My, what interesting times we live in. Studies concerning the nature of time and consciousness reveal surprising new concepts almost every week, and our understanding of humanity’s place in the cosmos continues to evolve. As Mr. Spock would say…fascinating! Interesting times, indeed.

Music, of course, continues to evolve – year after year, style after style. One of the best ways to teach (or to learn, for that matter) is to build upon solid foundations of understanding of what “came before.” You learn to play chopsticks before you compose your first symphony, I guess. Or…you can’t understand the present without also understanding the past, and that applies to music as much as it does anything else.

Gordon Sumner, the poet from Newcastle, is an interesting case in point. His is a life full of surprises, yet also a life that has come full circle. His latest release, The Last Ship, is a sprawling two disc set of rearranged material previously seen, and though most are predominantly acoustic in nature, with a good measure of bawdy thrown in for good measure, the music is vintage Sting. There are Newcastle laments and sea shanties and so much more, so maybe a few will like strike a chord or two with you. While not exactly Holiday music, you might start with August Winds and see where his words carry you. Island of Souls is a deep look into what was, a little moody but a perfect lament. Practical Arrangement is a mature arrangement, yet classic Sting. Have fun.

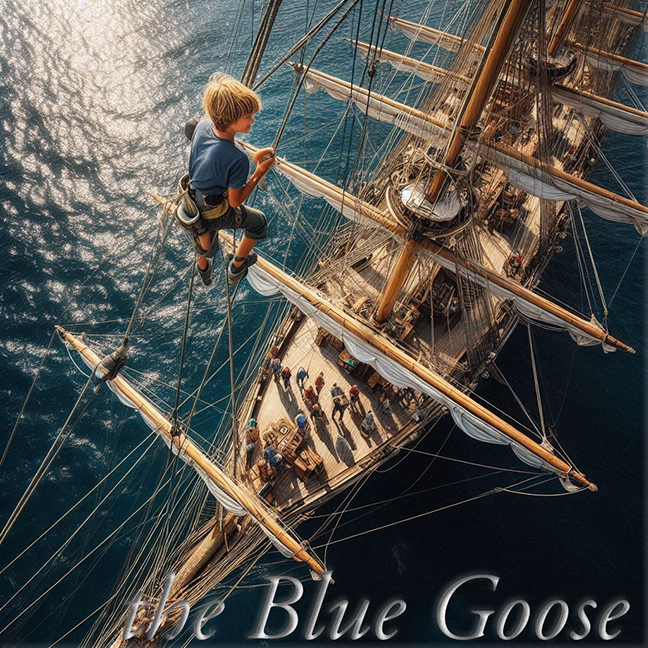

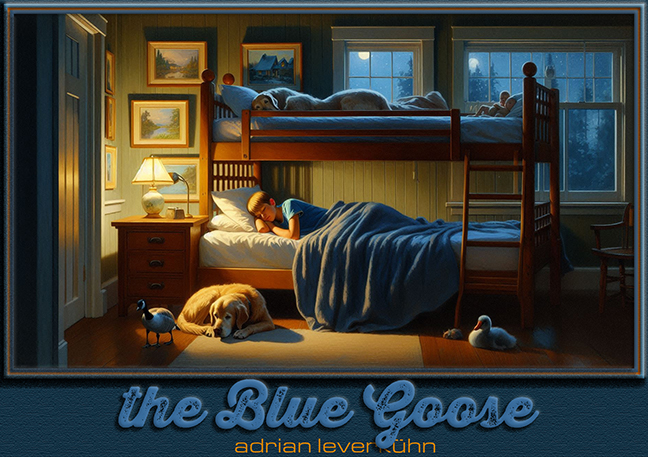

The Blue Goose continues here right where it left off, and I’m seeing a four part story taking shape (I thought three would do, but…alas…). It is cold and gray up here in the northlands, and an afternoon on a sailboat somewhere warm would sure feel good right about now. Anyway, enjoy, so put on some tea and cue up some Sting, then sit back and have a read.

The Blue Goose

Part Two

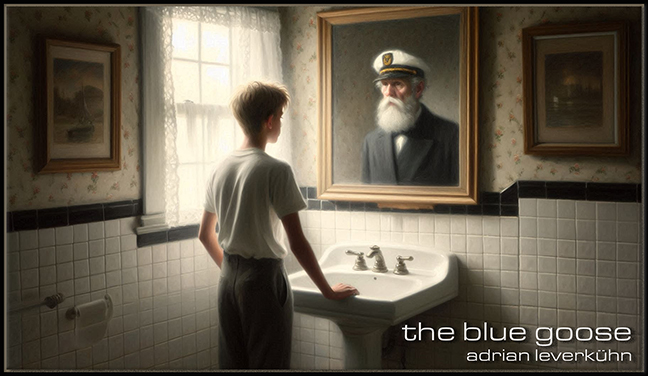

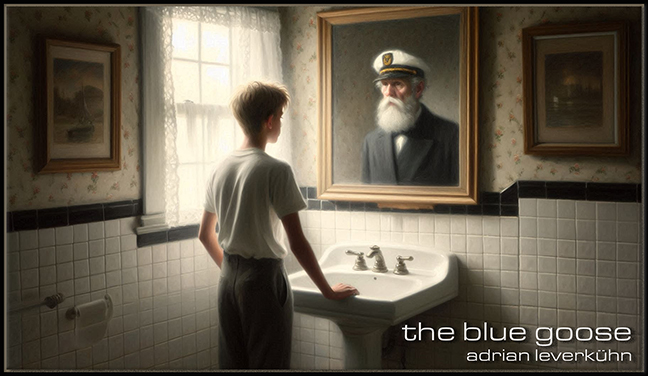

Hank looked at the face in the mirror, at first unsure of what its was exactly he was looking at. Not his reflection, certainly, but when the visage began speaking his hands began to tremble, his knees to knock. Daisy saw the man in the mirror and the hair on the back of her neck stood on end – before she turned and scampered under the bed, farting twice before she disappeared.

But then Gertrude came over to him and she pecked gently along his lower thigh, at least until he looked down at her. She was looking up at him, and she kind of honked once, something she hadn’t done before. Then he looked at the man in the mirror again.

“Is that Gertrude?” the man in the mirror said. “Might I see her?”

Hank’s eyes were fluttering now, as he hovered along the edges of consciousness, but he bent over and picked up Gertrude and brought her up to the sink. And once there she looked up at Hank before she turned and looked at the sea captain on the far side of the glass.

“Ah, hello – my old friend,” the reflection said, and Hank was now pretty sure he was dreaming. In fact, he was certain, and said just that.

“I’ve never had a dream like this before,” he began, “but anyway…who are you?”

“Me? Well, I’m Eldritch Henry Langston, Jr., and I suppose that makes me your great-great grandfather.”

“Do you know Gertrude from somewhere?”

“Indeed I do, but now is not the time to speak of such things.”

“Are you on Pegasus?”

“I am.”

“Tarawa? Are you in the lagoon at Tarawa?”

The man nodded. “Yes, right where you left off, in my log entry.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because I saw you, boy. Hank, think of what you’re experiencing as being like echoes, or ripples spreading across a pond. Sooner of later those ripples gain the far shore and bounce back, and Hank, you must begin to see that your thoughts are like that, too. And for some reason, it seems that a few of us in the Langston clan are able to hear one another’s thoughts and experiences, even across vast gulfs of time.”

Hank nodded. “I was reading something about that at school a few weeks ago. Some researchers say they have proof that some feelings, bad feelings like dread or even like when you feel you’ve been someplace before, those are actually thoughts traveling backwards through time. So, do you still go by the name Henry?”

“I do indeed.”

“Can I come where you are?”

Henry shook his head. “Are you sure you want to? Your grandfather tried once, too, when he was your age.”

“What happened?”

“He ran into the mirror and smacked his forehead, that’s what happened. He was not at all happy about it, I seem to recall.”

“So Grandpa Bud has done this?”

Henry nodded. “There is one thing you must remember, Hank. It helps if you’ve just been reading an entry in the logs, from something one of us has written.”

“So…that’s why I can see you at Tarawa?”

“That’s correct.”

“And it’s 1861, right?”

“Indeed.”

“I wonder if the Civil War has started yet?”

“The what?”

“The Civil War. The War Between the States, between the North and South.”

“I have no knowledge of such a thing. Tell me what you know.”

So Hank told him what he’d been learning in class the past few weeks, about slavery and abolitionists and the agrarian south versus the industrialized north.

“What about the Navy? What is the Navy doing?”

“I think they were trying to blockade the south, to keep Britain and France from trading with the confederacy.”

Henry nodded. “Do we get in a war with the British again?”

“I don’t think so. Why?”

“Because presently there’s a large British ship entering the lagoon. When did this war start, Hank?”

“In April, I think. April of 1861. Is it March where you are? That’s the date of the last entry I read…”

“Yes, it is indeed. So even if this new war has begun, there’s no way this other ship could know. How long does the war last, Hank?”

“Until 1865. The month of May, I think. Are you still going to Japan?”

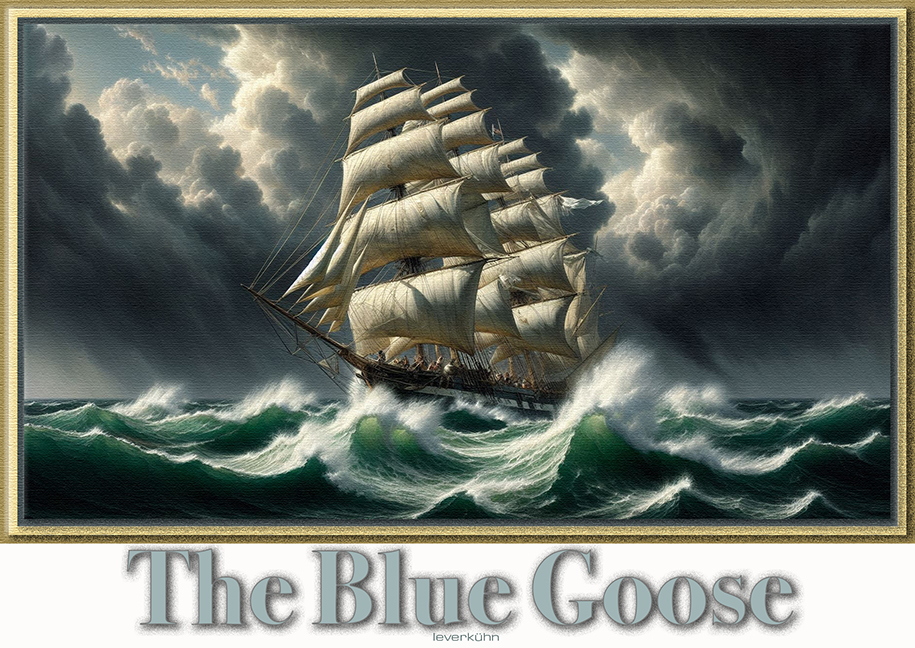

“Yes, indeed we are. With the successful return of Commodore Perry, the Congress has asked that we merchants send representatives to Japan with all due haste, yet I fear that’s why there’s a British frigate entering the lagoon at this very moment. I fear we may have trouble today.”

There was a commotion outside the captain’s cabin followed by the sounds of distant cannon firing, then explosions in waters near Pegasus.

Henry nodded and frowned. “I will see you soon, young Hank, but now I must take your leave…”

Swirling drizzles of condensation reappeared on the mirror and Gertrude turned to him from her perch along the edge of the pedestal sink, and again her eyes were enigmatically black and penetrating, focused on his own. Her head was barely moving; it was more swaying a motion than anything else, but as Hank stared into her eyes he felt something stirring inside, something less than a memory. Like a memory that wouldn’t take shape and form into words. A feeling like deja-vu, perhaps.

“Have we been here before?” he asked.

The goose raised it’s head until it was almost even with his, then she lowered her bill – in effect presenting her forehead – and Hank lowered his head to hers…until their foreheads were touching. Hank felt a wave of dizzying speed, a rush of kaleidoscopic light and he reached out with his hands to steady himself on the edge of the porcelain sink…

…yet then he felt his hands resting on warm wood…

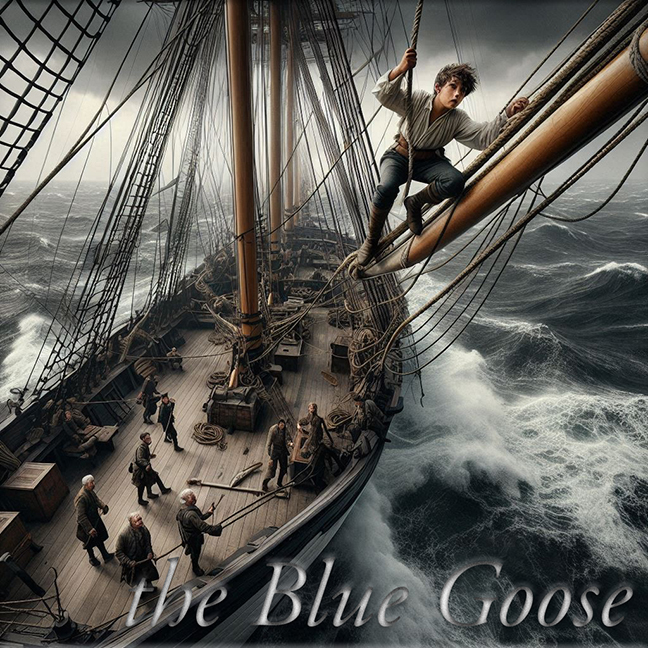

He shook his head, tried to push the swirling light from his mind’s eye but it was as if he was staring through the wrong end of a telescope. As if he was looking at a distant world through a distorted fisheye lens. Everything was far away and black mists swarmed, but he saw Henry running from his cabin and up into the light, up into the fight, and he could just hear Henry telling his men to prepare to make sail, then Hank heard running on the foredeck, Henry getting other men to weigh anchor. Across the lagoon the other American ship, the Bunker Hill, returned fire with the small battery on her foredeck, and Hank could just see that she too was preparing to get underway.

The black mist retreated and he smelled gunpowder in the air, heard seamen shouting, trying to make their voices heard over the sound of the almost continuous cannon-fire. He looked around, was suddenly aware that he was now in the captain’s cabin and that there was barely enough headroom for him to stand upright. He took a few steps and his forehead slammed into a deck beam and he grumbled, then stooped low and ran towards the stairs he had seen his great-grandfather running towards. He reached the stairway and grabbed hold of a bronze rail and took the stairs two at a time and in an instant he was on deck, standing beside Henry and one of Pegasus’s helmsman.

“Why are you here?” Henry shouted when he realized Hank was now by his side.

“I don’t know! What’s happening?”

“That British Man-o-war is firing at us…that’s what’s happening!”

“But you weren’t at war with Britain, were you?”

“No…we aren’t…” Henry sighed.

“So…what if they aren’t British? What if they’re pirates?”

Henry grabbed his “Dutch Telescope” and brought it to his eye; not one of the officers he could see on the British-flagged warship was wearing the correct uniform, but they were indeed wearing a uniform. A Spaniard’s uniform.

“Spaniards!” he shouted. “I will be poxed! Mr. Gilbert, get that anchor stowed. Mr. Talbot, get those foresails up, and prepare to tack to port as soon as we have some way on! We need sea room!”

“Aye, sir,” someone shouted.

Henry picked up a bullhorn that appeared to have been fashioned from brass or bronze, and he began shouting to Captain Anders on the Bunker Hill. “Anders! You there, Anders! Spaniards aft on the warship! Repeat, Spanish officers in command!”

Signal flags soon rose off Bunker Hill’s stern, first acknowledging the information, then more flags appeared, these stating Anders’ intentions to maneuver for a broadside, to engage the warship port side to port side.

“He doesn’t have room for that,” Henry sighed. “He’ll run aground before he makes sail!” He looked at the man-o-war, then at the water, and in an instant gauging both windspeed and direction as he ran through his options. “Mr. Gilbert, man the forward batteries and as soon as we tack prepare to fire, on my command! Mr. Cummings, you will go below and prepare the guns for a starboard engagement, and get the men to hop-to or they’ll be eating mud for their supper!”

Henry then handed the telescope to Hank. “Keep an eye on her officers,” he said, his voice steady. “Tell me when they react to our movements.”

Three large foresails dropped above Pegasus’s bowsprit almost simultaneously and began pulling. The ship began slipping through the water…

“You there, Anderson, go get the mizzen staysail organized. Mr. Lightfoot, get that mizzen up now, and keep her backed until we’re over.”

“Aye, Captain.”

“Hank, take the helm, would you?”

“Sir?” Hank replied, too stunned to think straight.

Henry’s eyes were majestic, like a falcon’s in a dive, yet his voice was still eerily calm. “Take the helm. Now, if you please.”

“Yessir.”

“And ready about, Mr. Talbot!” Henry shouted as another broadside, once again aimed at the Bunker Hill, fell short.

“Aye-aye, Captain!”

“Alright, Hank, make your helm left, about sixty degrees.”

“Left sixty,” Hank repeated. He looked at the compass card, saw their current heading was 340 degrees, so left sixty meant come to 280 degrees and so not quite due west, then he noted the four cardinal points on the compass and easily worked his new heading out. But the wheel was heavy! It took almost all his strength the turn it, and while Pegasus responded slowly his grandfather didn’t seem to think anything was amiss.

“Mr. Gilbert, ready your mounts to fire!” Henry paused, gauging the wind. “Right! Fire!”

Two cannons on Pegasus’s bow fired and while one round fell short one did not. This shot ripped through the mid-deck near the man-o-war’s main spar and a vast cloud of rigging fell away. A moment later her main mast slowly tilted and some crewmen could be seen falling into the water.

As the man-o-war began falling off the wind, Bunker Hill was unexpectedly going to be able to get off a full broadside with her port batteries, just as Pegasus started to come into range for a starboard broadside. Hank was trying to see the geometry of the engagement in his mind as he kept his eye on the compass card, and if he had it right it looked like an equilateral triangle was forming, with the man-o-war at the apex of the pyramid and the two American ships anchoring the base of the triangle – but with both their broadsides simultaneously coming to bear on the target.

“Mr. Cummings!” Henry shouted. “Prepare to fire – on my command!”

“Aye, sir!”

“Hank, another ten left please.”

“Ten left!” He kept the wheel over and he was sure he felt water moving over the rudder somewhere down there beneath the ship.

“Mr. Cummings, fire the starboard batteries!”

Pegasus seemed to lurch sideways under the force of the cannonade, and his view off to the right disappeared in clouds of blueish-white smoke – then Bunker Hill’s broadside cut loose. She had two gun decks and even from this distance the shockwave from twenty-four cannons firing at once was staggering. Smoke cleared and the man-o-war was ablaze, bright orange flames coming pouring out of the gun-ports on her starboard side. Men were diving overboard as the fire spread, and when Henry looked through his telescope he nodded, satisfied with the results of their combined attack. “There’s no one on her helm now,” he said, his voice almost a whisper.

“Mr. Cummings? Are we ready to come alongside and board her?”

“Almost, Captain! Ready to fire again, Captain!”

“Fire then, now!”

“Aye, sir!”

Maybe five seconds passed before Pegasus let loose her second broadside and that was the end of the man-o-war; a white flag was hoisted off the man-o-war’s stern just after Bunker Hill’s second broadside hit her bows. The ship’s once proud bow-sprit fell away, blown in half by Bunker Hill cannonade, this loss taking the foremast down in a loud series snapping stays and splashing timbers. With no one on the helm and no one sounding as the ship entered the shallow lagoon, the man-o-war slammed into a reef and shuddered to a stop – just as fire was engulfing her lower decks.

“She’s dead,” Henry sighed, “and ’tis a pity,” he sighed as he watched the enveloping chaos through his ‘scope. “Well, perhaps there will be something to be salvaged.”

Her powder ignited and the man-o-war’s main deck heaved upward and hovered there indecisively, then the ship fell in on itself, her back broken and fires beyond control. Within seconds she began to settle by the stern, yet only partially sinking down in the shallow lagoon, her spreading fires soon engulfing the remains of the ship. Hank could see a few dozen men swimming away from her, but Henry saw something more troubling still.

“Sharks,” he muttered quietly. “Mr Gilbert! Prepare to lower away the longboat! Sharks in the water! There!” he commanded – as he pointed just aft of the smoking wreck.

And Hank smelled carnage everywhere. Black smoke hung over the water near the man-o-war, white smoke from cannons clung to Pegasus and Bunker Hill, and soon enough the screams of men fighting off sharks filled the air too, joining into a surreal, macabre cacophony of death.

But just then several people emerged from the passenger cabins just below, near Henry’s cabin in the aft section of the ship just below the deck he was standing on. Most were reasonably well dressed, indeed, one of the men looked rather prosperous. So did his wife.

And, Hank soon realized, so did the man’s daughter.

She was impossibly cute too, and though she probably was no older than he, she was so pretty it seemed as if the mere presence of the girl took his breath away. Her mother was dressed quite well in the fashion of the day, a long dress with ruffles and frills adorning her sleeves and neck, but her daughter seemed not to care for such things. She was dressed in simpler attire, a blue and white gingham skirt and a very plain white blouse…and no shoes! Indeed, her checked skirt looked recently made…

She had to be one of the survivors from the whalers lost off the Cape. As he watched her she indeed seemed a little too unsure of her surroundings.

“Mr. Gilbert,” Henry shouted, “will you get that boat underway, while there are yet men to be saved!”

Hank reluctantly turned away from the girl and walked to the starboard rail and he looked down at a well-kept skiff, perhaps twenty five or so feet long, as it pushed away from Pegasus. Four seamen started rowing and Mr. Gilbert stood to the boat’s tiller, steering for the smoldering hulk of the still burning man-o-war. The water beneath Pegasus was shockingly clear, a clear light blue he had never seen before, and certainly not ever in the Connecticut River below the house in Norwich.

And he could see the sharks now, too. Missile shaped torpedoes, silver-gray and fast, homing in on the struggling survivors thrashing about in the water, and when their dorsal fins gained the surface Hank saw that they were black-tipped reef sharks, known man-eaters and frenzy feeders typically found in shallower lagoons throughout the South Pacific…

The passengers walked to the starboard rail and looked at the unfolding carnage, but the women quickly turned away when they realized exactly what was happening out there. But not the girl, Hank noticed. No, she held onto the heavy wooden rail and leaned out just a bit – and he thought it looked as if she was studying the scene, perhaps trying to memorize the sequence of events.

But just then the girl turned and stared right at Hank.

He was standing by the ship’s wheel and there wasn’t another soul nearby so he was certain she was looking right at him, and that time her gaze really did take his breath away.

Yet he held her eyes in his; he did not look away.

Nor did the girl, until she decided to walk up on the poop deck where he stood.

It wasn’t far. No more than twenty feet or so, but she had to climb the modest stairs first and he watched her movements as she made her way up the broad wooden steps, as she walked right up to him.

“I haven’t seen you before,” the girl said, and it was more a statement than a question.

“I’m just visiting,” Hank replied – and he knew his words were a little evasive.

“But where have you been?”

“He’s been locked away, hard at his studies, Miss Tomberlin,” Captain Langston said as he came to Hank’s aid. “This is Henry Langston, Ma’am, and he’s my grandson. He’s aboard as a provisional midshipman, learning the basics of seamanship and navigation on this voyage.”

“Oh, I see,” the girl said, and Hank could clearly see that she believed not one word Henry had just told her. “So tell me, Master Langston, what is our current latitude and longitude?”

Hank looked at the girl and grinned, all the while trying to remember the position he had seen entered in the logbook he’d been reading in the library. “Our current position is one degree twenty-seven north latitude by one hundred seventy two degrees fifty six east longitude,” he said easily, “if I’m not mistaken.”

“Very good, Henry,” the captain beamed, then turning to the girl. “He’s been helping with my log entries,” Henry said, grinning. “As a matter of fact, young Henry, I thought you were supposed to be in your cabin doing your words?”

“I was, sir, but thought it best I come topsides during the engagement.”

“Yes, your presence did indeed prove useful. Very well, Master Henry, you’re dismissed.”

“May I stay topsides, Captain. In case the the physician needs a hand while tending to the injured?”

“Oh, yes. Carry on, then. Report to Dr. Chamberlain on the foredeck. And now Miss Tomberlin, you shall retire to your cabin before the injured have boarded. Is that clear?”

The girl noted the stern tone in the captain’s voice and she seemed confused, almost angry by that sudden turn. “Why must I do so, Captain Langston. I surely won’t be in the way?”

Henry now turned the full force of his manifest authority on the girl, accompanied by a withering stare. “Miss Tomberlin, shall I have Midshipman Langston escort you to your cabin? You are too young to view such atrocities, and I will not have that on my conscience!”

“Then I think you should have this boy escort me to the brig, Captain!” the girl huffed sarcastically, though she was smiling inwardly. The old captain had been so easy to manipulate, because now she’d be able to talk to the boy without his interference, and far from all the other prying eyes onboard.

“Midshipman! See this lady to her cabin, if you please, then report to Dr. Chamberlain.”

Hank grinned. This outcome was far better than he’d expected. “Aye, Captain!” he said, really getting into the act. “Miss Tomberlin, lead the way, if you please,” he added.

Nothing was far away on this ship, of course. Nothing was on a 170 foot schooner. Her cabin turned out to be fairly close to Henry’s, and was not much larger than the closet he and Ben shared back at the house in Vermont. And as she was indeed a shipwreck survivor, she now had few possessions with her. Indeed, what little she now possessed had been purchased for her in Valparaiso by Henry and the ship’s surgeon, Dr. Chamberlain.

“So tell me, Midshipman Langston, just what is a New England Patriot?”

“What?” he moaned, suddenly realizing he was still wearing his clothing from home…

“And what is that on your wrist?”

He reflexively moved one hand to cover the other, trying to hide the Apple Watch on his left wrist. “I’m sorry…what?”

“The device on your wrist. Show it to me,” she demanded – as she reached out and grasped his hand. Of course, as soon as she lifted it the watch activated and the display came on, and when she saw that she literally dropped his wrist and stepped away from Hank. “What manner of thing is this?” she whispered.

“It’s a device for telling time.”

Her eyes went wide and round. “You jest!”

“No, actually, it does. Here, look…” he said as he lifted his forearm up so she could see, but the time was still set to the New England time zone so the time shown was of course nonsensical, but the display was showing his heart rate and blood oxygen levels too, which were pulsing merrily away.

She looked at his wrist then at his eyes, and her gaze lingered there a while. “When did you come aboard, Midshipman?”

“Please, call me Hank, would you?”

“Hank? So, your name really is Henry Langston, like the captain’s? You are his relation?”

Hank nodded, but he wasn’t sure what he should or shouldn’t say to her, so he remained silent.

“And this shirt? Who are these Patriots?”

“A sports team in Boston, and now, if I may, I need to report to the surgeon.”

But as he began to step away the girl reached out and grabbed his hands in hers, then she leaned forward and whispered in his ear. “You can trust me,” she said to him with a gentle squeeze of the hand. “Whatever it is, you can tell me. I will never betray your secret, or your trust.”

And with that she let go of his hands. He looked at her again, then nodded.

“There’s something about you,” he said. “Something about your eyes. When I first saw you, well, I started to feel strange inside, almost like I was getting dizzy. Not like I’ve ever felt before, I guess.”

“I know. I felt that strangeness, as well.”

He nodded once, now feeling disoriented much more than before, so he then turned and left her alone in the tiny cabin, his mind a torrent of strange, inrushing emotions. He turned towards the only daylight within his grasp and made his way up on deck, now almost reeling. The next thing he felt was Henry grabbing him by the arms and carrying him into his sea-cabin, then the old captain placed him face to face with the mirror.

And it was the strangest thing, all these unfamiliar sensations.

At first he saw himself in the mirror, but then he saw his reaction from the far side, and a moment later he was standing at the sink in the bathroom of his grandfather’s house in Rhode Island.

“Hank?” he heard his grandmother asking. “Are you up yet?”

It was all he could do to hang onto the pedestal sink as he fought off wave after wave of vertiginous convulsions, and he could feel his thighs and shoulders twitching. Not gentle little twitches, but deep, jerky movements, and at one point he felt he was about to collapse right there beside the sink.

Then Bud was there, by his side.

“Looks like you picked up a bit of sun last night?” he asked – a little sarcastically.

“What?” Hank moaned.

“Don’t worry, boy, these feelings will pass soon enough, but the first time is hardest. Next time you go, you’ll be better prepared.”

“What?”

“Hank, you’re not the first of us to do this sort of thing. Even your father has been.”

“No…”

“Now hop in the shower. Your brother is loading the car right now, as we speak.”

Hank remembered now. Ben got new skis for Christmas, and he was going to get new ski boots before heading up to the Skiway tomorrow.

But he wanted to see his mother most of all, yet he wanted to get back to Pegasus, too. Ben could ski all he wanted, but his mother had to be in bad shape to still be in the hospital after almost a month. Yet Hannah and Jennifer really didn’t seem to care at all. And Hank understood that, to a degree. His mother wasn’t their mother, and maybe it was as simple as that – but that felt wrong, too. Elizabeth had been taking care of Hannah and Jennifer like they were her own children, and their reaction to her collapse seemed to lack not just empathy, but common courtesy. So many thoughts. He felt so confused. Lost in a forest of disjointed dreams, framed by entries in a logbook. What was real, and what was a dream…?

And what was her name?

The girl on Pegasus? Tomberlin, wasn’t it? But what was her first name? And why had he felt so disoriented by her? She was the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen, but did beauty make people feel like that? It was like he couldn’t think…at all…when he looked into her eyes. Had he grown as insipid as all that?!

But Hank – had – forgotten about his mom and dad the entire time he was on Pegasus, and he might’ve wondered why but for the lingering vision that girl’s mesmerizing eyes.

+++++

The psych ward at DHMC was located in a quiet wing on the third floor, not far from Judy Stone’s office, but even as he walked to his mother’s room Hank could tell there was something peculiar about this part of the hospital. There was something unfamiliar about mental illness in general, but now that the reality of suicide had come into their lives the dynamics of all their lives had changed. And Dr Stone was not at all sure she wanted someone as young as Hank on the ward, even if the boy was visiting his mother.

The sight of someone restrained in a bed is not a pleasant one. The sight of someone who has been refusing food for days is dramatically more unpleasant, and it is the sort of experience that gets seared into memory, especially to one so young. It is a sight that one simply cannot erase.

And try as she might, Dr Stone simply could not convince Hank that now was not the time to visit his mother. And Stone could not do so because Elizabeth Langston was getting close to death; indeed, she had been placed on a gastric feeding tube two nights before, yet somehow she continued to yank the tubes out. The night before this had very nearly caused a pulmonary emergency, when the yanking tube leaked the feeding solution into her trachea. Restraints were ordered, and Elizabeth had grown combative after her wrists and ankles were secured to the bed frame.

But the woman was adamant. She wanted to die.

And she was willing to starve herself to death in order to do just that.

Like many teaching hospitals, Dartmouth Hitchcock had an Ethics Committee. Unlike most hospitals, this committee was made up of philosophy professors and graduate students working in the Philosophy Department of a highly regarded Ivy League school, and, as such, this committee took its work more than seriously. They had been called in to assist the treatment team trying to take care of Elizabeth Langston, and members of the committee had been observing her care for days. Yesterday, members of the committee had interviewed her, trying to determine the validity of her claim, that she wanted to die because her life had been so corrupt. Was this wish grounded in reality? What was the totality of her life circumstance? Had she been suffering chronic emotional distress for years, or was this the emotional acting out of someone who, perhaps, really had no idea what they were asking for? Did she, in the end, fully comprehend the consequences of her request? This case, the the head of the committee knew, would more than likely become a published case study, so their actions would be studied, and scrutinized – for years to come.

The patient was a librarian at the college and had long been regarded as a model of her profession – right up until the moment of her break. Her husband was a physicist at the college, her children were all regarded as well adjusted and three of them were academically gifted. On the surface, everything about her life was as unremarkable as could be. Nothing they knew explained all this…

Yet under the surface trouble had been percolating for years.

One of the first things Judy Stone learned concerned Elizabeth’s relationship with her parents, and to her father specifically. Stone was fairly certain, given her profile, that the woman had been sexually abused, and that this one feature of her upbringing had grown into the one causal item that had corrupted her ability to form close intimate relationships with others. Just a few interviews revealed that the woman’s pattern of abuse as a child had produced a uniquely crippled psyche.

Elizabeth Langston had grown up consumed by the need to conceal her deepest wishes and fears, and so consumed was she by the need to conceal these things that she never revealed any of these things to anyone in her life. Classic repression. Easy to uncover, difficult to understand. And painful for all involved in her deceptions.

And it at first appeared that her children knew nothing about any of this, because – so far, anyway – Elizabeth had been unwilling to involve her children in her predations. Yet after a week in her care, Dr Stone was not so sure this was true anymore.

Ben was, by almost any measure, a gregarious, outgoing kid, and he had the potential to be a gifted athlete. Yet, and again by any measure, his academic performance had presented one red flag after another – and despite this his teachers had ignored each and every one of them. He was presenting with all the academic warning signs of someone being abused, from daydreaming to becoming moody when confronted, and already she’d learned enough to want to interview the boy. Yet even so, doing something so invasive over Christmas was hardly the best time to do something so unsettling, as who knew what might be uncovered…?

+++++

Bud and Hank got the heat going as soon as they arrived at the house in Norwich, yet the next thing Hank saw was evidence that someone had been in the house. Nothing was wrong, specifically, just certain things seemed out of place. But one quick trip to the garage revealed that their father’s Volvo was missing, and Bud immediately called the police. Ellen took Ben to the ski shop in Hanover, which seemed to settle the boy down a little.

But no sooner had the police arrived at their house than the Volvo turned up, and it was being driven by none other than Henry Langston. The police soon left and Henry enlisted his children to unload groceries from the back of his Volvo, and all the while Bud filled in his son on what had been going on over the past month, and Christmas, while he had been away.

“Has anyone been to see Elizabeth?” Henry asked.

“We were advised not to come until after Christmas. Ellen has talked to Elizabeth’s psychiatrist almost daily, but no one has talked to the children about any of this – yet.”

Henry nodded. “Well, I’m sorry you two were pulled into this, but thanks for being there for them. I know they had a great Christmas.”

“Hank has become very special, Henry.”

Henry turned to his father, because he knew what that meant. “Already? Where did he go?”

“To Pegasus, when she was at Tarawa the first time, with Henry on his first Pacific crossing, the trip he made in 1861 as Master.”

Henry smiled. “So, he met Linton Tomberlin. I bet he’s in love.”

“You were too, I seem to recall.”

“I was. No doubt about it.”

“Where have you been, if you don’t mind my asking?”

Henry pointed at the sun with a nod of his head. “Things are getting busy up there.”

“Oh?”

“Come on, Dad. Let’s fire up the Egg and put on some steaks. I got stuff for salad, too.”

+++++

Daisy was walking beside Hank, Gertrude was perched on his shoulder, and the three of them were once again walking up the hillside behind the house. There was a solid foot of snow on the ground and Daisy loved the stuff; she plowed along, stopped to sniff for grouse under fallen trees and around fluffy old snow covered pines, and they walked along until they came to one of the old Quaker churches formed by planted pine trees. Planted more than a century before, these churches were now little more than wildlife sanctuaries, but few knew of their existence, let alone what they had originally been intended for.

Pines had been planted in a broad cruciform, but only in outline, so now this church had walls of towering pines swaying in the breeze, and roofs of sheltering boughs covering the grassy interior, yet anyone could see the beauty of the resulting structure. Perhaps fifty people could have been seated inside the space, if the structure had ever been used as such. But probably not, for time left the planted chapel to grow on its own. And now, this church was occupied only by deer seeking shelter from passing storms. The animals bedded down up under the transept on soft grasses, and as Daisy walked around the area she sniffed around the flattened area lost in the scent of sleeping deer, while Hank, as he always was, seemed entranced by the sense of desolate space. Deer had found shelter here, perhaps for decades, and it was obvious why. With a foot of snow cover out beyond these trees where the deer lived, their landscape was a bitter test of survival, yet inside this sanctuary there was still soft grass to be found, and shelter from the howling winds and driving snow. In a way, Hank mused, this little chapel was more attuned to God’s word than anything yet fashioned by the hands of man.

And there were dozens of these chapels scattered among the settlements that had sprung up along the Connecticut River. Had these early settlers visions of using these chapels as places of worship one day, or had they meant them for wildlife to use? No one seemed to know, as few historians even knew of these chapels, but what a nice thought it was. He sat and looked up at the sky, at white clouds scudding along up there beyond the breeze, then he looked around as Gertrude hopped down from his shoulder and walked around pecking at the grass. He could just make out the shape of the cross in the sentinel-like formation of trees, and whoever had planted them had done so following a rigid formula.

Hank had found another such chapel when he was on a Cub Scouts camping trip two years before, and this second chapel had been near Mount Ascutney. He had counted the pines as he noted their placement, the same shape of a crucifix. The ‘arms’ of the transept were each planted with seven pines, with seven paces between each pine. Seven pines above the transept, fourteen below, so each arm of the crucifix had been planted in multiples of seven – but why? And the head of each transept pointed east, due east. Why?

Daisy came over and flopped down beside him, her nose lingering over the flattened grass, her eyes searching hidden contours and fleeting shadows. Gertrude extended her wings and tested them with a few tentative flaps, but then she just flew away.

And Hank watched, helpless as his expectations gave way to her instincts. Daisy looked up at him, her eyes suddenly full of reflected sadness. Like ripples spreading across a pond…

“Well…holy crow…” he muttered. This was turning into one bad day. He couldn’t see his mother and his father seemed to be living in another world. Certainly not this one. But…now this?

‘Has the universe decided to take a crap on me today?’ he sighed.

He stood and looked around the little chapel again but now, suddenly, this forest enclave was nothing more than a curiosity, and a very lonely one at that.

“Come on, girl,” he said to Daisy as he patted his thigh, the sound mostly muffled by the thick mittens on his hands. He made his way out the hidden opening and stepped out on the game trail, then he looked down valley towards Norwich and White River Junction, watching the last of the day’s sun falling on the summit of Mount Ascutney on the southern horizon. It would be getting cold out soon, real cold, and he hoped Gertrude would find someplace warm and safe…

But he needn’t have.

He heard fluttering wings then felt her light on his shoulder and he turned his head just enough to meet her gaze. “I sure hope you don’t do that again,” the boy said, “at least not while I’m alive.” He took off a mitten and reached up, rubbed the top of Gertrude’s head, and she bobbed along on his shoulder as they made their way down through the crunchy snow back to the house.

His father and grandfather were out back on the flagstone patio standing beside his dad’s smoker, a huge green thing shaped like a dimpled egg, and smoke was curling out of the little cast iron chimney on top of the egg. He had smelled burning charcoal and searing steaks from a quarter mile away and it hit him then, that was the smell of home, at least his home on the occasional good days the family had usually enjoyed in spring and fall.

Other than Christmas, winters in the Upper Valley had been bleak and dreary, but his dad said that was because Hank had simply grown so comfortable while being down on the water – all summer long. That was true enough, but starting in November it seemed like everyone had the Upper Valley Crud, a combination of upper respiratory and sinus infections, that didn’t leave until April or May, and that just made the dreariness all that much worse. So far he’d only had a mild case this year – yet it had cleared up as soon as he got down to the sea air in Rhode Island. He felt sure he’d start feeling crummy again soon, because he felt the sea in his bones. It was where he felt he belonged…

Hank kicked the snow off his boots as he walked up onto the patio, and as usual Gertrude fled as soon as she took a direct hit of smoke from the grill; she glided over to the patio door and tucked her head under a wing, waiting for Hank to come to his senses and get out of that nasty purple haze and let them both go inside, where they belonged.

His grandfather looked up at the commotion and smiled at Gertrude. A very special smile.

And then Hannah walked into the kitchen with Jennifer and Ben, followed a moment later by Ellen. Ben had his new ski boots in hand, carrying them by a little plastic handle looped through the upper buckles. The were the newest Head competition boots, white and very slick looking. Hank thought they even looked fast, ‘and at that price they should,’ he muttered.

Ben took off upstairs like a rocket, lost in fevered dreams of racing down Swiss mountains.

Ellen and Hannah started pulling stuff from the fridge and tossing a salad, while his dad poked the steaks on the grill, and after adjudging the bounce he turned them one last time to finish them off with a baste of lime and butter. A minute later he pulled them off the fire and put them on a preheated platter, then everyone went inside. Hank finally slipped out of his snow boots and woolen mittens, stopping to warm his hands up by the wood stove before heading into the kitchen to help set the table.

Which fell to Jenn and Hank that night. Then again, it always seemed to fall to them, but isn’t that just the way it is sometime?

“How was your walk?” Jenn asked as she handed him the napkins, her manner as easy as it ever had been, almost as if she didn’t care about a thing in the world.

“Gertie flew off while we were out. First time, too, but she came back a few minutes later.”

“I bet that was scary. You think she’s ready to go live in the wild?”

“I’m not ready for her to.”

“Okay, but what if she is?”

“Then she is. I won’t stop her. I couldn’t…”

“She was born in the wild, you know, so maybe she would rather be free…?”

“So why did I run into her, Jenn? Why did she attach herself to me?”

“Because you saved her life.”

“Exactly.”

“Do you think that means she belongs to you now?”

He shrugged. “I guess not…but maybe I belong to her.”

“Oh, you do? Well, I guess I would feel like that, too, if I was in your place.”

He looked at her and nodded. “Thanks. She means a lot to Daisy and me.”

“Thanks for what?”

“For understanding.”

“Do you remember when Ben left the back door open and Daisy ran off?”

He nodded. “Yeah, sure?”

“Well, she came back on her own, didn’t she? And she’s never done it again. I think maybe she learned her lesson.”

“And that was?”

“That it’s dangerous out there, and that you take care of her. Maybe she just needed that one little taste of freedom, you know? To understand just how good she has it with you. And maybe Gertrude needed that too.”

He nodded. “I hope that’s it.”

Ellen and Hannah carried in platters loaded with steaks and a big spinach soufflé, then Bud came in carrying the salad bowl, and soon everyone was seated around the dining room table passing plates around and talking – just like families everywhere do over dinner. But then, after a few minutes of that normalcy it dawned on Hank – that this was the first time they’d had a family dinner without their mom around, and he realized he felt all hollow and empty inside because she wasn’t with them.

“Has anyone been to see Mom yet?” he asked…and the almost carefree atmosphere around the table shattered into a thousand pieces as everyone fell to the floor.

But seeing this, Ellen replied casually, and she casually saved the evening. “Oh, I did,” she said, smiling, “and Dr. Stone is going to come by later tonight to talk with all of us. I think she wants to talk to us as a family, instead of in her office. That was nice of her, I think. Don’t you, Henry?” she added, looking her son in the eye as the question lingered in the air – apparent.

Hank’s father nodded, but he didn’t look up from his steak.

Then Bud looked at his wife. “Do we need to call her first?”

“I have her number,” Ellen said, grinning, “ and I’ll give her a call when we’re finished here.”

Bud grimaced, hating to spring this on the kids so fast – but, he thought, maybe this was the best way…? He wasn’t so worried about Hank, but Ben was another matter.

Ben had barely mentioned their mother, not since that night right after Thanksgiving. He had retreated into his daydreams since then and, Bud thought, he had been acting almost like he felt guilty about something.

But then, just moments after that singular thought crossed his mind, the hair on the back of his neck stood on end. Something wasn’t adding up right now, was it?

He sat back, and having suddenly lost his appetite, he did his best not to look at Ben.

“So, Ben,” he finally said, trying to change the flow of his thoughts, “which boots did you settle on?”

“The Head Comps, which are supposed to the best for GS.”

“That’s Giant Slalom, right?”

Ben nodded. “Right. Faster than slalom, not as fast as Super-G, or Downhill.”

“I thought you did pretty good on the Slalom course at the Skiway last year,” Henry said. “Why the change?”

“Slalom is getting too technical,” Ben said, reciting something he’d read in a magazine somewhere. “Besides, I want to go faster but I can’t join the Downhill squad until middle school. If I do good at GS, I might have a shot at making the squad.”

“How many from the program made the U.S. Ski Team last year?” Ellen asked, now regarding her husband carefully.

“Four made the Alpine team, and I think three made the Jumping squad. I don’t know how many made the Nordic team, but it was a bunch.”

“And that’s what you aim to do?” she added.

Ben nodded. “Yup, sure is.”

Henry looked up at that and smiled. “Good to have a goal like that. You put in enough hard work and who knows how far you’ll go.”

Hannah and Jenn were starting to feel a little left out and Hannah definitely wanted to take some of the spotlight now, so she cleared her throat and… “So, Dad, I got my second SAT scores in the mail. I got a combined 1550!”

Henry looked up at her and beamed. “Damn! Now there’s something to be proud of, kiddo! You get any letters yet?”

“One from NYU, one from Columbia. Do you think we could go down soon and take the tour?”

Henry thought a moment – which for him was difficult, as taking a college pre-admissions tour had nothing at all to do with quantum mechanics – but then he remembered where he was and nodded. “The week after New Years. Think you could manage that?” he said.

Hannah squealed with delight. “You betcha!” she said, suddenly ecstatic with this sudden turn of events.

Henry looked at his father then. “Dad? Think you could come with us?”

“Of course.”

Henry turned his attention to Jenn, who hadn’t spoken at all during their dinner. “And Jenn, did you get your PSATs?”

She nodded. “I did, yes, but I took the regular SAT, remember?”

“Oh, right. I knew that…! And…?” her father asked.

She looked at Hannah then shrugged. “Could we talk about it later?”

“No need to be shy around this table, young lady,” Bud said, prodding her a little.

Jenn sighed. “Sixteen hundred,” she sighed, looking down.

“But that’s a perfect score, isn’t it?” Ellen asked.

Hannah visibly deflated and now their father understood Jenn’s reticence.

“Did you get any letters?” Henry asked.

“Three so far. Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.”

“Nothing from Dartmouth?” Henry asked.

“Yeah. Them too,” she added with a quiet scowl. “And a couple others, I guess.”

Ellen watched the old dynamic take shape, yet she also kept an eye on Ben – who seemed to get smaller and smaller as the girls’ scores took precedence over his ski racing. Only Hank seemed genuinely proud of Jenn and Hannah, even more so than the girls’ father, and that just piqued Ellen’s curiosity.

“Hank?” she asked. “Did you tell your father about your Christmas present yet?”

Bud cleared his throat and shook his head just a micron off center. His gift of The Blue Goose, the Langston 28 in the finishing shed, was still not open knowledge among the kids, at least not yet. Hank followed the exchange with his eyes and shrugged.

“I’m sending him to sailing camp down in Newport next summer, Henry,” Bud said…which was true, of course, but it also postponed the inevitable outbursts of sibling jealousy a little longer.

“Oh? Which one?”

“The racing camp at U.S. Sailing, in Newport.”

Henry nodded. “470s, right?”

Hank nodded. “Yessir. Same as you, when you went there.”

“Good. Fun little boats.”

‘Whew!’ Bud thought. ‘Crisis averted. For now, anyway.’

Jenn cleared her throat and looked first at Bud, then at Hank. “So, when are you going to tell us about The Blue Goose?”

Bud scowled and looked down at his hands. Ellen smiled triumphantly, because she detested secrets. Hank shook his head, then threw a couple of hate bombs in Jenn’s direction.

“What’s The Blue Goose?” Henry asked.

“A 28 we took on trade last summer. Ben Rhodes and some of the team cleaned her up a bit, and then your mother and I decided to give it to Hank for Christmas.”

“What?” Hannah cried. “A sailboat?”

“Dude! That’s awesome!” Ben said, smiling broadly while he fist-bumped his brother.

Jenn smiled. ‘Mission accomplished,’ she told herself, as always intent on upsetting the applecart.

But Jennifer’s grandfather studied her, too, and he wasn’t at all sure he liked what he saw in her eyes.

+++++

Dr. Judy Stone, Elizabeth’s psychiatrist, arrived after the kids had finished helping Ellen get the dishes cleared and into the dishwasher, and after greeting everyone the physician asked to talk to the adults for a moment. Ellen and Emily Stone, Daisy’s vet, took the kids upstairs and they all huddled together, all six of them, and as it was the largest, they did so in Hannah’s bedroom. Emily asked the boys how their Christmas went and so of course Jennifer had to go into one of her passive-aggressive fits of jealousy by blurting out the details surrounding Hank’s very own sailboat. Ben, of course, couldn’t talk about his new skis and boots enough, while the girls acted like spoiled brats, bemoaning the fact that all they got were new laptops.

Ellen, on hearing this, decided she’d had enough. “Hannah? You do recall you have a graduation coming up? What do you suppose your grandfather will get you for the occasion? But oh, wait, how do you suppose he’ll think about that if he hears you talking like you are right now?”

It was flipping off a light switch, Emily Stone thought. The girls were instantly back on their best behavior, smiling pleasantly as if nothing had happened, and in a way the veterinarian admired their resiliency. Yet, in another way, she now regarded them warily. Hannah’s plastic expression was bad enough, but Jennifer was showing the obvious signs of middle-child syndrome, acting out her petty jealousies while being remarkably clever about how she masked her inner feelings. Jennifer was, she thought, maybe the most toxic element in this family. Maybe – the – toxic element. Watching these kids, and listening to them, were of course why she had come this evening.

Judy had mentioned her misgivings about Ben to Emily – so she could watch for signs of trouble, but now she wasn’t so sure that he was a problem. She watched Ben carefully but he really seemed to be a perfect example of a happy-go-lucky misfit, always living in the moment and without a care in the world – beyond next seasons lineup of skis and ski boots. And, she knew, he probably wouldn’t change until he was seventy years old. If then.

Hannah seemed a simple narcissist, self-centered in the extreme but not particularly dangerous. Despite her tendencies to see the world as a series of Pavlovian responses to immediate wants, she didn’t appear to be as malignantly manipulative as Jennifer – but that was just a simple assessment after a half hour of watching the kids talking to one another. Jennifer, on the other hand, was studying what everyone said, always looking for an momentary advantage or a weakness to exploit, and the girl was smart. Possibly a sociopath, definitely way up there on the narcissistic personality disorder spectrum, Emily soon began to feel uncomfortable around Jennifer. Worse still, she was now sure the girl’s grandmother felt that way, too.

Which left her own personal favorite, Hank.

The boy seemed like a perfect son, and like anyone who had taken a bunch of psych classes as an undergraduate, when anyone appeared perfect it was time to raise the alarm.

Yet as they talked it was obvious his only concern was for his mother, but also, of course, his parent’s deteriorating relationship before her collapse. These feelings were natural enough and quite understandable, yet she could tell he was holding something back. Something big, something very important to him. Maybe even more important than his mother.

And she wondered what that could be…then it was time for all the family to talk to Judy.

+++++

One of the most troubling aspects of Elizabeth Langston’s family background became apparent as soon as she was committed for psychiatric observation. When contacted, Elizabeth’s mother expressed no interest in coming to visit her daughter, and it turned out that Elizabeth’s father was deceased. She had two sisters, yet her mother seemed reluctant to pass along any sort of contact information. After her first two attempts failed, she enlisted the support of the police department in Boston, who were able to uncover the necessary information through other means. Judy called both of them, and two days later they both made the trip to Hanover. Henry picked them up at the airport in Lebanon and took them to the Norwich Inn, because he wanted them close to the boys…just in case.

Because after his meeting with Judy Stone two nights ago, Henry was now all too aware that his wife was skating along the razor’s edge between life and death. More troubling still, Elizabeth had chosen death and it was only through the nonstop efforts of Stone and the Ethics Committee that his wife was still alive. The committee had come to the conclusion that it was simply too soon to discontinue life saving interventions, because Elizabeth’s case still fell into the “acute” phase. If Elizabeth could maintain that the pain of her existence was simply too great to bear, and do so over an extended period of observation, the Committee’s recommendation might change. But not now, not yet.

Oddly enough, it had come as a shock to Henry that his wife had family, and now he wanted to know more about his wife’s childhood almost as much as Judy Stone did. It had always been a ‘red flag’ that she didn’t have any family, and he had blithely accepted her explanation that they had been gone for years, so she had flat-out lied when she maintained she had no other family. Looking back on that now he could clearly see the error he’d made, if only because he was now learning that his second wife was a master of disguises. Henry could see deeper patterns emerging, too. Elizabeth had grown accustomed to doing whatever was necessary to keep people from uncovering her past, from lying about her family to refusing to talk about her childhood, and now that he could see the tumblers falling into place he was dismayed about his careless approach to dating her.

But now he needed to know: what was it about her past she wanted to conceal?

With that question now out in the open, both Judy Stone and Henry decided it was time to contact Carter Ash, to see if she had talked to him about any of these things. Still, it was decided that Judy would handle all these interviews, simply because Henry was in fact emotionally compromised where Ash was concerned. Yet it turned out that Ash was as much in the dark as Henry had been; Elizabeth had in fact told Carter that she was a widow, and when he found out at Thanksgiving that this was a lie, she had evaded his further enquiries by saying he had simply misunderstood her, that she was merely separated. Carter had begun to distance himself after that, yet when he learned what had happened to her, he was concerned for her well-being, and for that of her kids.

Hanover was a small town and Judy knew that soon enough word would spread that the children’s mother had tried to kill herself. Maybe news that Elizabeth was a suicidal in-patient wouldn’t spread as quickly, so that would need to be a consideration going forward, which was why she was beginning to think that the boys might do better at their grandparent’s place in Rhode Island, at least for the remainder of this academic year. Hannah and Jennifer, on the other hand, were both too close to graduation, and pulling them out of Hanover High would create more problems than it might solve. She spoke to Henry about these possibilities and he agreed with this thinking.

But Henry asked his dad what he thought.

Perhaps many grandparents would rebel at the merest mention of taking on such a burden, but not Bud, and certainly not Ellen. In some ways this was like a dream come true to Ellen, as she missed having children to take care of on most any morning. She had always loved getting up early and making breakfast for her children, then getting them ready for school. She needed something like that, and perhaps more than either was willing to admit, but Henry was nonetheless surprised by the faint little smile he thought he saw cross his father’s face when he brought it up.

“Why don’t we ask the boys first?” Bud said.

“Because,” Henry sighed, “Hank won’t have a problem staying down there with you, but Ben will. Ben won’t want to move away from the slopes, or the ski team.”

“Then he stays,” Bud said with a shrug. “And if he stays, we shouldn’t single out Hank. He might get the wrong idea…”

“Mom? Would you mind moving up here for the rest of the school year? At least until Hannah graduates?”

Ellen looked at Bud and he could see it in her eyes.

“Of course she can,” Bud sighed, even knowing how much she would be missed in the front office. “But maybe Hank could come down on weekends to help me get caught up…?”

Henry nodded. “I can handle that. Yeah, especially with that new boat. I like it, Dad. That’ll keep him focused.”

It never occurred to either that Hank was the real empath in the family, and that all the doubts and uncertainties surrounding his mother and her illness were beginning to crush the life out of him.

+++++

Carter Ash called one afternoon and asked Henry if he could come over to the house, and he only said it had something to do with his own son. Given the circumstances, Henry reluctantly agreed.

It was New Year’s Eve, of course, and Ben was just getting in from the Skiway when Carter and Huck arrived. Henry met them out front, mainly to ask what all the drama was about, so he was a little amused when he learned it had to do with Hank having mentioned that he would get Huck a brochure detailing the Langston 28, which seemed to possess the meaning of life to Huck…in the boy’s current state of mind, anyway.

‘Oh, my,’ Henry thought, ‘I can’t wait to see this…’

So Henry walked with them inside and asked Hank to come down, and as soon as Hank realized what this was all about he got into it, too.

“Well, my Grandfather is here this week. Would you like to meet him? And maybe he can bring one up for you one weekend, too…”

“What’s this?” Bud asked.

“Oh, Huck has a real thing for the 28,” Hank began. “I kinda promised I could get him a copy of the brochure, too.”

Bud had at first regarded this boy with cool detachment, but when he heard this news his smile said it all. “A brochure, eh? What about that 28 we have in the finishing shed? Maybe he’d like to come down and take a look at her one weekend…?”

Huck was beside himself now, for this was like a dream come true, and he wheeled around and turned to his father. “Dad? Could I?”

Carter looked at Hank, then at Henry. “Fine by me,” Carter said. “Are you sure you don’t mind?” he asked Bud.

“Love to have him. I’m going down tomorrow, so if you can get him over here by noon? We’ll bring him back in a couple of days, unless you want us to just keep him,” Bud said, adding that last bit with a ferocious grin, mainly for Huck’s benefit – but Carter grinned too.

“I think he’d love that. We’ll be here in the morning.”

“How much stuff should I bring?” Huck asked.

“Would two nights be okay?” Bud asked Carter.

So a few minutes later a very happy Carter Ash, Jr., departed, no doubt with visions of sailboats dancing in his mind, and Hank smiled as he watched them leave.

“That was merciless, Hank,” Bud said, smiling appreciatively. “You did well.”

“Think we should get him a brochure, too?”

Bud rolled his eyes as he went to help Ellen in the kitchen, repeating “Merciless,” one more time, just for good measure. “The kid has a decent sense of humor,” he told Ellen as he got to work.

“And I wonder where he picked that up?” Ellen muttered under her breath.

+++++

Henry was sitting in a conference room at the medical center, sitting with Rebecca Nichols and Mary Stuart, Elizabeth’s two sisters; they were waiting for Dr. Judy Stone to arrive, and both women were nervous. By tacit agreement, everyone had refrained from talking about Elizabeth until they were joined Elizabeth’s treatment team. Sitting there with the women, Henry was only getting more curious as the minutes passed.

And while Dr Stone appeared a few minutes early, the rest of the team dragged in more slowly. After introductions were finally made, Stone went in with guns blazing; she asked the girls point-blank what their childhoods had been like, especially regarding their father.

Rebecca looked away; Stone saw the woman was biting her lower lip and her left eyebrow was already twitching. Mary, the oldest of the three, nodded and sighed, taking the lead – as if this was the role she was used to taking when it came to these things.

“Did you ever see the movie ‘The Great Santini?’” Mary asked – to no one in particular.

“I read the book,” Stone replied.

“Well, that was our father. On a nice day. Except when he got drunk.”

“So, was your father a Marine?”

“No,” Rebecca sighed. “Our father was also The Great Pretender. I think the longest job he held was working at a Pontiac dealership in Worster, at there used car sales lot. He could schmooze your ears off, tell you anything about everything, and probably ninety percent of what he said was made up on the spot. He told all our neighbors The Great Santini was about him, that he had been some kind of hotshot pilot in the Marines.”

Judy Stone nodded, because it fit what she knew so far. Elizabeth was shaping up to be a pathological liar, so just like her father, and that meant anything she told anyone on the treatment team was suspect, and her statements would have to be verified – one miserable lie at a time – because sometimes a kernel of truth was hidden inside these lies, and that one truth often held the key to successful treatment.

Stone looked at the girls, and she hated to ask this next question but she had to – even though she was already sure she knew the answer. “Were any of you abused?”

“You mean sexually?” Mary asked, looking down at her hands.

“Sexually. Physically. Verbally. It really doesn’t matter which. I’m looking for patterns, and I need your help to see what I may have missed.”

“Does being pushed down and fucked in the ass count?” Mary asked, her voice a feral snarl.

Stone met the woman’s cold fury head-on. “Did he do this to you? Or to Elizabeth?”

“How ‘bout all three of us? Do we get extra points that way?” Mary snarled. So, she was using brutal sarcasm to mask the pain and embarrassment she’d been hiding all her life.

Stone held her gaze, nodding inwardly. But if Mary’s resistance was taking shape as angry sarcasm, helping her to keep distance from the pain she was re-experiencing under the watchful gaze of a half dozen shrinks was the least she could do. This wasn’t unexpected, yet she wasn’t fully prepared for what the women told her over the next hour and a half. Tales of being sodomized, forced into oral sex with her father and his friends, of being sexually brutalized with everything from broomsticks to beer bottles. When Mary was in her teens he’d tied her up in a box he’d built in their home’s basement, then he’d had even more friends from work come over and take turns sodomizing her. Mary found their mother down there one afternoon, bruised and bleeding after her father and his friends had done the same to her. And their father had gone on like that for years. Then there were years of silence, years spent learning how to deceive, how to cover up their feelings. Mary had somehow managed to get out of the trap after high school, and she’d fled to Northern California, ending up on a commune growing weed. She broke away from that group, which was little more than a pseudo-religious cult, and she made it to Seattle where she eventually finished college. She worked as a coder at a large software company there, and claimed she had a partner.

Rebecca experienced many of the same violations, but eventually their father began having his friends and their wives over for swinging parties in the basement, where she and Elizabeth were passed around like party favors. And it happened that their mother participated in those little get togethers, too.

Their father’s abuse took on many other forms, as well. Usually verbal abuse, but occasionally beatings when they didn’t do as he said or when they stayed out too late. Everything in their father’s house was a capital offense. Everything always felt like life or death, like there was no in-between, just his way…or else.

Stone soon regretted not interviewing the women separately, as now she was simply not sure how much of this was rehearsed and how much really happened. If Elizabeth was a pathological liar, the odds were pretty good that both of these women were too, assuming even half the things alleged were true. That, however, would be law enforcements job.

Henry had no way of knowing that the things he was hearing were actually fairly routine stuff for attending psychiatrists at any medical center in the country. These types of assaults were so common it almost felt mundane to the professionals in the room, but the more he heard the sicker Henry began to feel. His wife hadn’t been raised in a traditional, loving family; she had been kept as a pet by monsters, and it was a wonder she had been able to function at all. On any level.

And the more he thought about the things his wife had endured, the things she had compartmentalized and walled-off from him, the more he began to love her. She had pretended as long as she could, until the facade began to crumble under the weight of her dissatisfaction with life. In her world she must have felt unloveable, because no one treated anyone they loved with such careless disdain. Certainly not a parent.

“Henry?” Judy Stone asked, after she saw the expression on his face. “Are you feeling okay?”

He shook his head. “No, no I’m not. I’m sorry, but is there a restroom around here?”

One of the shrinks got up and both men left the room. Henry did not come back.

And Judy began what amounted to a painful cross-examination of the women’s stories, checking off questions and looking for inconsistencies in their retelling. But when nothing emerged after almost an hour she concluded that the women had been as truthful as possible, given the circumstances.

“Are either of you in treatment?” she asked as they wound up the session.

Both shook their head. ‘Survivors guilt,’ Stone knew was one more piece of this evolving puzzle. They blamed themselves as much as they blamed their parents, and without help they always would. She discussed treatment options, offered to help them get funding from foundations that assisted women in their position. Neither was interested. Judy gave them her card, told them to keep in touch if they remembered anything else of importance.

And that was it. Stone now knew what she needed to know.

Two members of the Ethics Committee had attended, and both were a little shell-shocked.

“They make a strong case for chronic dissociative disorder,” they said. “It will be harder to deny Elizabeth’s request to stop gastric feeding.”

Which meant after a childhood full of traumatic abuse, the system was now going to allow her father one last victory. There would be no accounting. No justice served. Just a woman alone in a hospice bed slowly starving herself to death as her demons fluttered overhead, waiting for their last moment of torment together.

But Judy Stone wasn’t prepared to stop trying. Not yet, anyway. And now she knew she had a strong ally.

+++++

Bud listened to Hank and Huck chattering away just like eleven year old boys – and from Hanover all the way to the coast; by then he was he was about to lose his mind. They were too young to talk about girls, too old to talk about playing with toy soldiers, and just about the perfect age to talk nonstop about video games. He did what he needed to do and turned on has satellite radio to channel 72, the Sinatra channel, and zoned out to the classics. His generation’s classics, anyway. The boys were in back, plugged into their PlayStations – or whatever they were called these days – and from time to time they jerked and twitched like they were having epileptic seizures as they dodged make-believe bullets or crazed demons. Every time one of them burst out in one of their convulsive outbursts Gertrude and Daisy dove under his legs, which made for interesting driving.

He took 91 down to Springfield, then hopped on the Mass Pike all the way too his exit, and as two in the afternoon came along he thought about his son sitting through that meeting with Dr Stone and Elizabeth’s sisters, and his mind drifted through all the implications of what might be uncovered – while he navigated the usual insane traffic on the turnpike.

Drivers in and around Boston weren’t called Massholes for nothing, he told himself each time a passing SUV cut him off to exit without signaling, and he couldn’t wait to get on the 146 to Providence. The closer he got to the Providence River the more at-ease he felt, and they made it to the boatyard about two hours after the sun set, just a little before six that evening. They stopped off for – what else? – pizza, before going to the boatyard, and his house. He was exhausted, but then again he was old. At least that’s what everyone told him.

Of course Hank wanted to show the kid The Blue Goose, and he couldn’t help but give in – even if it was almost nine at night by the time they had unloaded his old Blazer. He grabbed a flashlight from the drawer by the back door and they walked through fog just rolling in across the boatyard, and once he unlocked the door to the finishing shed he let Hank lead them in. He knew where the light switches were by now, and Hank flipped them on and then waited for the reaction.

Poor Huck. He had it bad.

He walked over to the hull and ran his hands along the boot stripe, then bent low to look at the centerboard aperture before walking aft to check out the rudder, and all the while he was reeling off the 28s vital statistics, everything from the displacement to length ratio to the sail area of the main. Bud was actually impressed.

“Do you think the owner would mind if we went onboard?”

“No, I don’t mind.”

“Not you, silly. The owner? Do you think he’d mind?”

Hank shrugged, then pulled out his key and handed it to Huck. “No, I don’t mind. Go on up.”

Huck’s double-take was textbook, the jaw-drop as satisfying as Hank had hoped.

“No way,” Huck cried.

“Way,” Hank replied, grinning.

“Well…fuck me…”

Bud laughed then found a chair and watched the boys go up the ladder and start crawling all over the deck. After a good half hour they disappeared down the companionway and the lights came on down below, and just then the phone in his pocket started chirping. Bud looked at the display and remembered he’d told Henry he’d call when they got in…

“We just made it, Henry,” he said before his son said a word.

“Traffic that bad?”

“We stopped off at Rocco’s for a couple of pies. Ya know, I forgot how much pizza an eleven year old can put down in ten minutes. It’s astonishing when you think about it.”

Henry chuckled. “I bet.”

“So,” Bud said, changing tack, “how’d the meeting go?”

“I don’t know what to say, Dad. I got so upset in there, so mad I was about to lose it. I felt sick, so sick that one of the docs gave me something. I don’t know how but I calmed down, but Dad, I had no idea people can be so evil.”

Bud didn’t say anything. Not yet.

“It was just awful, Dad. Anyway, I’m glad you didn’t come with us.”

“What does Doc Stone want to do now?”

“That’s the bad part, Dad. You aren’t going to believe this, but…”

+++++

After Huck was shown to his room, Hank walked down the creaky old hall to his own bedroom and straight into the bathroom. He leaned over the sink and stared into the mirror, hoping against hope that nothing would happen, and he was not disappointed. He sighed, brushed his teeth and then got ready for bed.

A few minutes later he heard a gentle knock on his bedroom door, and his grandfather came in after he answered.

“How’d your guided tour go?” Bud asked, his voice sounding tired, worn down by time.

“Are you okay, Grandpa?”

The old man shrugged, looked away. “Mind if I sit?” Bud said as he took a seat behind the little desk in the room. He switched on the lamp on the desk and then leaned back, gathering his thoughts, not really knowing where to begin. “Hank, I just got off the phone with your dad. We talked about his meeting at the hospital today, and it’s not good.”

“What does that mean?”

Bud looked down, steepled his hands over his chest and sighed. “I’m not sure I know where to begin, son, but maybe in the beginning. Your mother’s sisters were at that meeting, and they told the doctors what they experienced during, well, what had to be a pretty scary childhood. Your mom had a real hard time growing up, Hank, and she went through things that no child ever should. These things hurt her emotionally. Do you understand what I mean by that?”

“You mean her parents beat her?”

Bud nodded. “Yes, they did that, but they did other things too, things I can’t talk about right now because I’m so upset, but my feelings aren’t important right now. What is important is what your mother is feeling, and she doesn’t feel good about her life.”

Hank’s face turned full and pale as his eyes reddened. “What do you mean, Grandpa?”

“She’s really tired right now, like she’s been on a long hike up a mountain and she’s running out of steam, and she’s not sure she can make it to the top anymore. She’s thinking about giving up, Hank.”

Tears began rolling down both their faces. Bud was still feeling ill after listening to his son’s retelling of that meeting, and while he couldn’t bear to tell Hank any of those details he couldn’t in good conscience tell the boy a pack of lies and falsehoods. His family was dealing with the consequences of such things, of a life destroyed by falsehoods, and maintaining the wall of lies would only keep them all in darkness. He had always firmly believed that truth can only flourish in the light of day, that life withers and dies in the darkness of deceit, and he wasn’t going to change now.

“But Hank, here’s the thing. Your father is going to take your mom down to Boston tomorrow, and Dr. Stone is going to go with him. They’re going to try something, something really different, and if it works it could really help your mother cope with the things that happened to her. Again, when she was little…not now. So don’t think you’ve done anything wrong. Okay?”

“Okay, but what happens if it doesn’t work?”

Bud shrugged again. “Then we have to be strong for her, Hank. We have to be strong so…” – but Bud had to stop there. He couldn’t put the onus on the family, couldn’t leave his grandson with the impression that if only he had somehow helped enough bad things wouldn’t have happened. In so many ways now, Elizabeth’s fate was in her own hands and there was almost nothing her two boys could do but hang on tight and hope for the best, yet that powerlessness left Bud feeling worse than useless. For someone used to helping people build their dreams, this was a painfully uncomfortable place for him to be – but this was family. This was personal. And somehow he had to help make it right. “Hank, all I can say with any certainty is that you’ll need to be ready for the unexpected, but remember one thing for me, okay? You won’t be alone, and when you feel down about things, you need to come to one of us, either to me or Ellen or to your dad, and try to explain how you feel. Maybe we can get through this if we lean on each other, and by doing that maybe we’ll take some of the pressure off your mom. Got it?”

“Yessir, I think so. I guess, well, I wish I could talk to her, ya know?”

Bud nodded. “I know, son. Doc Stone will make that happen when your mom is feeling better.”

Hank nodded too, and he tried to smile but something inside was telling him that his mom wasn’t going to get better. Bud leaned over and put his hand on the boy’s head, then turned and went downstairs to get a glass of buttermilk – to go with his heartburn medications.

Hank lay in bed staring up at the ceiling, and he just couldn’t wrap his head around a world without his mother in it. What had happened to her? How could something that bad happen to someone so good?

+++++

After the meeting with Elizabeth’s sisters, her team in the psychiatric department decided to send her down to Massachusetts General, in Boston. She was transferred by ambulance, leaving Henry and Dr. Stone to follow in his car, and as he sat there with his thoughts, driving down the interstate towards Concord, New Hampshire, he found he was having a hard time concentrating on the road. There had been several snow storms the last few weeks, yet even so the roadway had been expertly cleared, so unless he strayed onto the shoulder the trip presented no real problem to him.

Dr. Stone was, however, another matter entirely. The woman was an expert interrogator, and he assumed she had been trained by the CIA. Or the KGB…

“So,” she asked at one point, “how’d you two meet?”

“I was putting some papers into the reserve reading file at Baker, and she was helping out on the desk that morning. I hadn’t dated since my wife passed, and I don’t think I planned to again. I guess we just sort of happened, like two particles colliding in a maelstrom, maybe.”

“So the girls are from your first marriage?”

Henry nodded. “That’s right. Liz didn’t want to wait, wanted kids of her own. Funny, my first wife didn’t want to wait, either.”

“It’s a biological imperative. To procreate, I mean.”

“I suppose so. It’s a wonder we’ve survived as a species for as long as we have.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Sometimes it feels like we’ve embraced chaos. Planning is verboten. Everything is just random chaos, so we’re creating a chaotic world.”