Ah well, here we are at another Christmas…and so…what else is there to do? I will wish you a very Merry Christmas, and hope the coming year brings a fair measure happiness your way.

I have a few pieces of music in mind for you today. I have been listening to Pat Metheny’s The Lore all week, a compilation of works spanning decades and that makes for a perfect backdrop to writing a story – or getting a turkey ready to roast. I have to assume it will work for reading a story or two, as well. If so, you might linger on The First Circle, It’s For You, or even Barcarole. The Beatles Now and Then keeps popping up in my thoughts, which takes me to George Harrison’s When We Was Fab. That, for no reason that I can discern, carries me right on over to River Man, by Nick Drake, which takes me to In Places On The Run, by The Dream Academy. If you really want to go all 80s on Christmas Day, nothing will do that better than A Mannheim Steamroller Christmas. If a 60s Christmas is more your thing, throw away your Bing Crosby or Nat King Cole and put on the soundtrack to A Charlie Brown Christmas. And have a sip of Drambuie for me, would you?

And now, let’s see where Hank takes us – this time.

The Blue Goose

Part Four

Winters in the Upper Valley tend to be bleak – in the extreme. The cold comes early in autumn and lasts well into spring, and because it is a valley the air does get very cold. Actually, really very cold. So cold that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers located their Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory there, on the highway leading north from Hanover, New Hampshire. The sky seems to turn the color of lead in November and then remains that way until summer. When the first snows arrive in late October, long after summer’s lush green veneer has given way to reds and golds, the snow drapes the landscape in chaste shades of white, and the blue hour that arrives each evening seems to welcome the coming holidays. Yet by the time Thanksgiving and Christmas have come and gone for the year, even the snow has changed. It has turned from white to dirty gray. Snow plowed from streets and highways lines the pavement in chest high piles covered in road salt and oily grime. Driving around the towns and villages of the Upper Valley becomes an exercise in emotional futility.

At least that was Judy Stone’s version of winter.

Her days were filled with an endless parade of professors and students and desperate housewives coming to talk to her about the endless fugue of life in this gray-sheathed void of a town. She wrote out scrips for anti-depressants at the end of each appointment, and it seemed like the longer winter endured the deeper her patients’ depressions became. Yet every now and then she took on a new patient that broke the cycle. Someone who was profoundly ill. And right now that someone was Elizabeth Langston.

She had just spent the entire day at Mass Gen, on the third floor of the Wang Center in their psych ward, observing Elizabeth. She had noted, as her other physicians had, the sudden, dramatic improvement in her mental state after treatment, only to look on helplessly as an immense black hole returned and swallowed her whole. Within two hours of her ninth electro-convulsive therapy session, Elizabeth slid deep inside winter’s shades of blue and gray, and she did not return. Judy stayed until five in the afternoon and all afternoon she had watched the veil return, watched the light fading from Elizabeth’s eyes.

This descent was hard to take, and all the more so as Stone had so little frame of reference.

Elizabeth wasn’t simply manifesting severe depression; no, there were elements of a psychotic break interlaced within this depression, but ECT should have knocked them both back more than it had. Her delusional architecture, this thing about her son drowning and being saved by his pet goose, almost fit the circumstances. Almost, but not quite. Hank drowning might symbolically represent her own sense of drowning, her own psyche being smothered by her father’s predations when she was Hank’s age. But the goose? What might the goose represent inside this delusion?

She walked back to her car in the physicians lot then fought her way through Boston’s rush hour congestion on Charles Street, finally making it onto Interstate 93 north towards Concord. She had a good 90 minute drive back to the Upper Valley, and she had to admit that winters up here were really getting to her. The unrelenting grayness, the cold damp grayness of this place was beginning to feel more than oppressive.

A goose? A blue goose?

Where did this blue goose come from? Was it a mutation, or was it a natural variation that occurred with some regularity? Emily might know…but did it really matter? The goose probably meant nothing, at least it did if it was just another feature of Elizabeth’s delusion. If that was indeed the case then Hank’s drowning had to represent something about her own childhood…but if that was the case then why did Elizabeth keep retreating back into the confines of a childhood delusion? What was keeping…no, what was holding her there? Why would she keep returning to the same delusion if not because she found comfort and solace there? But…why wouldn’t taking care of her children bring her comfort?

Her thoughts bounced between these evolving permutations all the way to Concord, but once she was on Interstate 89 heading towards Hanover it started snowing. Heavy, wet snow. The road’s surface looked black, slick and fathomless, and soon enough the pavement began disappearing under a veil of fresh, white despair.

“You need to slow down now,” a distant voice said.

She flinched as the words washed over her, just as she recoiled from their specificity.

The radio wasn’t on. The voice the car sometimes used to sound an alert didn’t sound at all like the voice she’d just heard. And she’d heard it, too. This wasn’t some kind of dime store hallucination. This was real. Something, or someone, had just told her to slow down…

She put both hands on the wheel and slowed down to 55 miles per hour, then 50…

“You need to slow down more,” the voice said. She jerked around, looked in the rear of her Subaru and saw there was nothing there.

“More. Slow down more. There’s an accident up ahead.”

“Alright!” she shouted. “Enough! Who the hell is this? Where are you?”

“You’ll be fine now, just stay to the right as you crest this next hill. Two people are hurt, so stay out of the road when you go to help them.”

She recognized the voice now. It was unmistakable.

It was Henry Langston. She knew that voice…

And as soon as she crested the hill she came upon several cars and a jack-knifed moving van sprawled across the highway, a steady stream of smoke and flames coming from one of the cars. As she rolled to a stop she could already see that several people had been seriously hurt, and she pulled out her phone and called 911. She made sure her jacket was zipped then grabbed her black bag and went out into the blinding snow…

+++++

By the time Judy made it to her house in Norwich, Emily was almost frantic.

“What happened to you out there?” she cried, looking at the clock on the wall behind Judy. “It’s two in the morning, for Christ’s sake!”

So Judy told her. Everything. About Elizabeth, about the accident. About the voice that had forewarned her. Henry’s voice.

“Oh, that’s just great!” Emily moaned. “Ladies and Gentlemen, meet Judy Stone, the hallucinating shrink!”

Judy smiled. “He told me to slow down, Em. And that over the next hill there was an accident, and that it was a bad one. But here’s the thing. If I hadn’t slowed down when I did I would have plowed into all that wreckage. It was a chain reaction accident, Em, and how the hell did he know that…?”

“He didn’t, Judy, because he wasn’t there. Are we clear on that? He wasn’t there, so…”

The doorbell chimed.

Judy looked at Emily, who was dressed in her bathrobe and slippers, so she shrugged. “I guess I’ll get that,” Judy sighed.

“Are you out of your cotton-picking’s mind? It’s two in the morning, and you’re going to answer the door?”

“It’s him.”

“It’s who?”

“Henry. I know it’s him.”

“Oh, well then, why not? Sure, let’s just go with it and say it is. Then what?”

Judy shook her head and walked over to the door and looked out the peep-glass and then just shook her head as she unbolted the door.

And of course in walked Henry Langston.

Emily Stone pursed her lips and took in a deep breath, then took off for her bedroom.

“Are you alright?” Henry asked Judy.

“How did you do that?”

“I could tell you…but I feel certain you wouldn’t believe me.”

“Go ahead. Try me.”

Henry sighed. “Damn, I thought I knew what I wanted to say, but now I’m coming up empty.”

Judy took him in hand and towed him into the living room. “Sit, please. You feel like coffee?”

“Might as well. I’m sure not going to sleep any tonight.”

She went into the kitchen and put a pod in the coffeemaker and got two cups ready, then as soon as Emily reappeared – now dressed – she got a third cup ready to go. When she made it back to the living room she handed a cup to Emily and another to Henry, then she went back for her own.

But Emily wasn’t having any of it. No, not at all.

“Judy tells me you warned her about some accident on the highway tonight?”

Henry nodded. “I did. Yes.”

Emily’s eyes narrowed. “Care to tell us how you pulled that off?” she asked, as Judy came into the living room and sat.

“I need to ask Judy something first.”

Judy shrugged. “Sure. Why not?”

“What did Liz tell you today, after the procedure?”

“I don’t know, Henry. Why don’t you tell me?”

He nodded, looked down and steepled his hands. “She saw Hank. Hank and Gertrude, right?”

Judy flinched again. “How could you possibly know that?” She looked at Henry, then at Emily.

Emily Stone was pale now, and suddenly didn’t feel good.

“Did she tell you that Gertrude was with him?” he asked again.

“Yes. Why?”

“Because we can’t find her. The goose, I mean. She was with Hank down at my father’s house, and then…”

“Down in Rhode Island, right?” Judy said, confused.

Henry nodded. “Yup. Down near Newport.”

“On the water? Is Hank sailing?”

“Yes, but he’s not there right now. He’s – elsewhere.”

Emily’s brow furrowed. “Sailing? In this weather? Henry, that’s a nor’easter blowing out there! You’re not saying your boy is out sailing in this storm…?”

“Not this one, no, but Judy, Liz said the goose was with Hank, right?”

She nodded. “She did. Now, you want to tell me how you knew that wreck was on the highway?”

Henry downed his coffee and stood. “Sorry, but I’ve got to run.”

Judy stood and blocked his way, and she was shaking her head. “No, not until you’ve answered my question.”

Henry sighed. “I’ve got to get down to Newport, now. If you want answers, you’ll need to come with me.”

Emily stood too. “If she goes, I go.”

Henry shrugged. “You better pack a suitcase. We might be gone for a while. And, while I’m thinking about it…do you have a good medical kit you could bring along…?”

“My bag. Will that do?”

“Could you get a couple of bags of saline and maybe some D5W, and bring a couple of sets to start IVs.”

“Uh…why?” Judy sighed, suddenly feeling small.

“In case we need to set fractures or something.”

Judy put her hands on her hips, her lower lip jutted in a display of incredulity. “At your father’s house? Really?”

“And maybe put on some clothes you don’t mind getting…soiled,” he added – with a sly grin.

Judy looked at Henry, now totally confused, then she looked to Emily for reassurance, and finally she just shook her head, not at all sure what to do.

So Emily went to get all the supplies Henry had asked for, even if some of the things she brought along were meant for dogs and cats…

+++++

Judy could hardly keep her eyes open; Emily was sound asleep by her side, snoring gently. Henry was behind the wheel, the two women were in the rear seat of his Land Rover and Hank’s dog Daisy was sitting up front beside Henry.

She looked out the window, at the unremitting grayness of the passing Connecticut landscape. There was snow on the ground here too, of course, but nowhere near as much as there was in Norwich, yet it just didn’t matter; one foot of snow, or ten, the gray was the same. Relentlessly empty, and she thought the bleak gray-black of sunrise was worst of all. ‘Why am I so depressed,’ she asked as Henry passed another snow plow grinding along over in the far right lane. ‘Ya know, I don’t think I’ve ever been so depressed. Is it Henry? Does he depress me? Or is it…Emily?’

She and Emily had started out as friends but after a few months together the relationship had changed into – something else. Their time together had at first turned soft, then over a long weekend more intimate, yet in truth it had been a gradual thing, they’re coming together. Emily had told her once that she had never thought of herself as gay or straight…that she just…was. She had never been physically attracted to anyone, and had never wanted to share her life with…anyone. She had always been quite comfortable being on her own and she told Judy that between her patients and her staff she simply had never felt alone.

That had all changed after she met Judy. It wasn’t an overwhelming attraction, Emily had implied, it was more a yearning for connection and, ultimately, the comfort of knowing someone was at home waiting for her at the end of the day. Funny, Judy thought, how things like that come about. Judy was a workaholic and sixteen hour days were the norm. She came home and had a snack then went to bed, while Emily usually caught up with her veterinarian journals, often reading past midnight. Yet the brief intimacy they shared had flared brightly but had simmered unattended in the years since.

Yet Judy now felt herself slipping into this bleak, gray landscape, her sense of self disappearing inside what was beginning to feel like a soul-sucking icy-gray landscape of barren trees and broken dreams. She knew her life looked great from someone standing on the outside, but from in here she felt like she was circling the drain. When she thought about it, every one of her colleagues in the department felt pretty much the same way…like dealing with other people’s emotional lives, and the endlessly complex dead-end emotional landscapes her patients found themselves in, was sapping her own sense of self, draining her appetite for life. And Emily wasn’t helping matters. Emily wanted physical intimacy, and Judy was beginning to realize that she wanted nothing to do with her, not in bed, not even around the house. So, had she found her very own dead end, or was she just drifting through the doldrums of middle age? Could they rekindle what they’d once had, or was the end in sight?

Or, as she had long felt, did it really matter anymore?

Some people seemed born with a happiness gene, and then, she thought, there were the rest of us. The ones who called for appointments, looking for a way out from under the oppressive bleakness of another day.

Then there were people like Henry…who just didn’t seem to give a damn about happiness, one way or another. He was all about duty. Duty, and honor. To his family. Was that the key? The secret to lasting happiness? Was keeping your nose to the grindstone and making sure your family went on into the future…was that it? Because if that was indeed true…well then, she was fucked. Family had never seemed all that important to her, and now more than ever.

The landscape outside this car bore all the hallmarks of futility, too. Of futile lives doing…

“Stop it!” she sighed, bunched up inside like she wanted to cry.

“Stop what?” Henry said.

“Oh, nothing. I was just thinking…”

“And you need to stop? What’s got you down?”

“What makes you think I’m down?”

“Well, for one thing, the frown, no, it’s more like a scowl, on your face. The same face I put on after after a really bad day in the classroom.”

“Really? Physics professors have bad days? I had no idea…”

“Oh, sure. Try teaching remedial calculus to someone who made it through high school with inflated grades and who scored a few points with the admissions committee by being a legacy ‘with a bright future’… That’s about half my students, by the way. They’ve never heard of a quadratic equation and never heard of Pythagorean geometry, and they show up in a class where three years of calculus used to be the norm and before they know it they’re failing. But Judy, that’s when the real fun begins. The calls from their father come first. If that doesn’t work, the department chair calls next, then the Dean, and before you know it the president of the college is holding on line 2. ‘You can’t flunk so-and-so’s kid, Henry! It’ll cost us millions in future endowments!’ That’s when I reach into the top drawer of your desk and pop a Maalox, then come to the conclusion that you are in real need of a career change…”

“I guess we all have our problems.”

“That’s about all you deal with, isn’t it? Other peoples problems, I mean.”

She nodded.

“And that’s what you were thinking about, wasn’t it?”

“So, you’re a mind reader, too?”

He chuckled. “I have two daughters, so of course I read minds.”

She smiled. “I wouldn’t know.”

“Oh, so now I hear regret, too. Judy, are you doing okay?”

“Sometimes it feels that way. Regret, I mean.”

“You could adopt?”

“I suppose, but that’s not the same, is it?”

He shrugged. “I don’t know about that. Raising kids is all about the love. Everything else flows from that.”

“Is that the voice of experience talking?”

“No. That’s my parents talking.”

“That’s what they…what you took from them?”

“Yup.”

“You’re lucky, Henry. You don’t know how lucky you really are…”

“And that’s why I said what I said, Judy. Any problems you have with kids…you just have to handle the situation with love. Or maybe put it another way. Do unto others usually works out for everybody, but with your kids you have to do that with love in your heart.”

‘And you’re naive,’ she wanted to say. Life can’t be boiled down into such a simplistic outlook. That was not just unrealistic, it could lead to lasting pain and damage. Or…am I wrong…? She saw his eyes in the rearview mirror – but he wasn’t looking at her. He was looking at Emily right now. And she just knew he was reading her mind. He had to be. How else had he…spoken to her last night, on the Interstate?

She didn’t even want to admit that something as crazy as that had happened, yet it had. And she wasn’t finding any answers right now, especially not from him. So far he had evaded her every question, and adroitly, too. Just like he had done all this before, and probably more than once. Yet he was promising resolution, wasn’t he? All the answers to her questions. Down here, at his father’s house…at his family’s boatyard…by the sea…

+++++

And, of course, Henry’s father was out front, waiting. For them. But…how did he know they were coming? Henry hadn’t called, or had he?

But that blue goose was out there with the old man, too. Gertrude? Her name was Gertrude. ‘But…who names a goose Gertrude?’

Bud went right to Emily’s door to open it, and his smile was warm and welcoming – yet there was something more in his eyes. Was that a wry – if knowing twinkle…? Like someone in on the joke, perhaps?

Henry went around to get Judy’s door, and he held out his hand to help her down onto the snow covered driveway, and she saw the same knowing twinkle in his eye, too. What was going on? What were these two up to…?

“Henry? You look like you could use some sleep.” Bud shook his head as he shrugged, going around to get luggage from the year of the car. “You’re too old to pull all nighters, you know?”

“Et tu, Brutus,” Henry replied.

Bud had a good laugh at that. “Well played, Julius. Well played.” Bud turned from Henry and started for the house – but as Judy watched all this, the goose flew up and landed on the old man’s shoulder – and she stayed there as he walked across the boatyard’s parking lot and into his house.

“A tame goose?” she muttered under her breath. “Why not, ya know? Why the fuck not…”

Henry heard that and chuckled. “Sometimes nothing’s as it first appears,” he said – to both Emily and Judy.

“I thought your dad was married?” Emily asked, wondering why Bud was alone.

“He is. My mom is staying with Hannah and Jennifer while Liz is away, so don’t be shocked if the kitchen isn’t gleaming.”

But of course the kitchen in Bud’s house was gleaming, ready for a general inspection by the the ship’s commanding officer. He had pancake batter whipped up and bacon draining on paper towels and was already working the griddle, pouring cakes and warming plates.

Judy looked around the house – yet more by way of professional assessment than idle curiosity. One of the first thing that happens to people experiencing a mental health crisis, whether acute or chronic, is the ability to take care of themselves – and their surroundings – and this shows up as anything from clothes scattered one the floor to dishes piled up in the kitchen sink…

Yet this house was spotless. Much of the furniture in the house looked like it had been built on-site, and everything had a distinct nautical flair, but especially this kitchen.

“What kind of wood is this,” Emily asked as she ran a hand over the grain of a cabinet door.

“Burmese teak. The boys and I made these cabinets back in the 70s, before all the rampant deforestation began. There’s not a more elegant wood in the world, not when it’s maintained correctly.”

“Did you varnish it?” she asked.

“Hand rubbed with teak oil, about ten coats when they were first built, and I hit ‘em with lemon oil every month or so. The trick is to oil all the surfaces, inside the cabinet and out. Teak will literally last forever if you do that. Something to do with the crystalline nature of the fibers.”

Henry chimed in now. “Do you still bring clients in here? To show them the woodwork?”

“Oh, absolutely. This is the same cabinetry we put in all our boats, and when a buyer takes one look at this work, well…they’re sold. The stuff going in new boats these days is all veneer cut on a computer controlled milling machine. Those boats have no soul, and that crap will fall apart in a year or two.”

Judy opened a cabinet door and looked at the workmanship, guessing it took someone a few hours just to assemble this one door. She was wrong. It often took three people an entire day to cut down the raw lumber, plane it to perfection, then measure and cut – before assembly even began. After that, fitting the hinges and routing the slides, then getting the first two coats of oil on. Every joint on every bit of woodwork on one of Bud’s boats was glued and screwed, and there wasn’t a nail gun anywhere to be found in his boatyard.

“How many carpenters do you have working for you?” Judy asked.

“None. Everyone here works on every part of a boat during the construction process. We don’t build twenty boats a month, we build twenty a year so there’s no way to have teams with different skillsets. Funny thing, too. Most of my guys have been working with us for around twenty years, a few a lot more than that.”

“So any one of your employees can make furniture of this quality?”

Bud nodded. “Yup. And an hour later he – or she – might be wiring a circuit breaker panel or welding stainless steel. With a low volume business like this one, there’s no way to employ hundreds of people, and when you’re focusing on build quality there’s no way you can outsource critical components, so when we take someone on here they’re essentially starting a years long training program, learning all the skills they’ll need to do the job.”

“How many people do you hire every year?”

Bud chuckled. “Oh, maybe one person every three or four years, Ms. Stone, but it’s probably less than that. In the last twenty years no one’s quit or moved on to another job. We replace people only when they decide to retire. If somebody gets dissatisfied with the conditions here I like to find out why and fix the problem.”

“So you know everyone’s name?”

Bud laughed at that one. “I know their wives names, their kids, their dogs. I know most of their birthdays, and I know their retirement goals, too. It’s a part of my job to see that my guys retire with dignity, that they can go out there and do the things they’ve wanted to do.”

“Amazing,” Emily sighed.

Bud shrugged. “I’m not going to preach, not going to say that’s the way it should be, but it is the way I was taught to run my business, and it’s the way I’m teaching Hank to treat the people here.”

Judy crossed her arms. “Speaking of Hank, Mr Langston. Where is he?”

Bud looked at his son, then at the pancakes on the griddle. He turned one then shook his head. “Damn near burned that one,” he sighed. “Oh, well, got to concentrate better…”

Henry spoke next. “I told you; he’s out sailing right now.”

“Surely not around here?” Emily said. “Not in this blizzard…”

“No, not here,” Bud sighed. “I believe he’s somewhere on the North Sea, about a hundred and forty miles east of Aberdeen.”

“You mean he sailing off the coast of Scotland? In the middle of winter?” Judy snarled.

“It’s not winter when he is,” Bud said with a grin.

“Not winter there? How is that ev…wait a…wait a minute. You said when he is, not where he is. What’s that supposed to mean?”

Bud turned to Judy and shrugged. “So, will two pancakes do ya, or are you a three pancake kinda gal…?”

+++++

There was a book on the table in the breakfast room off the kitchen, but Bud and Henry ignored it while they ate. Judy fidgeted, still not sure what these two clowns were up to but absolutely sure they were about to play a joke on them. And that crap about fractures and a medical kit…? These two were world class con-artists!

Then Bud stood and began clearing their plates from the table, and it seemed to Judy that Henry joined him automatically, picking up their plates and taking them to the kitchen, and then working together the two cleaned the kitchen and got the dishes in the dishwasher. Very practiced, very much a team effort. And with nothing said between them.

But when the two men came back to the table their demeanors had changed. They were no longer pleasant. Bud was no longer smiling. Henry almost looked somber – even though he had to be beyond tired. But they both sat down, then Bud picked up the book in the center of the table.

“This is a logbook from a voyage my great-great-grandfather made in 1821 on a ship called Pegasus, and he went from Hull, on Britain’s east coast, to Bergen, in Norway, then on to the Hanseatic city of Lübeck, which Henry, my relative, refers to in the log as the City of the Seven Towers, although he – infrequently – refers to it in the German, Stadt der Sieben Türme. Incidentally, Lübeck was called this because of seven large church spires in the main part of the city, not that this tidbit is of much relevance right now.

“Pegasus was carrying goods between these cities, and after leaving Lübeck, the ship returned to Bergen before sailing south for London. Not quite halfway into this last part of the voyage, the ship was overtaken by a large storm system, which Henry describes in these pages as a white squall, which is a type of line squall. These storms move across the sea like a hand pushing a wall of wind and water at high velocities, and when they first appear sailors see only this wall of white mist approaching. The storm hits with extraordinary strength, and captains who are aware of these approaching storms get all their sails down, then prepare the crew to prepare for extreme angles of heel, which often occurs as the storm hits. Large sailing ships were most effected by these types of storms because of the windage created by their large masts and yards, and of course all the rigging associated with holding up these spars. When such a wind catches a sailboat unawares the consequences are immediate, and usually lethal; when an knowledgeable skipper notes the storm’s approach and is able to adequately prepare his ship before the storm hits, it is possible to survive one of these storms.

“I’d like you to read the day’s entries in this logbook, made on the day when Pegasus encountered such a storm, then we’ll go and take a look at the real life consequences of one of these squalls.”

Bud passed the log to Judy, and the book was already open to the page that began the day’s notations.

Judy held the book open and Emily scooted her chair close to Judy’s so they could read the passage together. It took them no more than a minute to get through Henry’s stilted wording.

“What’s a topsail?” Judy asked.

“Ah. On a square rigged ship, the sails on the main spars are furled and flown from a yard, a horizontal spar attached to the spar, or mast. The topsail is flown from the highest yard on a spar.”

“And a gaff?” Emily asked.

“On the mizzen mast, the mast furthest aft, a mainsail is usually flown, as opposed to a sail unfurled from a yard. A mainsail looks like that,” Bud said, pointing to a painting on the wall of a Langston 43. “It’s the tall, triangular sail behind the mast. A gaff rigged main is trapezoidal in shape, and the gaff is a short spar that holds the mainsail aloft from above the sail, and it is adjusted vertically to change the shape of the sail to suit the current condition of the wind. By the way, the gaff is attached to it’s mast by an iron ring.”

Judy shrugged. “Okay. What’s all this have to do with Hank?”

Bud stood, then so did Henry. “Let’s get your gear,” Bud said, suddenly smiling again, “and take a little trip…”

Henry carried their duffels to, of all things…a bathroom. Bud stood by the sink with Gertrude on his shoulder again, and as the women came into the small room they looked seriously unsettled. Judy was now expecting the worst…

“Now,” Bud said, “if you wouldn’t mind, have a look in the mirror – and tell me what you see…”

+++++

For some reason, Judy looked into Gertrude’s eyes. She was still on Bud’s shoulder, but she had just caught the goose staring at her…

And so, of course, she stared in the goose’s eyes.

And so, into the blackness she saw inside those eyes…

…and then she felt her world collapsing…

…she had no idea why, but for a moment she thought she was being swept away then inside a black hole, that she had been caught in the outer reaches of the intense gravitational pull and was now swirling away into oblivion, yet dissolving inside Gertrude’s eyes…

And a moment later she felt herself adrift, adrift in endless black. Not just dark, but an infinite black. And she wanted to scream – but who would hear it if she did? This was absolute nothingness. Infinite nothingness. And she was alone, inside…nothingness. And then she realized she had been afraid of just this moment – her entire life.

She drifted there for days, or perhaps weeks. Or maybe it was just a minute.

‘Time can’t exist in nothingness. But…neither can I…’

And that thought scared her most of all.

Then…a sound.

Like a hand on a doorknob. Turning a doorknob.

A door opening. The creaking of an old, disused wooden door swinging open. A sound as lonely as nothingness, yet in a way full of lingering hope.

But there was no light, no form in the darkness. Only nothingness…

…yet she heard footsteps. Footsteps in this darkness, in this infinite nothingness.

Then…a man. An old man. Very old. And yet he looked…familiar.

Like an old Jewish man, almost like…Albert Einstein, or the actor who played the professor in that movie…the one with Klatu and Gort…and Patricia Neal…

She remembered the movie, and the way the Patricia Neal character reacted when her boyfriend acted out of greed to betray her, to betray Klatu, and she remembered feeling that way about her own husband. All he’d been interested in was money, and all the things he’d talked about, what he wanted to do with her after they were married, had turned out to be a lie. He’d been a good liar, too, yet a liar with a black heart. As black as nothingness.

She’d been in her fourth year of med school when he died…

“And you came to his funeral,” she said to the man standing there inside her nothingness. “Didn’t you?”

“So. You remember me?”

“You were my grandfather.”

The old man smiled. “It’s nice to be remembered.”

“You can’t be real.”

“Oh? Why not?”

“Because you died. I was there. I was with you when you died.”

“I remember when you whispered in my ear. What you said to me. ‘Thanks for always being there.’ You don’t know how much those words meant to me.”

“I always loved you, you know? Even more than Dad.”

He smiled. “What are you afraid of, Judy?”

“This. Darkness. Nothingness.”

“Is that so?”

“What? What do you mean by that?”

He smiled. “Isn’t that what you call resistance? Changing the subject. Words used to conceal your real answer, the real truth. Do you remember, when you were four years old when Jamie Weiss took your tricycle away from you and hid it in his parent’s garage. Remember how much you hated him?”

“He was a bully. Everyone on our street hated him.”

“You were afraid of him, too, weren’t you?”

She nodded. “Yes. I was afraid.”

“And you’ve been afraid of bullies like Jamie ever since. Is that why you’re afraid of Henry?”

“Maybe.”

“Is he a bully?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Why? Because he’s a man? And every man you’ve ever known has been a bully?”

“Maybe?”

“Judy, isn’t that answer just another form of resistance?”

“How could you remember that? With Jamie. You weren’t even there?”

And in an instant the old man resolved into a woman, a middle aged woman in a gingham dress, wearing an apron.

“Mom? Mom, is that you?”

“You came home with a strawberry on your knee that day, too. Do you remember? When Jamie pushed you down, after he stole your tricycle?”

Judy nodded as tears started rolling down her cheeks. “You made it all better. You always made it all better. You always made the pain go away.”

“You always felt pain,” her mother sighed. “Even other peoples’ pain.”

“I know.”

“But it wasn’t really pain, was it? It was fear. You were afraid.”

“I was. Yes, I think I’ve always been afraid of people.”

The visage of her mother wavered in the nothingness and then her grandfather reappeared.

“There, there. Was that so hard?”

“Who are you?” Judy asked.

“Who do you think I am?”

“Are you…God?”

The old man looked away, then shook his head. “Are you God?” he asked immediately?

“Me? Of course not!”

“Then how could I be God?”

“What?”

“You look inside a goose’s eye, just as you might look inside a mirror, and what do you see? Do you see God?”

“No. I see myself?”

He smiled again. “Is that something to be afraid of, Judy?”

“My own reflection? No, of course not.”

“Then don’t be afraid. Go on now, because it’s time to join your friends…”

The old man faded and another appeared. It was Bud again. Bud Langston, and he too was smiling at her…

“Are you ready now?” he asked, holding out his hand.

She reached out and took it. His flesh was warm, reassuring. Human. His grip was firm, yet friendly.

“I’m afraid,” she said.

“Sometimes life is scary, sometimes you meet mean people, but that doesn’t mean you need to be afraid.” He squeezed her hand gently as his eyes lingered in hers. “Should I take you back?”

“Back?”

“To the house. Or we can go on and join Emily and Henry.”

“Would you…would you stay with me, please?”

“Of course.”

She felt a gentle tug before the feeling of dissolution returned, before the event horizon reasserted itself, then she was inside a large sea cabin. Emily and Henry were standing there, and Em looked like she was in a state of shock. Her mouth was wide open, her body was rigid – yet her eyes were scanning her surroundings. Suspicion filled her heart, too. Judy could feel it…

And so Judy looked around too.

She saw a large desk, a few cabinets and a bookshelf. Windows, leaded glass in an arc, a gentle arc, across the back wall. She let go of Bud’s hand and walked to the windows, and then a part of her wanted to recoil from what she saw. Something like a hand, perhaps, or her grandfather’s voice. She saw the sea, which meant she was on a ship, and that the ship she was on was battling rough sees. She looked out, saw a raging wall of white mist approaching, then she heard shouting up above, like up on the deck of this boat.

Bud came to her again.

“We’ll be heeling now,” he said gently, almost warmly, “so get ready.”

Muffled cries from above, men shouting huzzahs! as someone did something heroic, and while she opened up her medical kit she realized that Henry was no longer with them…

But a minute later Hank and Henry returned, carrying a completely disheveled rodent of a man who smelled like nothing she had ever encountered before. Dirt and sweat, filth ground into the flesh, no bath in weeks, maybe months. Maybe not ever. His right ankle a mess. The flesh over his tibia had been abraded and now only bone showed. Bone, and blood.

And then her training took over. Emily’s did as well.

“Put him here, on the table,” Judy said as she went to her kit and found a bottle of sterile saline.

Emily was at Ian Nicholson’s side, examining the bone, flexing the tendons, ignoring the stench and the boy’s pain.

Hank was holding Ian’s hand, telling him it would be alright soon, and Henry and Bud quite literally disappeared. Hank heard his great-great-great grandfather calling out and he remembered his place was up on the poop deck to help at the wheel, but before he left he looked over at the two physicians.

“There’s a big blow coming. When it hits, find something to hang onto.”

Judy looked up and nodded, then opened a bottle of Betadine and poured some on Ian’s wound. She daubed it carefully, removing all the splinters and debris she could see in the dim light, poring more saline onto the tattered bits of flesh hanging beside exposed bone.

Emily was preparing a syringe, a tetanus shot, and she took an alcohol swab and wiped Ian’s shoulder, then pinched his skin a little before she inserted the needle. She put that syringe down then hit him with a small dose of morphine and almost instantly Ian stopped crying and screaming; Judy was examining the wound, trying to see if there was enough skin left to suture – when the sound of the wind assaulting the ship suddenly changed…

‘…tie yourself to something!…’

She heard the man’s voice shouting out the alarm and she looked out the window and saw the white wall was now just a few hundred yards away…

“Let’s get him on the floor,” Judy said to Emily. They lifted Ian and she couldn’t believe the boy weighed so little…perhaps a hundred pounds but she doubted even that. Half his teeth were missing, his fingers were a series of calluses, and the boy’s hair was a greasy mess of tangled red strands.

Then the wind hit.

The moaning sound in the rigging changed to a screaming howl. The back of the ship seemed to yaw, hard, to the left, and a moment later the heeling motion grew noticeable, then frightening. All three of them began sliding down the floor, down to the wall on the left side of the ship. She was on her back as she slid and her head hit the wall first, then the boy slammed into her, knocking the wind out of her. She saw Emily tumbling, bouncing off a chair as she fell on her way to the wall, then the chair followed and crashed into her…

And yet, she wasn’t afraid.

That was the one thing that entered her mind.

‘I ought to be afraid…but I’m not. I need to take care of this boy…’

The ship seemed to lay on it’s side for minutes but soon she was righting and the resulting chaos was almost as bad as when the wind hit. Men were screaming orders, she heard bare feet running on the deck overhead as men ran to carry out orders…then the sounds of water rushing and waves crashing and winds howling merged into one layer of chaos…

The floor leveled and she grabbed the boy and carried him over to the table. She lifted him – by herself – and got him up on the table. Then she reached into her bag, pulled out a penlight and looked into the boy’s eyes. The morphine had him now, but his pupils were reactive so she moved down to his leg again. More crap to debride, more saline, then more Betadine. Pull the flaps of flesh up, hold them in place with steri-strips, then lidocaine into the margins. Probe, make sure no debris is hiding deep out of sight. More saline. Emily by her side now, holding the penlight so Judy could see better.

“I think I’ll try 3-0 ethicon,” she sighed.

Emily pulled out a small steel tray, still wrapped and sealed after going through an autoclave, and Judy gloved-up and took the hemostats Em handed her. She was surprised how easily it came back to her. She had enjoyed her stint in the ER more than anything else she had done during her internship, but she had been – afraid – of going into emergency medicine because it would keep her away from home. Psychiatry, she remembered, would interfere less so she could be home on a regular schedule…and she had been afraid, always afraid…

It took her maybe five minutes to sew up Ian’s leg, then she took a four by four and wiped it clean again, wiping away all the remaining traces of blood and fleshy debris. Emily helped her wrap the wound in gauze, then they wrapped his lower leg with an ace bandage before Judy worked a compression sleeve over her work.

“That ought to keep everything in place while he heals…” Judy said as she rummaged around in her kit. She found a syringe and a vial of broad spectrum antibiotic and Emily cleaned off a spot on the boy’s flank, then Judy gave him the shot. “He’s never had an antibiotic before,” she said as she looked up…

“It ought to work even better,” Emily added.

“You know…I’m not afraid anymore. Isn’t that strange?”

“Afraid? Of what?”

“I don’t know…maybe my life.”

“Really?”

“Yes, I know it sounds strange. It’s kind of hard to put into words, but I’m tired of being afraid…so I’m not going to be. Not right now, not ever again.”

“Is that a bad thing, Judy.”

“And I’ve never loved anyone, Em, except maybe my grandfather.”

“So, not even me?”

“I don’t know what I feel about you, Em. Maybe it’s like love but I’m not sure what it is, not really.”

Emily didn’t know how to react to this. What to say. How to feel. But one thing entered here mind: “Henry? Do you love Henry Langston?”

“Him? Gawd-no! Are you kidding me?”

Emily sighed. “If he wasn’t married I’d go after him. In a heartbeat.”

“Really?” Judy said, shocked. “He turns you on?”

Emily smiled. “Yup. Big time.”

Judy shook her head as she grinned. “He seems like a real stick in the mud to me. Bland. Like a physicist, I guess. Lost in his own universe.”

“Those guys always got to me, I guess. Cerebral. Made me weak in the knees, too.” She sighed, looked around the messed up cabin, the furniture scattered everywhere. “You were that way once, ya know?”

“Was I? Is that what attracted you?”

Emily nodded. “It’s funny, I guess – in a way. We’re here right now because of a lost, injured goose. A blue goose, at that. I wonder about things like that, sometimes.”

“That’s just life. You never know how it’s going to come at you, do you?”

“I always thought we’d be together, Judy. That we’d make it, ya know?”

Bud appeared, and he looked around once and shook his head. “Not as bad this time,” he sighed. “Well, are you girls ready?”

“Ready?” Emily asked. “For what?”

“You don’t want to stay here, do you?” he asked, pointedly looking at Judy.

“I think I do,” Judy said.

“You’re not…afraid?” he added – with a smile.

“No. No, I’m not.”

“Okay. Well, tell Henry that you’re a friend of mine and he’ll understand.”

“Henry?” Judy said.

“My great-great-grandfather. Sometimes we just call him Henry the First. It’s easier that way.”

“You come her often,” Emily said mockingly.

“Oh, yes, all the time. Whenever I…lose my way.”

“What is this place, really?” Judy asked, clearly confused.

Bud turned and looked at her, then he smiled and nodded. “What do you see when you look into a mirror?” he asked.

“Me. My reflection.”

Bud shrugged. “Well, it’s as simple as that. You’re simply looking inside yourself. And who knows, maybe you’ll like what you see.”

A split second later both Bud and Emily spun out of existence, at least existing in this space, and she was left standing beside this boy on the table. She looked at him, recognized his face. He had the same face as all the bullies she had ever known. Mischievous, devious faces, their smiles always too ready, their words too cunning for their own good. Too willing to intimidate, so unwilling to listen. To learn – how can you learn if you never listen? Really listen? Bullies are know-it-alls, and yet they never want to learn, do they?

The boy opened his eyes and lifted his head a half inch off the table.

“Who be you? The Captain’s lady, perhaps?”

She looked down at him and smiled at him easily. “Does your leg hurt?”

“No,” he sighed, raising up on his elbows and looking at the bandaged wreckage down at the other end of the table, “nothing hurts.”

“It will in an hour, so you might as well rest right now.”

“What happened to me?”

Judy shrugged. “I don’t know. I didn’t see what happened.”

“You talk funny, like. You ain’t from Hull, is ye?”

“No. No I’m not. Are you?”

The boy nodded. “Me mother works at an estate outside the city proper. I stayed with her there until I was of age, then I shipped out with the Captain.”

“Captain Langston?”

“Yeah, that’s right.” He looked at her, at her green surgical scrubs. “What’s DHMC?” he asked.

She realized the hospital’s logo and information was printed on the pocket over her left breast and smiled. “That’s the name of the hospital where I work.”

“Oh.”

“You better to get some sleep. I’ll be down to check on you in an hour.”

She turned and walked over to the door then walked down the heaving corridor, bouncing off the walls until she made it to the next door. Once she figured out how to open this door she stepped out into pure bedlam.

The boat’s rigging was a shambles and scattered all over the deck. Men were already sorting it out, some on deck but more up in the rigging that remained, and she heard someone calling her name.

Hank. Hank Langston. It had to be him.

She turned and saw a tall, thin man with searching, peregrine eyes locked onto hers, so she waved and made her way up the four steps to the poop deck, stepping over ropes and lines and pulleys while trying to keep her balance on the heaving ship. She confronted a huge gap at the railing there, as it had to be twenty feet of wide open space to reach the captain and the ship’s violent motion made walking almost impossible. Fear reached out for her and she felt herself falling away…

Then she steeled herself and walked across to him as if she was out taking just another Sunday stroll, and he smiled at her as she approached.

“Henry told me you might be stayin’ with us for a time. You’re a physician, I hear?”

“Yes.”

“And you fixed up young Nicholson?”

“He’ll be alright in a few days, but he should keep off his feet until the wound heals.”

Langston nodded. “You say so. Well, as soon as we can we’ll be headin’ to London, so I expect you’ll be needin’ a room. You might have to share a room with young Hank there, if that’s not a problem for you?”

“No sir, that will be fine.”

“Good, good, and now, if you don’t mind I have a few things to attend. Perhaps I’ll see you later?”

She smiled. “May I stay up here a while? Just to watch?”

“Of course, of course. Back there by the stern rail will be a place for you. No one will disturb you there.”

“Thank you, Captain Langston.”

“You there, Killick! Get that yard arm back up under my topgallant, and sometime today, if it pleases you?”

She walked aft and looked up, saw Hank up in the rigging with the rest of the crew. He was flying between the rope rigging and the wooden things up there, helping where he could or moving off to help someplace else if he couldn’t. For a 12 year old he seemed confident – and strong. Stronger than he had been the last time she’d seen him. How long had he been here, she wondered. And…why had he come…?

+++++

He came into the little cabin they shared long after the sun had set, long after the squall had passed, and Hank looked tired. Beyond tired. Exhausted. And he was filthy, too. Like almost everyone else onboard. There were no bathing facilities and the restrooms were ludicrous, nothing more than little benches perched out over the sea with holes cut into them so you could sit and get your business done. There was a bucket with white fleecy stuff in it next to the bench, excess cannon wadding that sailors used to wipe their bum. The sailors called it boom-wad, assumably because the stuff was used to pack down cannon balls before firing, but maybe because the stuff was used after a particularly loud bowel movement. Given the quality of food onboard, Judy thought, that was not as unlikely as she’d first thought.

And the water!

The water supply was kept in barrels and no one drank it, and with good reason. It tasted oaky, musty, and about five minutes after drinking a cup she had started cramping – then experienced one of those moments when you just know you’re going to shit your pants if you don’t get to a toilet – right now!

So she sat there on the bench shitting her guts out, accompanied by knowing glances and a few off color comments from the men sitting beside her.

Like her farts weren’t ladylike enough? Really?

There wasn’t a ship’s surgeon onboard Pegasus; most surgeons were employed by the Royal Navy and only the biggest merchantmen, the ships carrying cargo down the African coast or heading further east to India and Hong Kong had the resources to employ a physician. So Pegasus had a surgeon’s mate, a barely qualified young man with almost no schooling, but a modest willingness to learn.

So, she spent hours teaching James MacDonald the ins-and-outs of wound management, ways to prevent the spread of disease by exercising basic hygiene, then how to diagnose a few basic maladies, notably appendicitis – as a case popped up the next morning – when one of the sailors reported excruciating pain in his lower belly. He was cramping, farting up a storm, and hot to the touch; when she palpated the sailor’s lower right quadrant he screamed.

“Let’s divide the belly up into four quadrants,” she said to MacDonald as the sick sailor watched in dumbfounded agony. “Upper left, upper right, lower left and then lower right. When you’ve got extreme pain in the lower right quadrant there are two things you need to check right away. One is to palpate the abdomen…right here…and if you don’t get a reaction you move on to something called Murphy’s Rebound. We’ll talk about gall bladders later, because our patient has all the symptoms of a hot appendix.”

“What’s that?”

“A small vestigial sack on the bowel, and when it gets infected it has to come out. If it doesn’t it will rupture and the contents of the colon will spill out into the gut and a massive infection occurs. That can only be repaired by extensive surgery and a long course of…treatment.”

“So if we don’t get that thing out, you’re sayin’ ole Tom’ll die?”

It hit Judy then. The enormity of the challenge she’d just posed to herself, and the reality posed by these limited facilities. Let alone the little, and uncomfortably relevant fact that she hadn’t removed an appendix in over 15 years. And it wasn’t like she had a textbook to review.

Captain Langston soon heard about the medical emergency playing out belowdecks, and he came forward and found Judy and her patient on the forward gun deck. He listened patiently while she explained the problem and what she proposed doing, and he nodded. “What can I do to help?”

“I need a steady platform to work on. Is there any way you can make the ship sail more smoothly?”

“Aye. Dead downwind would do it, but right now that would head us to the Hollands. How long do you propose to spend on this endeavor?”

“It should take an hour, maybe less?”

“Okay, tell me when and we’ll bring her around.”

“Great. And could you get some men to help me get him to your cabin? I’ll need to use the same table I used when I fixed Nicholson’s ankle.”

“Aye, Mr. Henderson! Lay that on for the doctor, will you now?”

“Aye, Captain!”

She was waiting for this small entourage in the captain’s in-port cabin, and she already had a sheet over the table. She’d found a nail in one of the timbers overhead and hung a bottle of lactated ringers from it. She started an IV and flushed it – all while a dozen men looked over her shoulder. When she pulled out a digital thermometer and ran it over ole Tom’s forehead another dozen sailors appeared. Then Captain Langston walked in and the crowd parted.

The Captain watched as she injected morphine into the line, then watched, astonished, as she pulled out a stethoscope and listened to Tom’s breathing. She washed the old timer’s belly with saline and Betadine then put purple – purple! – gloves on, then slit open Tom’s belly and soon enough the Captain saw inside ole Tom and with that he turned and walked straight out to the deck and went to the rail and held on tight, breathing as fast as he could.

“Here there, Mr. Kildare! I said keep it smooth! The lady wants it smooth down there, so keep a good eye on them waves and try to keep to the troughs…!”

+++++

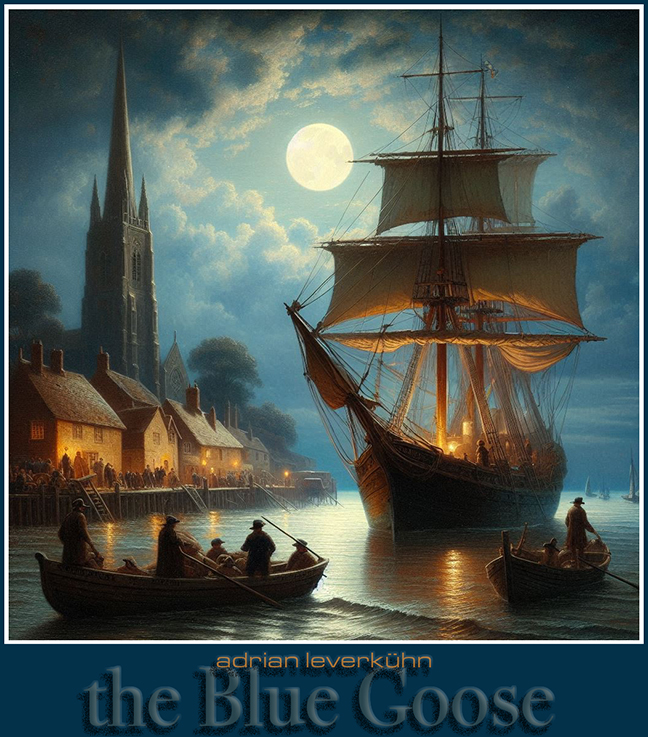

She’d been to London several times, of course, but not the London of 1821. The dome of St Paul’s cathedral was the biggest thing on the skyline, and as Pegasus had docked in Greenwich she had a decent view of the old part of the city across the Thames. Wharves and docks, for the most part, and dozens of ships berthed along the endless waterfront. Sailing ships but no steamships, yet some of these ships were huge, especially the warships. The crew were given shore leave and so, of course, word soon spread about the lady physician and the operation she had performed at sea.

The next day a delegation of physicians appeared at the gangplank asking to come aboard, and Captain Langston had the good sense to recognize a bunch of charlatans when he saw them so he told the lot of them to bugger off, and that he’d let no lady physician on his ship! Ever!

She took out her iPhone and opened it in airplane mode, then opened the camera and started taking panorama photos of the waterfront, then pictures of the crew at work as they loaded cargo for the last leg of their voyage back to Hull, the ship’s home port.

Two days later Pegasus was riding the outgoing tide down the Thames, then sailing out into estuary past Allhallows and Sheerness. She turned north, trying to fetch Yarmouth then made the turn northwest towards Grimsby and the Humber estuary.

Hank came up to her on their last day at sea, when Judy was standing on the aft deck lost in thought, watching the ship’s wake fade away into the sea. He came up beside her and hopped up until he was sitting on the rail, and with both hands on the rail and his legs crossed he leaned over and sighed.

“Are you going back tomorrow?” Hank asked.

“Are you?”

He nodded. “Yes. There are some things I want to do back home, then with the boat.”

“The boat?”

“Yeah. Bud gave me a 28 for Christmas. I’m going to get her ready, sail her over here this summer, as soon as school’s out.”

“By yourself?”

He nodded. “Maybe. There’s this guy who’d come if I asked him, but he’s never sailed before.”

“Sounds risky.”

“Yeah. Probably so. If it’s okay, I wanted to ask you about my mom.”

“Sure, go ahead.”

“What’s wrong with her?”

“Your mother had a difficult time when she was growing up. Her father was, well, he was kind of a monster, Hank. A predator. He tortured your mother, and he did so much and so often that your mom began to find places inside her mind where she could run and hide. Pretty soon she stayed in those hiding places all the time, at least until she graduated from high school. She was very smart so went to college to learn how to be a librarian, but she was still hiding whenever she could. She was still afraid of her father, afraid of the things he might do to her.”

“What things?”

“I can’t talk about those things, Hank. Not yet. I hate to say it, but you’re still to young.”

“Okay, I understand.”

“I know you do. You know, if I had a son I’d want him to be just like you. I bet your dad is real proud of you.”

Hank looked down, then shrugged. “Maybe, maybe not.”

“Does he ever talk to you? Alone, I mean. Just the two of you?”

“Not much. He’s busy a lot, and he goes away a couple of times every year. He’s gone a lot, really.”

“Oh, I didn’t know that. Where does he go?”

Hank sighed, then shook his head. “I’ve heard some stuff, but I’m not sure exactly, but he’s working on something that has to do with the sun.”

“The sun? You mean,” she said, pointing up to the star in the sky, “that sun?”

“Yup. I think he goes up there, too. To some kind of space station. I think it’s a secret space station where the Navy does things.”

Judy filtered these comments through her psychiatrists mindset, and she heard a boy with an active imagination building up his own father to almost mythic proportions. An astronaut, working on secret projects, and of course with no way to confirm or refute his adulatory feelings she had no way of knowing if this was the truth, or not the truth. What kind of delusion was he building, and why? Had it something to do with his mother? Was there something his father had done – to him?

“I thought he was a physicist?” she asked.

“He went to Annapolis but I think he was always interested in space.”

“I was,” Henry Langston said, coming up from behind.

“Oh, you’re back?” Judy sighed, startled and suddenly a little confused.

“I am. And Hank, you know you’re not supposed to talk about this stuff.”

“I know,” the boy said, his head hanging a little low.

“So, just what do you do when you’re away?” Judy asked, trying to take the heat off Hank.

“I’m working on a project that involves unusual sources of energy.”

“A secret project?”

He nodded.

“Do you go up there?” she asked, pointing skyward.

Henry sighed, then he smiled – slowly. “I do, yes.”

“So your son isn’t lying?”

“No. He’s not.”

“Are you lying?”

He smiled. “You are a shrink. I keep forgetting that.”

“Henry, are you lying?”

“I told you. It’s a secret.”

“That’s not fair,” she said, losing her cool. “But truthfully…just how long are you away?”

“Sometimes a few weeks, other times for months at a time.”

“Months? And you leave Liz alone to take care of the kids all the time you’re away?”

He nodded. “I know it isn’t optimal.”

“Optimal? Henry, that borders on neglect. Not just to your children, but to your wife.”

“It’s important work, Dr. Stone.”

“More important than your wife and family?”

Henry looked away; Hank looked up at his father.

“I used to think so,” Henry sighed. “Now…”

“Now…?” Judy repeated.

“Now there’s nothing more important to me than my family. There never was, not really. In my defense, after my first wife passed, well, I think I lost sight of that. I don’t know, maybe I was running away from all that.”

Judy looked up at him and nodded. “I can see that.”

“Now, may I ask you a question?” Henry said.

“Sure.”

“Is Elizabeth going to make it?”

“I’m not going to give up on her, Henry. Are you?”

“That’s not an answer.”

“No. No, it’s not, but the truth is I just don’t know, so I can’t give you a legitimate answer. Not yet, anyway.”

“But you’re not sure, are you? One way or another?”

“The only thing I’m sure of is that I’m not ready to give up.”

“Does that mean her team in Boston has given up?”

“I don’t know, Henry. They’re frustrated, but I don’t think they’re ready to call it quits, either.”

“We’re not talking about depression any longer, are we?”

“Henry, are you sure you want to talk about this around your son?”

“I don’t want to get in the habit of keeping things from him, Dr. Stone. He’s going to find out sooner or later, and sugar coating the reality of her situation with a bunch of lies isn’t going to feel real good when he finally learns the truth.”

“There are more appropriate ages for these kinds of discussions,” she admonished.

Henry turned to his son. “Do you want to listen to this, Hank?”

Hank nodded. “I think I understand that Mom is in real trouble, but I don’t understand why.”

“Do you want to understand that, Hank?” Judy asked.

“I probably don’t want to, Dr. Stone, but I think I need to.”

She nodded, really quite amazed by his stable sense of duty, even his maturity, but she turned and looked at Henry again. “There’s one thing I don’t understand. I’ve been here days, several days. When we go back, how much time will have passed?”

“In absolute terms, it’s as close to zero as I’ve been able to measure.”

“No time…at all?”

Henry nodded. “You have to think of this experience as happening entirely within your mind. No one here will remember you, but there are weird complications, unpredictable permutations. It’s possible, for instance, that the leg you treated will remain treated. It’s also equally possible that the boy may die, or lose his leg. The strength that Hank has gained over the months he’s spent here will, more than likely, disappear, but it may not. There don’t appear to be hard and fast rules, not that I’ve discovered, anyway.”

“Are you and your family the only ones who can do this?”

Henry shrugged. “As far as any of us knows, yes.”

“Is it possible that Elizabeth can?”

The possibility, apparently, had never occurred to Henry. “I don’t see how, unless she developed the ability on her own.”

“Or maybe she watched you?”

“Oh…”

“Well, I ask because whatever it is that’s affecting her is very hard to pinpoint. There are elements that fit what you might call a very profound depression, yet there are psychotic elements, as well. Or at least I thought they were psychotic elements, until…”

“Until you came here.”

“Yes. That’s right. Somehow, she’s making some kind of connection with your son, but I have absolutely no idea what it is, or now, even what it might be. This…” she said, sweeping her hands around Pegasus, “doesn’t fit any paradigm I know of. It doesn’t even begin to fit within any framework of reality that I’m aware of.”

“I understand,” Henry sighed.

“But I remembered what happened the first time I came,” Hank said. “It has to be real, right?”

“I think it is, too, Hank,” Henry sighed.

“I do too,” Judy added. “Shared delusions are certainly possible, but…under these circumstances? I think not…”

“It couldn’t be a dream, could it?” Hank asked.

Judy shook her head. “I guess it’s possible, but we’ll know for sure when we get back. And speaking of getting back? When should I return?”

“You can go any time you want, but I’d like Hank to stay for a few more days, until after Pegasus returns to Hull.”

“Why?” Judy asked. “Is something going to happen?”

Henry smiled. “Let me just say that Hank is going to learn something important.”

“How do you know that?” she asked.

“Because it happened to me, when I came on this voyage.”

Judy’s eyes registered astonishment. “You made this voyage? The same exact trip?”

Henry nodded. “So did Bud, my dad. We both did, when we were twelve.”

Judy swooned. “I feel kinda light headed, ya know?”

“You’ve been through a lot,” Henry said, reaching out to steady her.

“That’s the understatement of the year,” Hank muttered as he turned and walked off to the foredeck.

+++++

Pegasus ghosted up the Humber on a flooding tide, with just enough speed over her rudder to maintain steerage. Her sails, many still tattered after her encounter with the white squall, hung lifelessly; Captain Langston had deployed both her longboats with ten men in each to row pull her upriver, and, hopefully, to help her make Hull before slack water. If not, he’d have to anchor out and hope Pegasus did not end up on the flats, resting in the mud on her keel.

Judy went down into the crew’s space, a deck just under the forward gun deck and above the cargo hold, a space that had – perhaps – four feet of headroom. The crew slept in hammocks slung from the beams overhead, and the most senior men only had one man above them. The most recent hires hammocks were stacked three deep, and of course the hammocks swung in time to the ship’s motion.

And Judy had never smelled anything so revolting in all her life. Fifty men packed like sardines in a space only a little larger than the garage where she and Emily kept their cars, men who almost never bathed, producing a stench so overpowering she gagged as she entered the dank space. Her eyes began to water as she began duck-walking behind Hank, over to the hammock where Ian Nicholson lay recuperating, and as she unwrapped the gauze around his lower leg even by the light of her small penlight she could see that the wound she had sewn up was festering. The tear along his tibia was red around the margins and the boy was now febrile; it certainly didn’t help that the bucket of water he was drawing water from smelled of raw sewage. She took his temperature and shook her head, then drew another syringe of antibiotic and jabbed the boy in the flanks. She turned to Hank and nodded, then she followed him out to the passageway that led aft to the main stairwell. Once back up the fresh air she gasped – as if she had been holding her breath the entire time she’d been below – then she walked hurriedly to the rail and sucked in the warm, salt-laden breezes.

“That wound looks nasty,” Hank said.

“We need to get him up here out of that hell-hole, and someone needs to get him cleaned up.”

“You mean…like a bath?”

“Exactly like a bath. Don’t these men ever bathe?”

“Not that I’ve seen,” Hank sighed, grinning. “I hardly notice the smell anymore.”

“I know, but take my word for it. It smells like an open latrine down there.”

“Yeah, well, they shit and piss in buckets, and if the sea is rough the buckets spill when they fill up.”

“It’s a wonder they aren’t sick all the time.”

Hank nodded. “Maybe they aren’t sick because they’ve grown up around this stuff?”

She nodded to. “You’re probably right. Anyway, the least we can do is get his legs washed down and new bandages over that wound. Will he stay onboard when Pegasus reaches Hull?”

“I think his mother works in some kind of castle or something. Maybe she’s a cook and he stays with her when he’s not out to sea.”

“Well, I doubt he’ll be going anywhere if that leg doesn’t heal, except perhaps six feet underground.”

Hank nodded. “I’ll tell the Captain,” he said, turning and walking up the steps to the poop deck.

‘Why did his father want him to spend so much time here?’ she asked herself again. Henry had as much as told her that he had once joined this crew, on this very voyage, when he was 12 years old. And that Bud had too. Why? Was it some kind of a rite of passage? And that kid? Nicholson? Had he been injured like this over and over again? Would he die? Without her intervention she was sure that he would, so what now? What would happen if he did in fact survive?

She felt more that saw Captain Langston as he walked up beside her, and she looked at him quickly, barely acknowledging his presence as he stopped and put his hands out on the rail.

“So, you think the boy will pass on?”

“Without better care, yes. No one with his injuries can survive in that amount of filth.”

“Filth?”

“Yes. Squalor. Disease spreads easily under those conditions?”

“Eh? How so?”

Judy proceeded to explain the concepts of microbes and the spread of disease in confined quarters, but then she remembered that it was unlikely the man would remember any of these things once she was gone…so…in the end what was the point? The reality of the situation was that Ian Nicholson had been injured two hundred years before, and her presence here was almost like an overlapping layer of consciousness that might, or might not, have an impact on what happened next. But what of Hank? Hank was here to learn something, but what? And yet…Bud and Henry had wanted me to come here in order to learn something…but again, what?

The only answer that came to mind was Elizabeth.

One way or another Elizabeth had to have something to do with this experience.

“So, ye think I should send young Ian home, to this mother? Or should I keep him here?”

“He needs sunlight, clean water, clean bed linens, clean bandages, and his wound needs to be cleaned several times a day, and with clean water, until no pus runs from the wound.”

“The bone is sound?”

“Yes. If the wound heals he’ll be just fine.”

“What are those things ye poke in his arse…?”

“Medicine. Medicine that will help him heal.”

“Such things…these are from your time?”

She nodded. “That’s right.”

“I am not comfortable with such things taking place. Henry didn’t tell me you would be doing this. Are you a healer, where you are from?”

“I am. Henry’s wife is ill, and I’ve been trying to help her.”

“Ah, well then, perhaps he has a reason for all this.”

“Yes, perhaps so…but I am not aware of any.”

“You’ll be goin’ home soon, I take it?”

“I think so, yes.”

“A pity. I was growing fond of your company.”

She smiled. He had invited her to eat with the officers every night and Henry had turned out to be a real gentleman. “I’ve enjoyed my time here immensely,” she said, smiling.

“So, stay.”

“What?”

“Stay with us, here. We’ll be going to France soon, and then on to Lisbon and Marseilles. Fewer storms this time of year, too,” he said with a grin.

“Is Hank staying?”

“Ah…alas, no. There’ll be no need for that now. The boy has reset his course, and he’ll be doin’ fine now.” He paused a moment and she thought he looked as if he was summoning his courage before speaking again. “You know – if the idea be pleasin’ to ya – well then, ya might stay and take care of young Ian, if ya be alookin’ for a reason ta stay, that is.”

She looked at him and realized what he was really asking of her. What he really wanted to say; that he wanted her to stay. Or, he…wanted her. And he was as tongue-tied as any fourteen year old she’d ever encountered, too.

“You’ll be going to France?” she asked. “Really?”

“Indeed so. Well, you give it some thinkin’ and you’ll let me know. Anyway, we’d love to have ya.”

He walked off, as suddenly calling out orders and…in all likelihood just blowing off all the anxiety he must have felt before he walked over to ask her that one question. Because, obviously, it had to have been on his mind. And she’d been stunned by his question, too. As stunned as she was amused. ‘But,’ she said to herself after a few moments passed, ‘why not? Why not stay here a little longer? There’s no cost to me because whenever I decide to go home, well, what did Henry say? Exactly no time will have elapsed. So, I could stay here a lifetime, or even several lifetimes, and not age even a day! But…think of the things I could learn…?’

+++++

Pegasus got her lines ashore late that afternoon, only making it to the wharves off High Street with the help of a freshening breeze. Almost immediately Henry Langston strode down the gangplank and walked across to the counting house, then to the bankers, and when he came back to his ship he looked relieved. Judy knew right then that the financial strain on him during the voyage must have been staggering, but she was the first to admit she didn’t understand nineteenth century mercantile finances.

Yet Henry also had made arrangements for clean well water to be delivered to the ship, then he had the crew set about scrubbing the ship, literally from stem to stern. He planned to move Ian Nicholson to a new room he wanted built, right off a new cabin for a ship’s surgeon. Henry had listened, and paid close attention when Judy taught him about diseases and how they spread in confined spaces, and his problem-solving mindset had immediately set about looking for solutions.

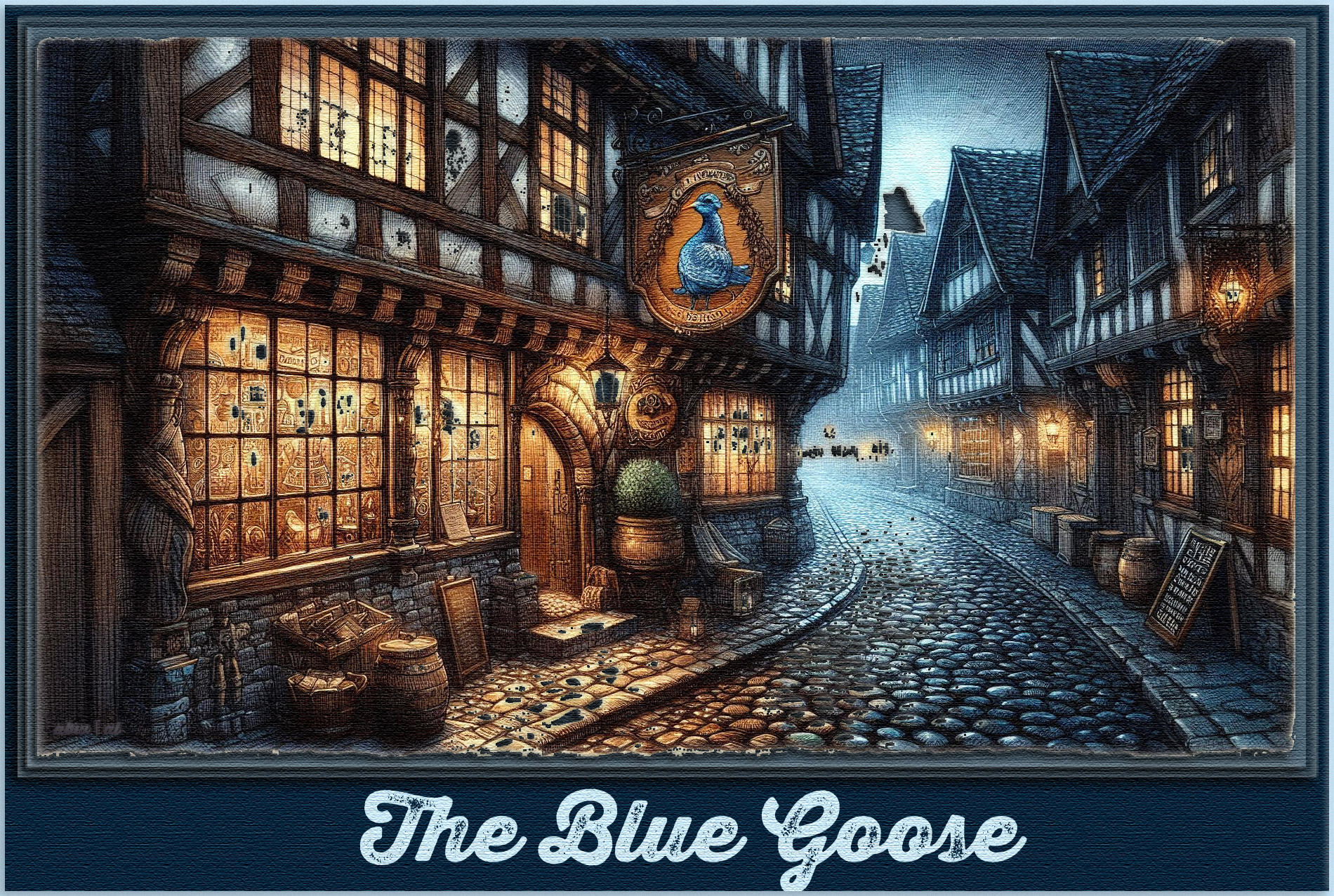

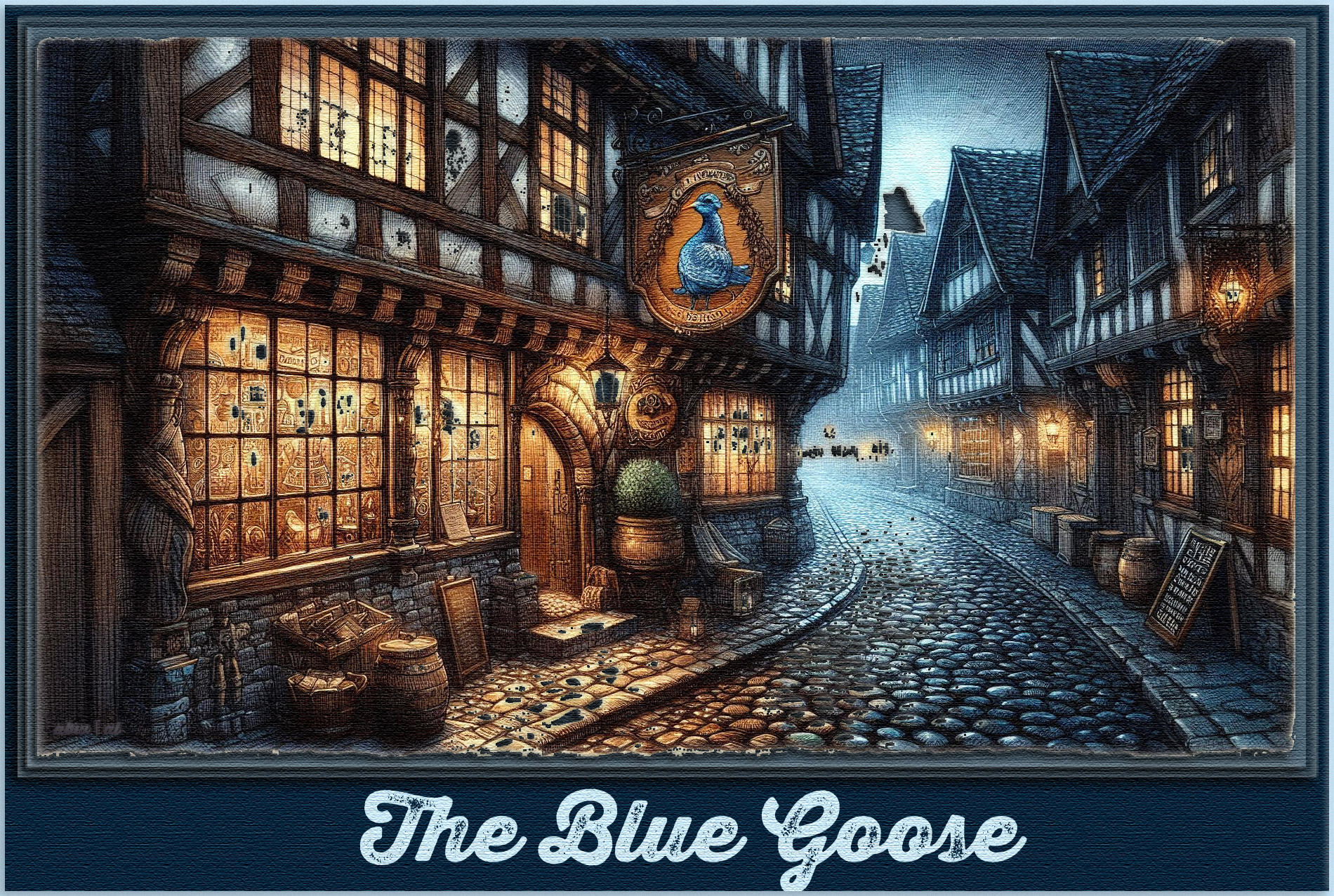

After the sun set on the day, Henry asked Judy and Hank if they’d care to join him in the city for dinner, and so an hour later the three walked down the gangplank and up High Street to Henry’s favorite pub. They kept a room for him there, up in the living spaces, and he spent nights there when Pegasus was laid up in town. “The pub, by the way, belongs to me brother. Ben’s his name, in case the matter comes up…”

“Ben?” Hank asked.

“Yes, lad. Ben’s his name, and can you imagine that now…”

As they approached the pub, Hank thought the establishment looked more like a house than the others he’d seen along the street, and the building was even set back from the street a bit more than the others. There were rose bushes out front, and a carved wooden sign hanging over the door; oil lamps were already aglow inside the pub, casting amber light across the roses and out onto the cobblestone streets, and Hank could smell roasting beef and potatoes on the air.

As they walked up the bricked walkway, Hank looked up and tried to read the name of the pub carved into the sign, but he had to step aside a bit to see it…

But he could not believe what he saw.

For the name of the pub was The Blue Goose, and there was even a goose carved on the sign. A goose as blue as the sea, as blue as…Gertrude was.

They stepped inside the pub and faces turned their way, and conversations stopped.

Hank walked in and almost immediately his eyes were drawn to a man behind the counter filling steins with a deep amber brew, and without a moment’s hesitation he knew the man’s name was Ben. Because he looked just like his brother – indeed, all grown up now but just like his very own brother.

But the strangest sight of all was the deep blue goose sitting on Ben’s shoulder.

For the goose was looking right at Hank. And the goose was smiling now, too.

© 2025 adrian leverkühn | abw | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | and this is a work of fiction, plain and simple.

So, once again, we be a wishin’ ya a Very Merry Christmas, and we’ll be pleased to find you in our home waters next time out. Adios.