Something big and noisy, and maybe ugly, too.

+++++

We were the first gig of the night, so we set up early and I looked around the place while I helped hook up the Moog and Mellotron. The air clear now, the room didn’t look all that big, like a place full of magic. Just a room, I thought, not unlike many others around this city, yet I had felt those forces last night. Emerson had too. We talked after Hendrix left, talked about the vibe we’d seen and felt, and we talked in epochal terms about music shape-shifting to the needs of the moment. About the politics of music. We talked Nixon and Vietnam and John Wayne and about the image of a girl who had put a flower down the barrel of a National Guardsman’s rifle. Everything was linked, he said, but the links weren’t easy to see – not yet, anyway. Music had to become the fabric that joined all these disparate factions, and musicians had to claim their place as leaders of this movement. Heady stuff, and even Jenn seemed caught up in the moment.

Yet standing up there on that stage looking out over that empty room it was hard to see music as anything other than a diversion. Maybe we were the sideshow to the real action. I’d just read Jerry Rubin’s ‘Do It!’ – a real anarchist’s manifesto – and I wondered: could music take on that weight, shoulder that burden? Or would music fragment the way society seemed to be fragmenting?

Even when I worked with Deni it was there – this impulse to fly apart, to head off in uncharted new directions. There wasn’t some unseen political hand pushing us towards a grand unified theory of musicians leading a movement. Most of the kids on stage were just that: they liked to play the guitar or the keys. We got off on making music together, and I can’t recall ever sitting around and saying “Wow, did you see those riots up on campus today! We got to write about that!”

Yeah, but there was one anthem out there that contradicts all that. For What It’s Worth, by the Buffalo Springfield – and maybe that’s the vibe Emerson was channeling that night in the haze – but the idea hit me then that I had always seen music as a reflection of events, not a means to change things, but maybe it could be both and I’d never really seen it as such – and I had an idea.

I hadn’t played Lucy-Goosey in years. The music had dissolved into that early Beatles-like haze of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and She Loves You, Yeah-Yeah-Yeah, but it was still there, buried somewhere in our collective unconscious – so what if we…

Deni was kind of entranced by the whole thing, too, and she came up with a few bridges to make the pop refrains relevant once again. Lucy was going to go from bubble-gum chewing sycophant to radical anarchist on stage tonight, and the whole thing was taking shape in a burst of creativity that had come out of nowhere, man.

When the lights went down a slide was projected on the wall behind the stage, an image of that girl sticking a daisy down the barrel of the guardsman’s rifle, and I walked out and got behind the keyboards – then turned and looked at Jennifer standing in the shadows backstage and I smiled, then turned to face the sea of faces and raised my fist, then the room went black – with just a small spot on me, and that image of the girl hanging back there behind the purple haze.

I started with the simplest piano refrains from Lucy-Goosey and the sea of faces went silent as quiet expectation replaced hyped anticipation, and my piano was almost in chopsticks mode: simple notes even a child could play, awakening memory. Our lead guitar stepped out and another spot hit him, and he started echoing my simplistic melody. Deni came out next and the crowd erupted, then as quickly shut down as she started into an even simpler, quieter version of my original lyric, and she turned to a small harp and echoed my notes as the lights faded, leaving only the image of the girl – which soon faded to black as my piano grew softer, then silent. In the darkness the rest of the band came out and when the lights flared we turned Lucy into a molotov cocktail throwing radical with what I’d say presaged a grungy-heavy metal infused sound – music that no one in the audience had heard before – and the surge of energy was cataclysmic. I kept the simple piano melody going, but that was echoed by soaring, dark chords on the Mellotron, and with Deni’s inverted lyrics Lucy’s transformation was complete.

And I felt that transformation in my soul, too, like I’d just grown up. The insecure teenager died out there that night, and when we walked offstage an hour later I walked into Jennifer’s arms and held on tight, because I knew the ride was about to get real bumpy.

+++++

Pops was a lot sicker than he let on, and he kept everything wrapped up and put away, out of sight. Every time I called he was ‘fine, doing great’ – and Terry, his wife, my ‘grandmother’ went along with his charades, and it worked ‘til we came to LA to play several concerts around town. I went home after our first and when I saw him I burst out crying. I couldn’t help it.

“Do I look that bad?” he asked.

He looked like an orange scarecrow, only worse.

“The color,” he said, “is from liver failure. I kind of like it, too. Like a walking traffic sign, don’t you think? When I walk out of the doctor’s office everyone stops and stares.”

I felt sick, too, just looking at him, and then Terry told me he had maybe a month or two left, and I kind of fractured when I heard that. Like I didn’t know what to think. Pops was my last link to an almost invisible past, and without him I would be well and truly alone. There weren’t any brothers or sisters or aunts and uncles, there was just me and Pops. I was going to be, if I remained alone and childless, the last of the line.

And that was a big question hanging in the air between us.

What’s with Jennifer, he wanted to know.

“We’re good,” I said, but there was something else hanging in the air. That whole fragile thing. She was depressed, and when she started going down that hole she turned to dolls to pick her back up. Dolls, as in The Valley of The. Pills, in other words, and here I need to digress a little. I didn’t do pills. I didn’t smoke – anything. I didn’t drink much, because I didn’t like the whole idea of losing control. I know, like the idea we have some kind of control is an almost comic idea, but the point is we do have the ability to control some things, and losing what little I had was to me a Very Bad Thing. I tripped all I wanted when I disappeared inside my music, but I could come out of it intact and lucid. I had Deni disappear down the LSD rabbit hole and not come out for days, and that scared the shit out of me. We’d been through two lead guitarists over the course of a year simply because one drug or another had taken them someplace they just couldn’t break free of, and I wasn’t going there.

So when I saw Jennifer headed down the same road I told her it worried me, and she told me to fuck off. So I did. I put her on a plane back to her father and told him what was going down, and what I heard back from him wasn’t worth mentioning, but he’d thought he was done with her and wasn’t happy to have her back under his roof.

I started spending more and more time in LA, spending as much time with Pops as I could, and my understudy started filling in more often when he started the terminal decline. We were in Cleveland when Terry called me, told me to come home, and it was about five hours before the show that night when I called Deni and told her. She came to my hotel room and we talked, and she told me to take my time, that they’d manage without me and I held her for the longest time. We’d been together as a group for more than two years by then, and I realized she was about the closest thing to family I’d have left – and I told her so.

“I never wanted you to be my brother, Aaron,” she told me. “All I know is we work well together, like I always imagined a husband would be, ya know?”

“That day, you remember?”

“Yeah. Love heroin. I’ll never forget. I’ve never loved anyone like I loved you,” she sighed, and then she was crying. “God, I don’t want you to go. Something’s going to happen to you back there. Something fuckin’ big’s coming, and I feel like it’s going to crush you, man.”

“I don’t know what I’m going to do without him, Den. I’m scared, and with Jenn gone? I don’t know, man, I don’t know…”

“I’m here. Don’t you forget that.” She looked at me and we kissed, I mean like the last time we kissed, and I was full of these bizarre electric charges flicking off like lightning all over my skin, then she looked at me again. “I love you, and I will forever” she sighed, then we kissed again, and this time we were hovering beyond the abyss, ready to fall into bed, but she pulled back and ran from the room.

I got my bags together and made it out to the airport in time to catch a one-stop to LAX, and made it to the house a little after midnight. I went to Pop’s room and we sat and got caught up while Terry left to put on tea, but she came back in a few minutes later, her eyes full of grief. She turned on the TV and there were news reports of an airplane crash, a flight from Cleveland to Buffalo, and a hundred and fifteen people, including all members of the group Electric Karma, were feared dead.

I blinked, recoiled from the very idea Deni and all my mates were gone, that the sum total of our existence had been wiped from the slate in the blink of an eye, but the pictures on the screen told a very different story. A midair collision about a mile out over Lake Erie, and the 707 had burst into flames and fluttered down to the water, then slipped beneath black water.

Pops died the next day.

+++++

Jennifer thought I died that night and she came undone. Razor blades this time, and she’d meant to take herself out, no doubt about it. By the time I called their house the next morning the damage was done, though I didn’t find out for a few more hours. When I talked to her father later that day he sounded relieved and furious, and I told him I’d be down as soon I could. He said he understood and we left it at that, and Pops slipped into a morphine induced coma later that afternoon. We didn’t say goodbye, but when I held his hand I could feel him respond to my words. When I told him he meant the world to me, and that I’d miss him most of all he squeezed my hand, and I could hear him talking to me. All the talks we’d had over the years were still right there, and Terry was with me, holding on to me, when he slipped away.

She was English. Had had a good run in Hollywood after the war, made a half dozen romantic comedies with the likes of Cary Grant and, yes, Jimmy Stewart, so when Pops moved on it was a big deal in Hollywood circles, yet the death of my bandmates cast a long shadow over the whole affair. Everyone knew about Pops and me, how tight we were, yet Terry was big surprise – to me. I’d never really appreciated how close they were too, but one look at her and you knew it wasn’t an act. She stopped eating for a month, literally, and wasted away to nothing – and then I had to admit I really felt something for the woman. She wasn’t just Pop’s third wife, she too became the one last link I had to him, one I’d never realized existed, and all of a sudden I was scared she might die too.

And let’s not forget Jennifer, lying, in restraints, in a psychiatric hospital tucked deep inside the hills above Laguna Beach. I started driving down to Laguna every other day, then every morning, and I spent hours with Jennifer then drove back up to Beverly Hills, back to Pop’s house, and I tried to get Terry out of her funk.

About three weeks into this routine I decided to take Terry with me down to Laguna, try to get Terry to see what the real contours of falling into depression looked like, and it worked. That day marked a big turnaround for all of us, because she reached out to Jenn and they connected.

Like a lot of people around that time, I’d recently seen 2001: A Space Odyssey, and to me that time felt a lot like one of the key passages in the movie. When Hal goes bonkers and cuts Frank adrift, and Dave goes after his tumbling body in the pod – helmet-less. I wasn’t sure if I felt more like Dave, or Frank, but I knew everything was tumbling out of control and I was the only one who could set things straight.

Like Pops had set me straight after my parents died, I knew it was my turn at the controls, and I didn’t want to let either Pops or my old man down. Hell, by this point I didn’t want to let Jennifer’s father down. Whatever was wrong with Jenn, I saw then that her old man was probably behind a lot of it – so I’d in effect sent her back into the snake pit.

Nope. Not again. When you tell someone that you love them, you don’t do that. It’s a simple proposition, really. Either you mean what you say or what you say is meaningless, and now I took that to heart.

I loved Jenn. Simple as that. And I loved Terry, too. Simple as that.

So, let me tell you a little more about Terry.

She met Pops when he was in his late sixties. They got married when she was thirty three. She was forty four now, and every bit the Hollywood starlet she had been just a few years ago, and in the aftermath of her decision to rejoin the living she decided she was either going to move back to London and take up work on the stage, or make another movie. Maybe a bunch of movies.

And she wanted to know how I felt about her moving back to London. Specifically, did I want to her remain in LA, remain a part of my life, or did I want her to move on.

Mind you, I had just turned twenty seven so I wasn’t exactly a babe in the woods, and I’d never considered her my grandmother. She came into my life when I was sixteen, when she was considered one of the most desirable women in the world. Let’s just say I’d spent a few sleepless nights over her and leave it at that, and I think you’ll grasp the contours of my own little dilemma.

So, I told her ‘Hell no!’ I didn’t want her to just move on. I told her she was an important part of my life with Pops, and that she would always be important to me. The problem I didn’t quite wrap my head around is she didn’t see it that way. She’d spend ten plus years married to man who hadn’t been able to perform his marital duties for, well, a long time, and she was just entering her prime. The biggest part of the problem was the simplest, most elemental part, too. I still found her attractive, devastatingly so.

There was a part coming up, just being cast, where she’d get prime billing next to some very big names, and she’d gone to the audition dressed to kill. When she came back she was elated; she’d gotten the part and shooting began, in France, in three weeks. She wanted to celebrate and so we went down to The Bistro – where her landing the part was all the buzz. Everyone came by to congratulate her – and offer condolences – and everyone looked at me like ‘who the devil are you.’ Why, I’m her grandson – didn’t you know?

What followed was three of the most regrettably confusing weeks of my life, and I’ll spare you the details. Sex was not involved, thankfully, – or regrettably, depending on your point of view – but the whole thing was an emotional hurricane that left me drained. And Jenn began to pick up on the vibe, too.

“Are you sleeping with her?” she asked me one morning after I’d just walked into her room.

“What? With who?”

“Terry.”

“No.”

And I guess the way the word ‘no’ came out implied an air of finality, because she never brought it up again. And a few weeks after Terry left for Avignon Jennifer moved in with me, in Pop’s house.

Because he’d left it to me. He’d left everything to me, a not insubstantial sum of money. Then Electric Karma’s lawyers told me that as I was the only surviving band member, and there was no one higher up on the food chain in their world, all our royalties were now mine. In perpetuity. In other words, I was filthy rich, and all I’d done was write a few songs and nearly shit my pants in stage-fright a couple of times.

Herb Alpert was, literally, my next door neighbor and I talked him into a tour of the recording studio he’d just finished in his house and I decided then and there I was going to do the same thing, and a few weeks later architects and contractors were finalizing plans while contractors swarmed, then Jenn decided we needed to buy a sailboat.

So we went down to the Newport Boat Show and we looked at one yacht after another…Challengers and NorthStars and DownEast were a few of the names that stood out, but in the end I put money down on a Swan 41, a new Sparkman & Stephens design that had not even been officially launched yet, and wouldn’t, as it turned out, for three more years – which left us without a boat for the foreseeable future.

But there was a new company just starting up in Newport, called Westsail, and they had a 32 at the show that really struck a chord with me – and I bought her, right then and there, and after the show Jenn and I sailed her down to Little Balboa Island, to the dock in front of her father’s house. Pretty soon we were driving down there almost every day, taking Soliloquy out for a sail. We started hopping over to Catalina, dropping our anchor off the casino and snorkeling for so long our skin started to look like mottled white prunes.

Sailing kept me away from the house, and the construction project, but when that work wrapped I went to work on another project. I had all our master tapes delivered to the house and I got to work re-mastering the original cuts, adding some keyboard tracks I’d always wanted, then I took them over to MCA for a listen. They reissued both our albums, and I put together a gratuitous “Best Of Retrospective” just for good measure and before you could say ‘Money in the bank’ I’d banked so much money it was obscene.

So, I had a house in Beverly Hills, at least one sailboat in Newport Beach, more than ten million in banks everywhere from California to the Cayman Islands and a seriously crazy girlfriend who had an affinity for razor blades – and boats.

And with all my work done in the recording studio – it took all of six weeks, too – I was now out of things to do.

Ah, Terry. What about her, you ask?

Well, she had more money than God before she married Pops so that was never an issue, and I was soon reading about a secret marriage to her co-star in this new film, so presto, problem solved.

And within a week I was bored out of my mind.

“What about forming a new group?” Jenn asked.

And all I could see was Deni in that hotel room, telling me that she loved me, and that she always would.

“You know…I don’t think so. I can record an album myself if I really want to. I can play all the instruments, do everything but sing, and if I get the urge I’ll get someone to lay down a vocal track and do the rest on my own.”

She frowned, shook her head. “That’s not the point. Working with musicians on a common goal, that’s what you need right now.”

“No, it’s not.”

“Okay. What do you think about sailing to Hawaii?”

“What? You and me?”

“Yup.”

“That sounds fuckin’ bogus, man!”

Keep in mind, in 1972 ‘bogus’ meant something similar to ‘awesome’ these days. ‘Bogus,’ by the way, replaced ‘bitchin’ in the California lexicon, and ‘bitchin’ was a close cousin of ‘far out’ and ‘groovy.’ We clear now, Dude?

I had a million questions, the first being ‘could we do the trip on Soliloquy?’

“Fuck, yes. She was made for this kind of trip.”

“Oh?” Keep in mind about all I knew concerning sailboat was that the pointy end was supposed to go forward. Next, consider that Soliloquy had two pointy ends, so I was already confused.

“Yeah, we could hit Hawaii, then head south for Tahiti.”

“Tahiti?”

I’d heard of Tahiti. Once. I think.

“Sure. What do you think? Wanna try it?”

So, my suicidal girlfriend wanted to get me on a 32 foot long sailboat a thousand miles from the nearest land. To what end, I wondered?

“How long would it take to get to Hawaii?” I wanted to know.

“Depending on the wind, two to three weeks.”

“Weeks? Not months?”

“Yachts sailing in the Transpac Race do it in eight days. It’s not that big a deal.”

“Have you done it?”

“Twice.”

“Of course.”

“But this would be just you and me, no pressure. We could really get to know one another, I guess.”

“When?”

“Best time is June and July.”

“So…a month or so from now?”

“Yup.”

“Would you like to do this?”

“More than anything in the world.”

“Well, maybe we’d better get to work. My guess is Soliloquy isn’t geared up for this kind of thing.”

She looked at me and grinned. “I already have.”

“Ah.”

And so the worm turned.

+++++

I never considered myself a sailor. Never, as in ‘not once.’ I’d never been on a sailboat until the day my shrink invited me out on her husband’s J-boat, the day I met Jennifer, and yet I was hooked from that first day on. If you’ve ever looked at an eagle or a seagull and wondered what it’s like to bank free and easy on a breeze, well, sailing’s about as close as you’ll get in this life – and unless you happen to believe in reincarnation and hope to wind up as a bird in your next, that’s the end of that. Bottom line: after that day I began to consider myself a sailor – and I know that sounds ridiculous – until you consider sailing is a state of mind, not simple experience.

At that point sailing was, for me, heading out the Newport jetty around ten in the morning and dropping the anchor off Avalon 5-6 hours later. Soliloquy was a heavily built, very sound little ship and weather was never a factor; in forty knots with six to ten foot seas she just powered through the channel with kind of a ‘ho-hum’ feel, like – you’ll need to throw some heavier shit my way to make me work. She was confident feeling in bad weather, something I came to appreciate later that summer, but something I was, generally speaking, clueless about those first few months sailing with Jenn.

No GPS back in the day, too. Navigation was old school, and I bought a Plath sextant, a German made beauty, and Jenn taught me to use it so we shared navigation duties. I’d always been strong in math, and I guess that’s what carried me through music into composition, so sight reduction tables and the spherical trigonometry involved in celestial navigation wasn’t a stretch. Still, the first time we motored from Avalon to Newport in a pea-soup fog – and nailed it – I was proud of Jenn for being such an accomplished navigator – and teacher.

Anyway, we stocked the boat with provisions, including everything we’d need to bake bread at sea, and a few other necessities, like a life raft and a shitload of rum – because sailors only drink rum, right? – and I went to my favorite guitar dealer in Hollywood and picked up an small backpackers guitar, an acoustic beauty made in Vermont, and we were good to go.

We left Newport on the first of June, 1972, and we sailed to Avalon and baked bread that evening, and when the sun came up the next morning we pulled in the anchor and stowed it aft, then, once we cleared the southeast end of Catalina, we set a course of 260 degrees and settled in for the duration. Call it twenty-five hundred miles at an average of 125 miles per day, and though we racked off 150 most days, we had a few under a hundred, too. The stove and oven were propane, most lighting came from oil lamps, and we had an icebox – not refrigeration – so we went about a week with things like fresh meat and milk then switched over to canned goods and Parmalat milk for the next two. And the thing is, I found I just didn’t care. We figured out how to make things we liked using the things we had on hand, and we made rice and homemade curries that were something else – then you had to factor in the sunsets out there…a million miles from nowhere. Sitting in the cockpit with the aroma of freshly baked yeast bread coming out of the galley, and I played something new on the guitar while the sky went from yellow to orange to purple…well…yeah, it was magic.

One day the seas went flat, turned to an endless mirror, and the only things we saw all day were the fins of an occasional blue shark or United DC-8s overhead on their way to or from Honolulu, and I’d never felt so utterly at peace in all my life. We’d bought what we’d need to rig a cockpit awning so we did that day, if only to keep from being roasted alive under the sun, and I think we started in on each other by mid-morning, and kept at it through sunset. Like, literally, nonstop sex – for fifteen hours – and it was one of the most surreal days I’d ever experienced. Pure sex, cut off from everything else – not-one-other-distraction. Just intent, focused physicality.

I didn’t know Jennifer, not really, not before those hours, and I’m not sure she knew herself all that well, either, but we never looked at one another the same way after that. We were reduced to pure soul out there, not one false, pretentious emotion guided us. Soliloquy was hanging in that water, no wind stirred the sea and we’d drop a cedar bucket into the crystalline water and wash ourselves down from time to time, but other than that the day melted away – leaving pure love in it’s wake.

And that night the wind picked up, our speed too, then the wind really started blowing, the seas building and we sailed for three days under a double-reefed main and staysail, the steering handled by the Monitor wind-vane self-steering rig Jenn had installed by the factory. And still Soliloquy just powered through the seas, never once did we doubt her ability to carry us safely onward.

And a few windy days later the trip was over.

Jenn’s father had shown up a few days before our expected arrival and he’d secured a berth at Kewalo Basin, near the city center, and it turned out he was as excited as we were about the trip. The fact that it had turned out so peculiarly uneventful was icing on the cake…and because I think he had it fixed firmly in mind that the crossing would be something like making it to the summit of Everest he’d never considered making such a trip. Now he was on fire to do it, and was itching to make the trip back to California.

I wasn’t, however, not with him, and not on a 32 foot sailboat.

Yet Jennifer was. She thought it would be a good time for she and her father to mend some fences, and wanted me to come along.

And again, I didn’t want to be a part of that whole thing, and I let her know it in no uncertain terms. So, she told me to fly back, that she and her father would bring Soliloquy home to Newport.

Fine, says I, and I exit, stage right, on one of those United DC-8s we’d watched arcing across the sky. The thing is, there’s no easy way back from Hawaii to Southern California. Wind and currents make it much more doable if you arc north towards British Columbia, and then ride the current south past the Golden Gate to LA. It’s a much longer trip, and it takes a lot longer – as long as 4-5 weeks. Another drawback? You have to go much farther north, well into colder, arctic influenced waters where both storms and fog are the routine, so the trip is tough. More like the Everest expedition Jenn’s father didn’t want to experience, as a matter of fact.

So, a few days later I packed a bag and went to the airport. By myself. I flew to LA and took a taxi home, and like that it was over. The trip, our sudden affinity for each other – over and done with, like the whole thing had been a dream. Or a nightmare. It was like this thing she had going on with her father was a toxic, manic depressive beast where she had to convince herself she had to put things right, and fixing that busted relationship was a much higher priority that her relationship with me.

Jerry Garcia wanted me to help out on an album so I flew up north a few days after I got back, and we worked in the studio for almost a month, and by the time I left I had it in my head to do a solo album. Those sunsets came back to me then, playing that little backpackers guitar while Jenn baked bread down below, that sun-baked idyll, the buckets of seawater. I spent two weeks down in my basement studio laying down the tracks for just one song, and when I finished I carried it down to MCA and everyone who listened to it said it was the best thing I’d ever done. Could I carry through, create an album out of the experience?

Hell yes, I said.

And when I got home there was a message on my machine, from Jenn, in Victoria, on Vancouver Island. She and her did had had a gigantic falling out and he’d left her there; could I call her at the marina?

I called the number she left on the machine and some dockmaster ran down to Soliloquy to fetch her while my fingers drummed away on the kitchen counter, and when she finally got to the phone she was in breathless and in tears.

The whole trip had been a nightmare, she sobbed.

Was I surprised? No. As in, Hell No.

And when would she learn? How many more times would she let that mean-spirited asshole tear her apart. How many times would she run home and start the whole process all over again? What was I missing?

“What do you want, Jenn?”

“Could you fly up, help me bring Soliloquy back to LA?”

“Then what?”

“What do you mean?”

“Just that. What happens next?”

“We get on with our life. Together.”

“Really? Until the next time you need to run home to Daddy?”

“What do you mean?”

“Maybe you two were meant for each other. Maybe I’m just getting in the way, ya know?”

“Aaron…no. It’s not that way and you know it.”

“All I know is what I see.”

“Is that what you see?”

“Yes.”

She hung up on me.

The dockmaster called me at six the next morning. Jenn had found some razor blades.

+++++

I was up there by late morning, and her psychiatrists at the hospital were convinced this attempt had been a classic ‘cry for help,’ that her cuts hadn’t been deep enough to damage the tendons. But there was another complicating factor.

Yup. Pregnant. Timing worked out about right, too. Our sunbaked idyll had been more than productive musically. And now she wanted to abort the fetus. There was no point, she’d told her docs. She’d destroyed all her chances for happiness, just like she always did, so why bring a kid into that world? Why not just kill everything about us? Take care of business once and for all time.

Maybe I was beyond caring that day, but it was beginning to feel like she was using suicide as a weapon to hurt everyone around her. Me, certainly, but her mother and father, too, and now she was going to carry to the next logical step, in her world, anyway. Kill the truly blameless, and I was stunned. Too stunned for words.

When I went in to see her I told her as much, too. Kill that kid and she’d never see me again. Simple as that. I left the hospital and went down to the marina, listed the sailboat with a broker and flew back to LA that evening.

Yup. Cold. Heartless. And tired of going round and round on her psychotic merry-go-round.

Her docs called me two days later and said she’d opted to have the abortion. It was done.

And so was I.

With her, anyway.

Not with sailing, as it turned out. Not by a long shot.

There were a couple of guys down in Costa Mesa working on a new 38 footer, and I drove down to see them, and the boat they were working on. They called it the Alajuela, named after a city in Costa Rica, and work was well underway on their second hull when I showed up on their doorstep. By the time I left later that afternoon I’d bought the next available boat, and would have her in a little less than a year, so I went home and retreated to the studio.

Jenn, of course, started calling as soon as she got back to Newport.

I, of course, changed my number.

She started coming up to the house.

I asked her to leave, and never return. After the third return I called a lawyer, had him serve her with a restraining order – and out came the razor blades. I heard that anecdotally, of course. Her father didn’t call me. He called my lawyer, who told me. Another near miss, of course, but this time they put her away for a couple of years and in the end I didn’t see her for almost ten years.

She made her way into my music, however. The love I felt that day for her was as real as it ever was, and that was hard to reconcile. As hard as it was to reconcile the kid she so carelessly killed.

+++++

I wrapped up the album about a month before Troubadour launched, and the studio had released Idyll as a single a few months before. Well received, too, but not like Electric Karma’s albums, so when the new album shot up the charts two weeks after release I was as surprised as I was happy.

But I wasn’t into it anymore. I had moved on, was already planning for a life with Troubadour. Everything about her was planned for one thing, and one thing only. I was going to take her around the world, and I’d probably be going solo, too.

Refrigeration was built in, roller furling headsails too. A more robust self-steering vane was a must, and light air sails a must. I wanted teak decks again, and they relented, laid them for me, and by the time Troubadour hit Newport harbor she was mine, purpose built and ready to roll. I moved her to a friend’s slip at the Balboa Bay Club and fitted her out, packed her to the gills – in less than a week, then I went home for a few days – to say goodbye.

I decided to rent Pop’s house to a friend of mine, a musician, and in the end left the house in the care of my lawyer. I drove down to Newport, handed my car over to the guys at the boatyard and in the middle a foggy March night I cast off her lines and slipped out the jetty, pointed her bow to the southwest – bound for the Marquesas.

This fragment © 2017 | adrian leverkühn | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | hope you enjoyed…

I’m glad I checked before shutting down for the night. Found The Nice at YouTube, read Outbound with Emerson playing in the background. Nothing quite like the transitions from jazz to classical to 60 rock as the music drifts seamlessly and without boundaries. Made me think of being at sea with the currents going one direction, the surface wind another, while clouds above shifted independently of it all.

ah well

LikeLike

Kind of like life?

LikeLike

Fantastic. Couldn’t put it down.

Best wishes for a speedy recovery and a swift escape from the little room!

>

LikeLike

Thanks, J. Seems I can’t let go of 1968…

LikeLike

A sexier nurse might be nice but a caring one could be truely helpful. Nevertheless have a good recovery.

Christian

LikeLike

Thanks! I was hoping for caring and sexy…

LikeLike

Yeah.

Greatest part of my life happening in hospitals, sometimes on the receiving end, the most caring nurse I can remember was a nun(!) helping me through some difficult time long ago. Besides prohibited by situation, projections, her stature and attire I could imagine getting lost in her arms.

But to recover as fast as possible nurses have to be like the models in those TV-series.

Good luck

Christian

LikeLike

I think the longer one’s in hospital the more enraged the fantasy becomes.

LikeLike

Being bed-ridden after some major surgery it had been kind of comforting.

Specializing in Anesthesiology and Intensive care med. later I had to acknowledge there’s more to it than being just professional, for example the dependance on people knowing and caring about what they’re doing. The hardest part however had been to get a view of the emotional needs of patients and their relatives entrusted to my/our care and to handle that appropriately.

Caring matters and yes, having a sexy nurse would be the perfect icing on the cake. At least you’ve got WiFi and a trusty MacBook Pro.

LikeLike

Of course my brother in law is an anesthesiologist. Everyone calls him a gas-passer, too. I’ve always wondered why 🙂

I assume hospitals over there care for patients. They don’t here, or at least it feels that way. They only seem to care about your insurance while you check in, and that there are no plans to sue them after you check out. In between, they just don’t seem to give a hoot. I wish I was the only one who felt that way, too.

LikeLike

I can’t imagine where that nickname may have come from.

On the caring of our hospitals for patients I wouldn’t bet. Struggling to survive the consequences of a DRG-based financing system which assumes hospitals as sort of industrial factories leads to strange developments almost everywhere combined with lots of pressure on the staff. I appreciate having gone into retirement several years ago.

Hope you’re getting that caring and sexy nurse.

LikeLike

I couldn’t sleep last night, had a long talk with one of the girls while I was writing. A good vibe after…or maybe that was from whatever she shot in my line.

Trust is the thing. Trusting other people to take your life in their hands. Big stuff.

LikeLike

How could/would we live without?

LikeLike

Alone. Maybe on a sailboat, when trust died.

LikeLike