Pardon my absence from the online world, but I have been writing, almost to the exclusion of everything else, but enough of that. I first worked on this story in 2007, posted the three parts over a couple of years yet never really completed the third part. I started there this time and reworked the last part first, then rewrote the first two sections, then the coda. This little story is about 300 pages (over 100k words) and takes a few hours to get through, so you’ll either want to take it slow and brew a bunch of strong coffee.

Music? Why don’t you start with The Rain Song, by Led Zeppelin, then dig out an old Moody Blues tune called What Are We Doing Here.

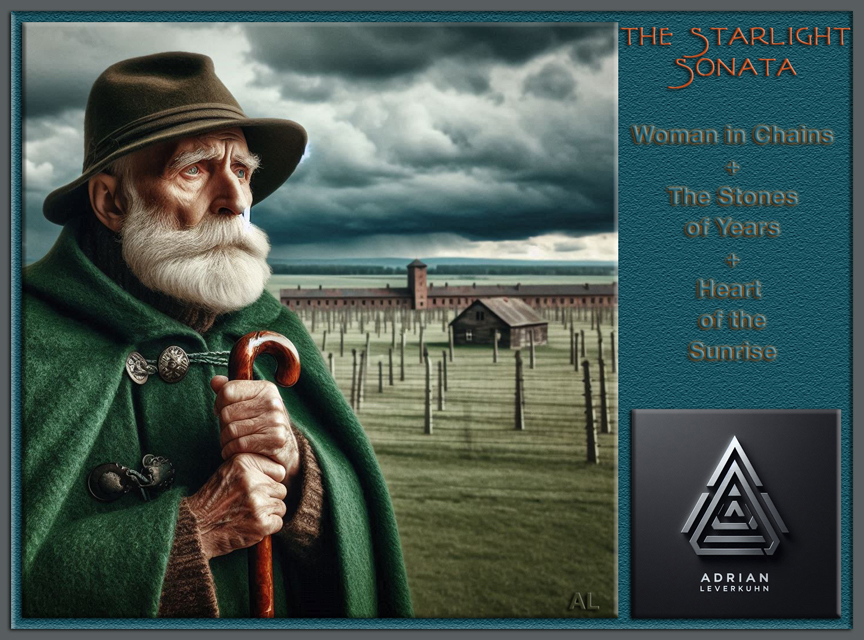

THE STARLIGHT SONATA

Part I: Woman in Chains

Tracy Tomlinson walked down the stairs as quietly as she could. She slipped into the kitchen like a shadow and put on coffee, then walked outside and down the driveway; she groped around in the dark for the newspaper, nearly tripped over a football when she bent over to pick it. It was still too dark out to see the headlines, but she hardly cared about them anymore. Mark kept up with all that stuff. The world would get along just fine without her knowing who had been fighting in what war over this or that reason last night, and she knew she’d greet tomorrow’s wars with about as much interest.

Yet she could remember a time when she’d cared about the world – and she knew she had. Like she had once cared about how she looked, about what she ate, or even what Mark thought of the way she looked. There’d been times when she worried what her friends thought of her, even what her children thought of her – but not any more. She had grown tired – tired of life, tired of living, tired of eating and tired of even breathing. Fucking Mark, she remembered bitterly, had been the last to go. She’d always loved a good rough fuck, but Mark had lost interest after she put on a hundred pounds, so now not even that simple pleasure remained. She was numb now, and it was like all those things resided somewhere in the back stacks, lost somewhere on a forgotten list with all her other useless memories.

She climbed the steps back into the kitchen and pulled down two little packets of flavored oatmeal and put water in the microwave to boil, then walked upstairs to her boy’s room. Brian was on his back, his morgen-bone rising under the sheet from the center of his bed; the first time she’d seen that she had almost laughed – because the spectacle looked like the troops were raising the flag on Iwo Jima once again. She shook her head at the memory and turned on his light, called out his name, then walked down to Stacy’s room – but heard the shower going in the hall bathroom and knew her daughter was already up. When she poked her head in their bedroom she heard Mark in their bathroom, his electric razor grinding away through day old stubble. Already the room smelled like his Old Spice deodorant and the scent brought back another bundle of useless, if unwelcome, memories – like the last time she’d touched herself down there and everything had felt cold and dead – or was lifeless the correct word, she wondered.

‘Like this waste of time I call my life,’ she told herself as she returned to the kitchen.

Once there she pulled out the big skillet and put it on the range, took eggs from the refrigerator and sausage patties from the freezer and set out everything she needed to cook her family’s breakfast, and then she poured coffee for Mark and Stacy. Brian was still, she thought with the last vestiges of a smile, a little too young for caffeine. Too young to do much this early in the morning besides hump his pillow or brag about how well he was doing at football practice.

She scrambled two eggs for Stacy and three over-medium for Mark, poured water over Brian’s instant oatmeal, then set out a platter of sausage patties on the table and poured orange juice for the three of them. As they flooded into the kitchen she walked by them silently and walked back up the stairs to her bedroom. She locked the door and sat down on the edge of her bed; she felt like crying for a few minutes, then walked into the bathroom. She looked at the bottles of Prozac and Xanax in the medicine cabinet and wondered if these were all she had to look forward to now, like would there ever be anything more than chemically induced oblivion to look forward to? Pills and a nap, again and again, then wake up and start it all over again, wearing a beaten path in the house’s old brown carpet on her way to an early grave.

She took her prescribed dose and lay down on the bed, listened as the kids got into the car with Mark and headed off to school. She hoped sleep would come soon for her, and take her far, far away.

+++++

She knew she was far, far away because the ringing in her ears was so out of place.

Nothing here seemed right.

She was on a beach, she was sitting on a sandy beach; she knew she was sitting because she could feel wet sand under her legs and feet. The sun was hot; a soft breeze was blowing, lifting her hair and filling the air with smells of a salt-laden sea. Mark was standing beside her, his back turned toward her, and he was holding a huge mass of heavy chain. She looked down and saw twisted and rusted links wrapped tightly around her thighs, forcing them tightly together.

Why… Mark, why? Why have you done this to me?

The ringing was insistent now and she turned, looked over her shoulder at rows of palm trees swaying in the wind. She wanted to walk into the trees, look for the ringing lost in the darkness because the sound seemed to be coming from inside the forest. Suddenly she turned back to the sea, remembered something. A sailboat sat offshore a few hundred yards away. A man was on deck, looking at her from time to time, and she saw a gray dorsal fin circling the boat. She could see the man quite clearly, yet his face was invisible, like he was not quite a part of this dream. The man was playing a grand piano on the boat’s foredeck, and she looked harder at him now – because something was wrong with the dream today. She could just see strings attached to his arms and hands; some strings were stretched tautly, others dangled loosely, and all vanished in low, gray clouds that had just swept just overhead. She could see that the man’s movements were being controlled by these strings, and she gasped when she saw the man’s helplessness.

The ringing grew louder still. Then she heard someone knocking at the door.

The door? On a beach?

She opened her eyes; she saw her bathroom door was open and felt herself adrift in the hazy, shaded ambivalence of her meds. She looked at the old clock on the table by her side just as the knocking started again. It was nine thirty. Daylight, she saw. She swung her feet to the brown carpet and stood uncertainly, fell back to the bed with practiced ease and let her head spin slowly, let the pressure in her chest subside, then she stood once again and walked down the stairs.

She could see two police officers on the front porch; one was looking in the window by the door and he saw her, stood back and waited. She reached for the door, still not sure if she was awake yet, or if this was a new, very different part of her dream.

She opened the door, then squinted into the harsh light of day.

“Mrs Tomlinson?” One of the officers said.

“Yes. Is something wrong?”

“Ma’am, could we come inside,” the other officer said.

She was waking up now; she could feel something dark circling overhead. Something wrong. She could feel it all around her now. Something was terribly wrong with this place.

She opened the door and let the men in and closed it behind them. She had the impression neighbors were standing across the street looking at her, and for some reason this scared her. She led the officers into the living room, asked if they wanted coffee and what this was all about.

“Ma’am, there’s been an accident. Is there someone we could call to be here with you?”

“An accident?” Tracy Tomlinson said, her eyes going wide as the pressure in her chest returned, and she was now fully awake. “What? Who?”

“Perhaps you’d like to sit down, Ma’am…”

“No, I want to know what’s wrong,” Her voice bit into the rising tide of fear welling up deep inside, while hysteria rippled through the air around the empty house. “Why are you here?” she asked the closest officer. “Why? Tell me why?”

“Ma’am, does your husband drive a white 2023 Volvo SUV?”

“Yes! What? What…are you saying?”

“Ma’am, that car was struck by a train this morning at the grade crossing on Paterson Parkway. There were three bodies in the car, but, well, there was a fire, and I hate to inform you that…”

“What? Where are my children?”

“Ma’am, we’ve identified the bodies in the Volvo, and, uh, I’m afraid they’re, uh, well, they are your children, well, they’re gone, Ma’am…”

She was aware of time slowing, of the room spinning, then growing dark, darker, darker with each slowing heartbeat – the pressure in her chest suddenly crushing the life out of her, then just as suddenly everything grew quiet, and the purest white she had ever known filled her sight. She was surrounded by clouds speeding by and suddenly felt like she was flying, flying into this light, and yet everything was cold in this new dream, and suddenly everything was so very quiet.

Then she felt like she was flying at great speed – but straight down. The sensation of speed was vertiginous, the nausea overwhelming, and then pain the pressure in her chest returned.

‘Why does my chest hurt so much?’ she said to herself. ‘What a strange dream this is.’

+++++

She opened her eyes, and still all she saw was fog.

But there were people in the fog now, and they were all around her, their eyes full of concern. There was a bright light overhead, a sharp pain in her left arm, disjointed faces in funny paper hats with masks over their mouthes and noses. A bald man with kind eyes behind small round glasses was leaning close, looking into her eyes – and she wanted to fall inside his kindness.

“It’s alright Tracy. You’re going to feel a little sleepy now. Don’t fight it, okay? You’ll feel better when you wake up.”

Falling again, further this time. Darker now, darker than before, but she felt warmth all around her, the welcoming warmth flooding through her like a wave.

‘How much longer is this going to last?’ she said to the reflection of herself down below. As she fell, lost inside all these sudden unfamiliar motions, she became aware of a sound very much like the clatter of heavy chains being hauled across the floor of her dream…then she saw the man on the sailboat, and the brown eye of a whale staring at her. Why did she feel like the whale understood what was happening to her?

+++++

She knew she’d been asleep for a long time, yet she knew she was still in her dream. Mark was here beside her. She felt him, and him alone for a while, and she knew he was near because she heard the chains that had shackled her to him for so long. The chains made a horrible music, a forlorn note much like a single oboe – and the monotonous music pierced the fog around her; the melody was painful, discordant, and she longed to find the oboist and correct him. She’d never held an oboe before, let alone played one, but an oboe was hovering in the air before her eyes and suddenly she realized she knew how to play it. She saw chains materializing in the air all around her, hundreds of them, and each one was carried by Mark. Only there were hundreds of Marks now, all looking at her with pale, lifeless eyes, all holding their chains up for her to see, before pitilessly walking away from her.

The chains seemed to rattle but she heard their music, too. Music everywhere, all around her, yet it was the music of her chains. She looked at a link in one of the chains and saw that it was a horn of some sort. She didn’t even know the name of the instrument, yet when she looked at another link and another and another – one by one all the links within all these chains turned into a vast ocean of musical instruments. They advanced on her and held her firmly in the dream just as surely as Mark’s chains had. She was suffocating again, trying to pull free but her hands were weighted down by chains that writhed about like coiling snakes, then as suddenly changed before her eyes into clarinets and piccolos and violins. And yet in this dream she blinked and tried to turn away, but everywhere she turned it was always the same. Chains rose, coiled in the air, readied to strike at her and as suddenly shimmered and mutated before her eyes. Before long she was surrounded by hundreds of instruments, each one being played by reflections of herself, and as suddenly the sky filled with stars. millions and millions of hot, white stars.

+++++

Todd Wakeman flipped through the chart and looked over the patient’s entries for the last 24 hours. Nothing made sense. Chemistries were all in range, surgery to repair the small clot in the base of the woman’s brain had gone off without a hitch, yet for some reason the woman had never regained consciousness. She had been in a coma for two months now, yet on more than one occasion nurses had heard the woman singing. Well, not exactly singing, at least not at first. The first nurse to observe this phenomenon had, in the middle of the night, heard what she thought was a co-worker’s innocuous humming, and this she did not report. Later that morning an orderly heard what sounded like simple singing, as in notes from a classical piece; when the woman in the coma launched off into an impromptu solo session, the orderly screamed and staff neurologists were duly summoned. One of the physicians, a classically trained pianist, noted that the woman’s vocalizations were totally original compositions and that they resembled something akin to Gregorian chant; nurses began to hear a pattern in these episodic outbursts and noted the time and duration of each. These outbursts happened almost every morning around eight, and lasted anywhere from a few minutes to a half hour.

Todd Wakeman was in the fourth year of his neurology residency, and he’d neither seen nor heard of anything like this happening before. The patient was presenting ‘Something New,’ and usually when anything in the ‘Something New’ category happened, it tended to be a ‘Very Big Deal.’ So the attending professors had looked her case over, ordered more tests and scans, but when nothing new showed up in their tests they soon lost interest in her case – again. Though Wakeman had no idea what was going on, his way of looking at medicine was grounded in curiosity; he soon noted that these singing episodes seemed to presage an electrical swarm, in as much as her EEG recordings went from almost brain-dead to near total brainstorm in the seconds just before her vocalizations began, and they as quickly subsided when she grew still again.

Wakeman had a new group of medical students that had recently begun their clinical neurology rotation and he was going to present her case that morning, perhaps to see if he could get some original ideas out of them – because it couldn’t hurt. He looked at his watch: 7:30. They would be here soon, and if the timing of the woman’s recent swarms was a solid indicator, the group would be in for quite a shock.

He closed her chart and walked out to the nurse’s station, a peculiarly impish little twinkle taking flight across his empath’s face.

+++++

“Next patient is a Mrs Tomlinson. Tracy, I think. Forty nine year old female suffered a moderate CVA after being told her husband and children were killed in an MVA. Surgery to correct two months ago was non-eventful, but she has never regained consciousness. Mother and a sister visit about once a week now, but no response from the patient. Vitals are good…”

Wakeman rattled off the recorded stats and other recent observations…all but the noted episodes of musical activity. And as luck would have it, he was just about to go over how to assess a comatose patient’s neurological status when the swarm began on her EEG. And as the med students looked on, the singing began.

Gently at first, but insistently, she began to sing the prominent parts of a piece of music that seemed hauntingly familiar to Wakeman; it was just the second time he’d been around at the onset of one of these episodes, and he still found it shocking, literally quite unnerving. Now he turned to look at his students, then the woman.

Her eyes remained closed, her body motionless, but her mouth moved precisely, methodically, while the notes that came from inside her mind were as precise, and as methodical; they were, in fact, tonally pure and structurally correct. Wakeman looked at the shocked expressions on his students’ faces and grinned, if only because he understood completely what they were feeling.

One of the third years, a girl named Judith Somerfield, stepped forward with a penlight and opened an eyelid, waved the light in front of one pupil, then the other.

“Equal and non-reactive,” she said. “But, isn’t that impossible?”

The girl took a ball point pen and went the end of the bed; she pulled up the sheet and ran the cap of the pen up the bottom of Tomlinson’s foot.

There was no reaction. None at all.

“I don’t get it,” Judy said. “Is this a gag, maybe like some kind of a twisted joke?”

One of the other students, a teenaged boy with “MacIntyre” embroidered on his pristine lab coat, leaned forward, lifted the sheet covering her arms.

“The fingers,” Ben MacIntyre said quietly. “They’re moving. See! She’s playing notes.”

“What IS that song?” one of the other students asked.

Judy Somerfield looked annoyed, because any dolt really should’ve known this music. “Romeo and Juliet. Prokofiev. The Death of Juliet! Geesh!”

Wakeman smiled; like always, this latest batch of med students was still ultra-competitive, they were always standing by with a ready put-down, looking for one way to get ahead. At least some things never changed.

“Has anyone done EEGs when this happens?” Somerfield asked.

“Oh, yes, we managed to figure that one out for ourselves,” Todd quipped. “Nominal coma until a sudden swarm, then total overwhelming cascades.”

“Interictal discharges?”

“No.”

“Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy!” MacIntyre chimed in.

“MRI and PT are both clear. No spongy tissue observed,” Wakeman said, and the boy looked crestfallen.

“Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy?” Somerfield asked hesitantly.

“Good guess, but nothing in the surgical record supports that, and neither the paramedics or the cops reported doing CPR, because no breathing anomalies were noted.”

“Cardiac enzymes?” Judy asked.

Wakeman was brought up short by that one.

“Where are you going with this?” he asked. “An undiagnosed cardiac episode?”

“Possible, isn’t it? If everyone was focused on the CVA, maybe they overlooked an infarct. A small, transient…”

Wakeman rubbed his chin. “Possible. Where would you look?”

“Are the ER records up here?”

“No.”

“First I’d get those, see if anyone did gases and enzymes, see if anyone suspected cardiac involvement and ruled it out.”

“Okay, y’all stay put. I’ll go send for them.”

‘Could it be so simple?’ Wakeman said to himself. ‘These kids were just coming off a rotation in Cardiology, so of course that’s where their heads were at, but…could it really be so simple?’

It wasn’t.

+++++

MacIntyre and Somerfield stood outside Wakeman’s office two days later; they hesitated, second-guessed themselves, wondered aloud for the hundredth if they really should tell the head resident about the idea they’d had. Judy had been the first to figure out the key element, and she had talked to Ben MacIntyre after rounds the next morning.

“Didn’t you notice? She gets about half way through the piece then stops, retraces her steps and tries again. She gets to that same chord sequence and tries a few times to work through it, then falls back into unresponsive coma.”

“It’s a difficult passage,” Ben said knowingly.

“You know it?”

“Of course! What kind of moron do you think I am?!”

“A young moron, Bennie. I still can’t get used to an fifteen-year-old third year medical student…”

“Screw you,” MacIntyre said defensively.

“Look, I…”

The door opened; Wakeman stood there sleepily, rubbing his eyes. “You two gonna duke it out, or what?” he growled.

Somerfield and MacIntyre jumped back, startled.

“Well?”

Judy tried to look more assertive than she felt and just threw her idea out there. “It’s about Tomlinson; we’ve been thinking…”

“Now there’s a startling concept,” Wakeman deadpanned. MacIntyre frowned.

“… thinking that, well, she gets through the piece, the Prokofiev, but she gets stuck about a quarter of the way through. Like an old vinyl record. Stuck in a groove, almost. She keeps bouncing back to the beginning, starting over and getting to the same point. She did it three times this morning, then fell back into coma…”

“It’s the same music? The same…”

“Yes. Prokofiev. The Death of Juliet. From the ballet. That ending is regarded as one of the most evocative, emotionally pure pieces in the classical repertoire. And I can’t help but wonder why? Why that piece, and why is she getting stuck there?”

“So, we were…thinking, what if we kind of jump started her – when she reached that part of the phrase?” MacIntyre interrupted. “Judy and I were thinking – what if we played along with her? You know, from the beginning. And then, when she gets to that part…”

“What? You talking a CD, or what?” Wakeman asked incredulously; he could see where this was going and was startled by the ease and clarity of their proposed intervention.

“No sir,” Somerfield resumed. “I’ll play the cello or viola; Ben the violin. We’d be set up, ready to go in the early morning, waiting…”

Wakeman was startled by the possibility. If they could get Tomlinson past this stumbling point, what would happen? He riffed through the possibilities, wanted to ask a couple of the department heads, see about getting a video camera set up, maybe call her family to come in. These were fascinating possibilities, he said to himself, even if uncertainty reigned supreme.

+++++

The dream began again and she withdrew from it, wanted to run from it, wanted to get back to her other music. She resented the interruption, resented anything that took her from her music now. She worked constantly; instruments she had never known had become her dearest friends, and she composed new pieces all the time in her other dreams. But this one piece kept coming back to her, and always it was the same. She always lost her way when…

…when she arrived at the beach, the water and sand against her legs and feet, the still unknowable cadence of Mark’s chains…all the elements of the dream were the same. Then it came to her as on an errant breeze: she was chained to this music just as surely as she had been chained to Mark. The wind, the trees swaying, the man on the huge sailboat playing the piano…the man…the man… the man in the stars…millions of stars, everywhere…

Why did he always get stuck at the same place in the music? Or was it the puppeteer? Did the puppeteer not know the music? But why? Why would the puppeteer not know, why would he lead us here, only to then lose his way?

But something was different about the dream today. Something about the sound was different. The piano was…no…what was that? New instruments? The puppet-man turned and looked at her; his smile was changing, and she could see he was wearing some kind of ragged prison uniform. There was something different about the instruments this time, too. Was it their time signature? But…why?

She could see the puppet’s face now! His eyes were clear and full of empathy, his smile full of gentle mirth, yet she could see that he was proud, too. She gasped as the puppet-man nodded his head, turned away, turned back to the piano, and his hands danced over the keyboard smoothly now in an uninterrupted run.

Tracy Tomlinson opened her eyes and looked skyward; she cried out – and was blinded by the light of six million suns…

+++++

Wakeman looked at her EEG readings as Somerfield and MacIntyre played through the music on their bowed instruments; he couldn’t help being swept away by the simple rendition of this music, even by the noble majesty of the moment. He looked at Tomlinson’s mother and twin sister as they stood beside the hospital bed, their whole being radiating both the hope and the despair they had felt since the accident.

He checked the leads feeding the EEG, watched Tomlinson’s brain waves trace wild lines across the screen. He picked up the stream of graph paper that slipped out the side of the machine, looked at the gathering swarm of neurological activity. Whatever it was, whatever was happening, he saw it was huge, overwhelmingly so. Indeed, he had never seen anything like this before, not in any patients or research subjects.

And he could tell the decisive moment was fast approaching without even looking at Tomlinson.

“She’s in REM sleep now.” He said quietly as he looked up from the tracings. “Look at her eyes!”

Tomlinson’s eyes were still closed but they were moving around rapidly under the eyelids. This had not happened before and Wakeman’s sense of expectation grew even more.

Her hands began to move now; slowly at first, but more rapidly as the decisive moment approached.

Somerfield concentrated on the music, yet she was torn between two contradictory impulses. She wanted to watch Tomlinson, watch her reaction to the music, but she wanted to be as technically perfect as she had once been. Yet with just the two of them playing, she knew this would never do this music justice.

MacIntyre felt the tension in the room increasing with each note he played, the anticipation building ever higher as the music neared the anticipated breakdown, the inflection point of Juliet’s death. Would the patient, could she make the transition? He held his old violin tightly with his chin; the bow in his right hand danced across the strings as if possessed, leaving little puffs of rosin on the down-strokes. Of course, he was beginning to sweat…

Tomlinson’s voice was crystal clear now, and keeping perfect time to the music – but as the moment approached it wavered, then broke, and Wakeman hovered on the edge of howling frustration, felt like screaming as helplessness tore through him.

And then the moment was upon them.

Somerfield and MacIntyre played steadily through the passage.

Tomlinson’s voice held, broke again – and then held.

Wakeman looked at the EEG; all activity was off the scales, like the woman was in total sensory processing disorder. It was impossible that anyone could remain focused on anything, he thought, let alone sing or carry a tune. He turned away from the machine, looked down at her…

“Her eyes!” he said in an excited whisper. “They’re opening!”

Somerfield hesitated, looked away from the music.

“No, no! Keep playing!” MacIntyre pleaded, and Somerfield returned to the music without missing a note.

“Nurse, put some saline on a four by four, wipe her eyes please,” Wakeman said, and one of the duty nurses bent gently to the task, carefully wiped Tomlinson’s eyes.

The final, powerful descending notes – the long sigh of death, and then the lingering transubstantiation – crossing time and space on Juliet’s way to the infinite – the room was full of strings and one human voice united in the common language of song, and remained so until the final notes were played.

Wakeman looked at Tomlinson. Her eyes opened a bit more, the EEG was meaningless now – all readings nonsensical – and Wakeman was aware everyone in the room was willing her on. The people and the music had united as one…

They all rose as if on a wave and as suddenly broke and fell. Tomlinson’s lids just barely parted in that moment, and Wakeman gasped at the almost immeasurable power he saw in the woman’s eyes; then as suddenly Tomlinson’s eyelids closed and the EEG fell back into an almost total flatline.

“Well Goddamn it all to Hell!” he howled in his best West Texas draw – before he stomped out of the room in rabid frustration.

“She opened her eyes!” Agnes, Tracy’s mother cried. “Did you see that, Becky? My baby! My baby girl opened her eyes!”

Becky and Tracy had always been closer than close; too close, some said with a knowing smirk. There was, it had been commented upon more than once, an unnatural connection between the two of them. But now, as Becky looked into her sister’s eyes she felt a boundless, raging terror boiling inside her sister that left her feeling desolate and alone… and empathically terrified. As Tracy fell back into the impossible visions of warped stars that filled her mind, Becky’s body suddenly felt possessed by music – illimitable, endless music that gripped her heart in cold fury. But where the devil had it come from…?

+++++

Todd Wakeman was on the telephone in his office, his fingers drumming away loudly on the cheap formica desk; both Somerfield and MacIntyre could see he was agitated so they were quiet now. Todd was trying to talk with someone, anyone, at the Julliard School after listening to one of the clinical art therapists from the Neuro ward. This therapist had heard the music and watched from the corridor, and she too had been completely confused by what she’d seen, but had presented Wakeman with the kernel of an interesting idea.

He was finally connected to someone, a woman named Ina Balin, apparently with the school’s community relations department, and Wakeman got right to it; he laid out the basic outlines of the Tomlinson case, then what Somerfield and MacIntyre had done that morning, and Balin seemed impressed by the story, if not exactly interested.

Then Wakeman told Balin what the clinical art therapist had told him, and what she had in mind – and Balin had a good laugh at that.

“I’ve heard a lot of off the wall stuff before, Dr Wakeman, but I think this tops the list. When did you want to do this? Assuming we can pull it off, I mean.”

“As soon as we can, really. It feels like we had some kind of breakthrough this morning, and I don’t want to let that slip away.”

“Okay, I think I understand. Say, do you think the family would mind if a TV crew came along?”

“There could be some privacy concerns, you know, like HIPA stuff, but I’ll ask. Even so, I don’t see a big problem if it’s not for broadcast television and not in the hospital. We had a video camera in the room this morning, but that’s a long way from a news crew.”

“Okay, well let me get back to you. Oh, before I forget, where were you thinking you’d like to do this?”

Wakeman told her and she laughed again, then said she’d get back to him in an hour or so.

“Well,” Judy Somerfield asked as she leaned forward, “what did she think?”

“Nothing definite,” Todd sighed, “so I guess that means definitely maybe.”

“Cool,” Ben MacIntyre added. “Maybe is always better than ‘Hell no’ any day of the week…”

“Got that right,” Somerfield said.

“Any day of the week,” Wakeman mumbled. “Any day of the week.” He leaned back as ideas ran through his mind, weird, playful ideas…but then he asked himself the most obvious question. ‘Now, why does any day of the week suddenly seem so important?’

+++++

She drifted amongst fields of pulsating stars, and still they sang to her.

Notes as pure as a sigh, as discordant as death; the stars knew no end to the range of their music. She listened, and she learned, and still the music came to her on never ending streams of relentless starlight. In time she grew exhausted, yet still the music came.

It occurred to her more than once that she was in the presence of a vast, inscrutable teacher. At times she could feel an odd presence all around her, an infinite, vast presence in the darkness, waiting for her, and always watching her. She made mistakes and felt palpable fury building among the stars, and then she would find a new chord and the presence settled as a child might when her mother was putting her to sleep. But the steady music of these stars never let up; this teaching, this watching and measuring – the music came relentlessly and never stopped coming.

She could no longer remember a time when she hadn’t been blinded by this starlight, blinded by overwhelming bursts of music within the light, and at other times she had felt herself streaming through fields of stars at impossible speeds. At these times she had felt something new and different within the light itself, something or someone so familiar the sudden remembrance of brought great pain. Memory pushed inward, tried to push away the music; then she was aware that this ‘something’ had been a part of what she once had been. As this dawning realization flooded into consciousness, the speeding light tore at everything important to her, rendered her memory useless. Sudden pain reached inside the womb of light – the pain reached in for her, pulled at her, twisted her into impossible new shapes, and yet, in a heartbeat the music stopped – and the stars as suddenly grew silent – just as a vast, infinite darkness settled all around her.

For the first time she could remember in this new life she felt the terror of aloneness. She fell into this well of darkness and tumbled mercilessly for what seemed an eternity, but at last a single star appeared. And this single star shone in the darkness, the star’s single note piercing the infinite loneliness that had surrounded her. She focused on the star, focused on the purity of the note and responded with one of her own; soon another star appeared, and another, and then she was composing again, dancing through joyous fields of stars, running free among fields of stars as a child might when running through fields of bright summer flowers.

And yet she knew the time was coming again. The puppet’s odd music was coming again, and the stopping would return, and she knew there was nothing she could about all that now.

She always felt it first as a remembrance, yet too as an unexpected pain, then an unbroken stream of notes among the blazing light as new stars joined the stream, but eventually remembrance returned as a single, forlorn note falling away into darkness. But not now – right now – when the remembering came to her again, she knew this beginning and she felt sad, because she knew the puppet-man would fail again. She would float incorporeally among the stars, at home in the music she created with them, then there would be…his different light…just before his end came again.

Then…as before she felt surf and warm wind, sand on her thighs, her body wrapped in chain again, and as he always did, the distant faceless man stood playing the same penetrating music that led only back into night…and to the return of the one star.

+++++

Cindy Newbury looked into the camera, blinked her eyes to clear her contacts, then adjusted the ear bud.

“Sound check,” she heard in the bud wrapped behind her right ear.

“This is Cindy Newbury, ABC News, one-two-three–four.”

“Alright, good levels,” she heard while she turned again to look out at this fantastic scene. A gymnasium, what amounted to ninety percent of the New York Philharmonic and a handful of violinists from Julliard – but also a couple of med students too, one with a violin, the other with a cello. Everyone arrayed around a single hospital bed standing on the middle of a brilliantly polished maple basketball court. A cluster of doctors and technicians stood behind complicated looking banks of medical instruments; occasionally they looked down at the comatose woman on the bed and one of the physicians adjusted leads and wires on her head.

“It looks like a Shuttle launch down there!” she said into her microphone.

“Cindy?” she heard the producer in her ear-bud say, “go ahead and move on down now. Let’s see if we can get a shot of you near her face when the music starts.”

“Right, Stu.” She looked at her cameraman. “Come on, Paco, let’s get to it.”

“Stop calling me Paco!” Gordon Murphy shot back.

“I will when you stop calling me Dingbat!”

“Fair enough, Dingbat.”

They made their way from the stands down onto the polished floor. Cindy saw Tomlinson’s mother, Agnes Parker, and nodded at her as they made their way closer to the bed, then she looked at her watch again, feeling nervous as she did – because everything about this whole setup seemed…momentous – yet also quite absurd.

“Okay,” the producer said, “going live in twenty seconds.”

Newbury settled into place with Tomlinson’s face just in frame over her shoulder.

“Live in five-four-three-two-and go!”

“Yes, Good Morning, Steve, Marcy. We’re here this morning at Columbia University, at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, reporting on what appears to be a very unusual experiment that’s being tried for the first time…

Newbury talked for a half minute; she offered the at-home audience a succinct rundown of the Tomlinson woman’s tragic story, and its immediate neurological aftermath. The television image cut to scenes of the Tomlinson home, the mangled Volvo, a grandmother’s tears, then fresh flowers on three new graves…

“Research here over the past few days has revealed that these neurologic episodes begin at precisely the time her family’s car was struck, now almost nine weeks ago. It was also recently discovered that the woman has been heard singing notes from Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet Romeo and Juliet at precisely that time, but for some reason she stops at exactly one point in the music, and at the same point each time, by the way, before she falls back into the coma. A few days ago, students from the medical school accompanied her on the violin and cello and there was an unusual response; she made it past her usual stopping point but when the music came to an end the woman dropped back into a complete coma. The thinking now is that the intense stimulation of a larger ensemble might evoke a more significant response…perhaps bringing the woman out of the coma.”

(The camera zoomed out, revealing the Philharmonic arrayed around Tomlinson’s bed. The audience heard the morning anchors in their studio muttering about the size of the orchestra and asking for details about how it had been so rapidly assembled…)

“Yes, Jody, that is the New York Philharmonic, a student conductor from The Julliard School is readying them as I speak. She should be…”

+++++

The stars were growing silent now, one by one they shimmered faintly and then went out, and she felt herself adrift, adrift and bereft. Yet she felt different now, as well; she felt altered – her mind felt ordered and full, devoid of all emotion as she studied the stars all around her.

They had been her teachers once. And then they had been friends. And yes, she knew now that they had been watching her, measuring her, and she understood why. Time was now as time had always been; as time had once measured them so had they measured her.

She felt the warmth of the sun on her arms now, the cool sea surge against her feet, yet the chains seemed as tightly bound to her as they ever had. She felt sadness grip her chest again and when she looked back to the stars she felt them receding. They had turned from her, they were indifferent again, their curiosity at an end. They were, she knew, now quite finished with her.

She saw the man on the boat, the piano, her feet sinking into the cool sand, and nothing was out of place…yet she felt something was different this time. The strings? The puppet’s strings! They were gone! He began to play and she settled in to listen, and to sing once again the vast, indifferent music of his spheres.

+++++

“Steve! Marcy! Yes, something’s happening now! As you can see, Tracy Tomlinson has started to sing, and, well, as I’m sure you can hear now – the entire Philharmonic is playing with her, too. And what majestic music this is!”

+++++

Wakeman had been watching rows of EEGs and EKGs and so was not too startled when the music began; he had been watching Tomlinson’s incipient swarm, seen the build-up of energy and so knew what was coming – yet Wakeman, like Somerfield and MacIntyre and all the others that were used to seeing her in a tiny hospital room, was unprepared for the awesome scale of the music that now filled the gymnasium. Compared to what had been produced in her room, the orchestral response went beyond overwhelming; the plaintive lament of the strings was crushing in its willful intensity – the music that filled the gymnasium now did so with an almost palpably unbearable emotional intensity.

And those who could watched as Tomlinson sang as before, willfully, soulfully, and with a purity that stunned even the onlookers from Julliard.

Gordon Murphy, the cameraman, walked carefully around Tomlinson’s bed, recording the disparate elements of the scene: Tomlinson’s mother and twin sister – their features trapped somewhere between pain and hope; the two medical students – Somerfield and MacIntyre – doing their best to play with some of the finest musicians in the world; Wakeman – lost in the glow of dancing dendritic impulses and the ever-evolving music inside this poor woman’s wounded brain…

Somerfield felt the music building – not in intensity, because this piece was as far from bombastic intensity as music could be – but building to that penultimate moment, to that gap in time that is to be bridged only once.

“Jody, as you can see now, Tracy Tomlinson is singing, yet her eyes are still closed, but as you can see she is singing with the orchestra, and they are fast approaching that point where her neurologists say the breakthrough occurred! Gordon, can you move in now, get a close-up of her face?”

“I’ll try…”

+++++

The music was the same again. She knew every note of it by heart, yet she remembered how last time the music had been different, how the man on the boat had finally turned to her, and she had truly seen his face for the first time.

But now his music was shatteringly different. His music was full of power, full of celestial resonance, and the notes were beckoning and compelling her to move out into the water toward his boat. She tried to stand, felt the full weight of the chains that bound her even now – but now she struggled to break free of them. She rolled and twisted, fought them off with her hands and feet, and as the rusty links bit into her arms and legs she began to cry, to wail as her frustration painfully began dominate her thoughts, to push aside his music.

Then the music faded, but the man on the boat turned again and looked at her. His smile was as it once had been: warm, welcoming, knowing. Now, the puppet-master’s strings were gone and the man stood; he walked to the edge of the boat and beckoned her with his smile to come to him…

A link shuddered and cracked, and one strand of chain fell away, then another and another. Soon she could stand, but the music was fading now, then it was gone, gone back to the darkness…

She turned to the sky again, and everything disappeared in pure light.

+++++

Judith Somerfield saw it first, just as the music drifted past the dividing line. “Dr Wakeman!” she yelled. “Come here!”

“What – now?”

“Wakeman, get over here!” MacIntyre yelled as he looked at Tomlinson. “She’s crying!”

“What the fuck!” Wakeman was apparently completely unaware of the ABC cameraman by his side.

“You got that right, doc,” the cameraman muttered.

“You getting this, Murphy?” the producer asked Gordon over the headset.

“Yeah – got it. Dingbat, can you get in the shot?”

“Right behind you, Paco.”

Wakeman was looking at Tomlinson; he saw her body shimmer and turn translucent and golden hued, her form surrounded as if by mist one moment then clear and pure within the span of a single heartbeat, and in this cascade of moments her form turned solid and as human as everyone else in the room. Wakeman had the impression, for a moment, that her body in the bed glowed like pure white gold, like light was being born inside her body and reaching out into the world of man for the first time. Then the light became fiercely brilliant, flooding the entire gymnasium with searing white light.

Tomlinson sat up in the bed and one by one members of the orchestra fell silent; some stood and looked at the figure in the bed, others turned away from the light and covered their eyes.

The light pulsed even more brightly for a moment – and then went out; all that remained now was Tracy Tomlinson. Wide-eyed, scared, confused, and totally alone, she turned her head and looked around the room. The people around her in the room were totally silent, the air filled with an immeasurable dread, and as suddenly she recoiled from hundreds of staring, disbelieving eyes.

“You’ll pardon me for not standing,” Tomlinson finally said, “but I can’t seem to get these chains off my legs.”

Somerfield and MacIntyre high-fived; Wakeman joined them and soon a huge gaggle of squawking physicians gathered around Tomlinson; there were a few hugs, yet all the physicians were looking at the woman in the bed as if something more than unexpected had happened.

Because it had.

Soon everyone noticed that Tracy and her sister were looking at one another, that a sort of contest of wills had developed and was building in intensity right before all their eyes. Wakeman felt what happened next – as a sudden surge of power coursed between the sisters. ‘This is like lightning,’ he thought, as the surge passed from the two sisters and then poured through the building. Medical monitors flickered in the overload, then winked out in a single cascade; Murphy’s video-camera flickered and went out, and in the next instant light-bulbs in their ceiling fixtures exploded, sending showers of sparks down on stunned musicians and all the other perplexed onlookers.

As the room fell into darkness, Tomlinson’s mother turned and caught her other daughter as she fainted and fell to the floor. And then she felt Becky’s body; it was icy cold so she cried out for help. When she felt patches of ice forming on her daughter’s arms and forehead, she screamed.

+++++

One week after her awakening, Tracy Tomlinson was discharged from the hospital. Todd Wakeman and the two medical students visited with Tracy that morning, rode down with her in the elevator and walked with her to her mother’s car. It might have been an emotional parting but for one simple fact: Tracy Tomlinson now appeared devoid of any and all emotion.

For the past week the physicians attending her, as well as the medical students on rotation through neurology, had struggled to explain the intricate workings of the brain to Tracy’s mother and twin sister, but in truth they were as much in the dark as anyone. They simply couldn’t explain the profound absence of emotion with any degree of certainty. In all other respects Tracy was neurologically intact: her motor skills were unimpaired, her reasoning ability seemed, if anything, to have improved. She was, for all intents and purposes, unchanged – but for two things.

The first, the barren emotional landscape Tracy now inhabited, had become apparent when she didn’t react to the news of her family’s death. Her response was limited to a few rapid blinks of her eyes. Wakeman was watching and he thought it was almost as though she was preoccupied with something else as the news washed over her; indeed, Wakeman felt her reaction was like a computer busily churning through an advanced computation and was suddenly interrupted and called upon to process something entirely new. The computer ignored the request and returned to processing whatever it was that had preoccupied it before, so while Tracy was functionally intact – she could talk, she could relate and react to those around her – all her interest and conversation was focused now on something unexpected, and startlingly new.

For Tracy Tomlinson was now completely consumed with music.

Yet she had never played an instrument before in her life, had never evinced any interest in music whatsoever beyond listening to The Captain and Tennille or the BeeGees, and that had been decades ago. Music had never been, according to her mother and sister, a part of her life in any way. Not ever.

Yet now she was completely obsessed with music.

On the day after her awakening – early in the morning, in fact – she had demanded to be taken to a piano. Wakeman and Judy Somerfield had been alone with Tracy in her room and had looked at her when she spoke because, as Wakeman would later recall, there was something odd and – he felt – almost desperate in her demand. There was something inside her mind that wanted to come out, needed be given a voice, a means of expression, and Wakeman had called Terry Skinner, the clinical art therapist, to ask for advice; Skinner had come to the room, listened to Tracy, and acted.

They got a wheelchair and wheeled her to the art therapy room; there was a little upright piano against the back wall and Tracy brightened when she saw it. Wakeman wheeled her to the instrument that morning, thinking she must have been a pianist at one time, but when she approached the instrument it was immediately apparent she had never played before.

But Judy Somerfield had, and it turned out she was a naturally gifted teacher.

Tracy hit a few keys, asked what notes they were, and Somerfield sat beside her on the bench and played simple scales for her, showed her how to move her fingers from note to note, chord to chord. After a few minutes Wakeman left Somerfield and Skinner and called for someone with a video camera to come to the room. He called Tracy’s mother at home, told her what was happening, went back to the therapy room and pulled up a chair and watched. He’d heard of some instances of musicophilia occurring after prefrontal trauma; generally these cases occurred after electrical events like a nearby lightning strike – though very little personality distortion was typically observed in these cases, beyond obvious lapses in memory of the precipitating event.

But this was different. He moved closer to the piano and watched. Tracy asked questions; logical, focused questions, not the questions of a damaged brain. Within a half hour she was playing simple ditties, nothing complex, but she was playing them precisely and without any errors. Then:

“How do you write down these notes?” she asked Somerfield.

Judith began by verbally sketching out the structure of musical notation, then illustrated the concepts on paper.

“You were just playing ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star’; this is how you write it out in notes…” Somerfield placed the notes on the paper, then played them one finger at a time while she pointed at the notes on the paper. “See? Easy!”

“What about chords?”

“You really want to get into this?”

“Yes.”

Somerfield turned to Wakeman; he nodded his encouragement and Judith took the paper and wrote out a couple of chords and showed how individual notes were grouped structurally to form various chords. “Here, I’ll play a chord and you try to write it out for me.”

She played a basic C major and Tracy wrote it out accurately and Somerfield looked up at Wakeman, her eyes wide, unbelieving.

“That’s good, Tracy,” Somerfield said. “Why don’t you play some on your own for a while? Try to write down the chord. I’ll be right back.” She nodded at Wakeman, indicated he should meet her outside in the corridor.

“What is it?” he said when they were out of the room.

“You’re kidding, right?”

“No? What are y…”

“Dr Wakeman, she’s like done four or five weeks worth of steady piano lessons in less than a half hour, but that’s only the half of it. She understands music implicitly. I think this is…I don’t know…I think she’s a savant of some sort. Now. But why now? We need to get a real instructor in here. Have an instructor evaluate her. We need to understand these changes before we can figure out what caused them, right?”

Wakeman thought about what Somerfield was saying. Some instances of a priori music skills had been talked about in research derived from hallucinogenic studies, but researchers generally felt the idea was little more than some sort of bogus New Age hooey. If in fact Tomlinson had not had any musical training – of any sort – this might represent some kind of . . . what? Metaphysical event? Or spiritual? If so, what kind of reawakening was this? And where had Tomlinson “been” while she was “out” – because being in a coma meant that was impossible? So, where had she learned all this?

“I’m going to call Julliard. Balin. And I want you to stay with Tomlinson; as soon as she gets tired let’s get an encephalogram. I’ll put it in the chart; you just be ready to move.”

“Right. But…”

“But what?”

“What if she doesn’t get tired?”

+++++

Wakeman hadn’t thought it possible, but Tracy had been playing the piano almost non-stop for a week when he walked her down to the car. She’d exhausted three instructors from Julliard over three days; each concluded before they left that they had never seen anything like this. Ever. The last one, a temperamental man with a reputation for brilliance had been overwhelmed:

“At this rate, inside a month,” Dr. Podgolski said, “she will be the best pianist in the world – within a month. This is impossible, I know, but this will be, even so.” The babbling, flustered man had retreated from the ward and vowed never to return.

Yet now Tracy was going home. Balin had arranged for students and instructors from Julliard to be with her as often as possible, and these students – who all seemed incredibly interested in her progress – wanted to spend as much time with her as possible. They had heard the stories Podgolski told and they all wanted to be a part of this – this awakening.

And through it all, through all the week’s lessons, through all the week’s revelations, Tracy had remained as emotionally isolated as a human being could be. It was, Wakeman once said to himself, as if she had grown a heart of ice.

Now he helped her into her sister’s car, reached across and buckled her seat belt. He brushed against her, almost jumped back when he touched her skin.

Because her skin was icy cold. So cold it almost hurt to touch.

He swallowed hard, blinked, and wondered just who or what Tomlinson was, or, indeed, what she was becoming.

“Good bye, Tracy. And good luck.”

She turned toward him, or to his voice, and he shivered when he saw her eyes. They too were as cold – and as foreign – and he hardly recognized them as human. Her eyes were, he felt, focused on something beyond the infinite.

And she seemed very comfortable out there.

+++++

By her third week at home, Tomlinson’s playing was barely human, her skills no longer explicable. Her mastery of the keyboard was complete, her dexterity was now total; students and instructors left her house each evening with looks of bewildered awe etched on their faces. They told their classmates each day of some new milestone or accomplishment reached, and Dr. Podgolski nodded knowingly at each new recounting.

He was frightened of her.

When he could stand it no more, he called Wakeman. He had an idea. Podgolski went to see Tomlinson that night; he brought Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with him; Wakeman and Somerfield had arrived a few moments before the teacher, and Tracy watched as her mother retreated to make coffee before she turned to the strangers in her house.

The old professor talked with her for a while about the nature of music, about the depth of human understanding conveyed inside the very structure of notes and chords, and Tomlinson arched an eyebrow, as if she wondered what he meant.

“Music is about love, about love of life, Tracy. The joy and the sorrow of living as we must, as we are constrained to, within this fragile window between our birth and death. Music alone can convey these ideas to any human being regardless of where they come from, regardless of what language they speak. Music is the truest universal language. Emotion is the very soul of music, as emotion is at the very core of what it means to be a human being.”

When she did not react to this, he gave her the score.

She read through the notes, looked at one passage for a while, then looked up at the teacher.

“This passage? What does this passage mean?”

He had been watching her, he had seen her eyes follow the music to this one crucial point. “It is the apotheosis of heaven, Tracy. It is the soul’s ascension. Do you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Would you like me to turn the pages for you? Would you like to try to play it now?”

“I do not need the music.”

She turned and attacked the piano; music of such unbelievable power and majesty poured forth from the keyboard that it rendered Podgolski speechless. He had seen the best in New York and London and he had known even then he had been in the presence of immortal genius; but now even those performances seemed hollow and impure compared to what he was hearing. He was for a time caught up in the rapturous beauty of the music until he looked at the poor woman; when he saw the truth of Tomlinson’s genius in that moment – when he saw her as she really was – his awe in an instant turned to sorrow. She was as cold and as empty as space itself. Such technical mastery, such apparent understanding, but in the end her display was simply an illusion. There was no joy in her understanding of the emotive structure of music, and no human emotion connected to her mastery.

She was an enigma, certainly, but in the end, a hollow, vapid enigma.

When she finished she turned to Podgolski and looked at him, or at least his way, and he felt the coldness of pure vacuum in her gaze.

“You played well, Tracy,” the old professor said.

“Did I?”

“What does the music say to you, Tracy?” ha asked. “What does it mean?”

“Mean?”

“Yes, Tracy. How do you feel when you play?”

“What was I supposed to feel?”

“It is, perhaps, different for every pianist, Tracy, but when you give yourself over to the music, when you become as one with the notes on the page, many artists feel themselves in the midst of a grand metamorphosis. They feel changed by the experience. Do you feel the same now? The same as you did before you played the piece?”

“Yes.” Her voice was flat, a vast monotonous plain devoid of what Podgolski now wanted to call the human, or the humanity in music. Now he felt alone, isolated and bereft as he sat next to her.

Wakeman leaned forward now: “If you could think of just one word to describe what you felt when you played the music, Tracy, what do you think that word would be?”

“Empty…emptiness.”

“Do you remember any other feelings, Tracy? Since you came back to us?” he asked.

“I feel cold.”

‘And so do I,’ the old man wanted very much to say, but he held back.

“Cold?” Somerfield asked. “How so? Like the temperature?”

“Yes.”

“Have you felt happy since you came home?” Judy asked. “Or sadness?”

“What?”

“Have you felt happiness since you came back? Or sadness?”

“I don’t know.” Tracy’s voice intoned the characteristically flat affect of a psychoses.

The old teacher shook inside at the human tragedy behind those words. He was at a loss. His worldview could not comprehend such genius arising from the void she described, and the sorrow he felt left him shaking and feeble-minded, inadequate to the need before him. He wondered what the physicians felt: Would they feel as lost as he did?

“Can you tell me what you feel, Tracy?” Wakeman asked. “Physically? Not while playing the music, but right now?”

“I feel chains around my legs. I can’t get them off.”

“Chains?” Somerfield asked.

“Yes.”

“Where did these chains come from?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did someone put them on you?”

“I don’t know.”

“Tracy? Does anyone know?”

She seemed to hover over vast plains of indecision when she heard that question. She looked down at the keyboard and played a simple note, then a chord.

“Tracy? Who knows?”

“i do not know his name.”

“This someone, this man, you don’t know him?”

“No.”

“Can he take them off? Tracy? Can this man help you?”

“No. But he will try.”

“He’ll try? What do you mean?”

“He will try to take them off.”

“And? What will happen if he does, Tracy?”

“He will die.”

Wakeman felt a sudden deep chill in the room; he looked at Podgolski and Somerfield. They were wide-eyed, staring at Tracy, lost in the meaning behind her words.

“Why, Tracy? Why will he die?”

Again she looked away, looked inside that place she held close inside.

“Tracy? Where are you?”

Silence.

“Tracy?”

She turned, looked at Wakeman, then Somerfield.

“He must not try. He will not be allowed.”

“Allowed? Tracy? By whom?”

“He must not. He must not try.”

“Tracy… you’re not making sense to me? Who will not allow this?”

“Only the others can take them off.”

“The others…? Who is that, Tracy?”

“The man on the boat will die. The puppet will die.”

“Wait, what? Who put the chains on you? Tracy? Who?”

“I don’t know.”

“What has the man told you?”

“He does not speak. He is a puppet.”

“A puppet?”

“Yes.”

“Is someone watching him too?”

“Yes.”

“Is someone controlling the puppet now, Tracy?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did this other person put the chains on you, Tracy?”

“I don’t know.”

“Can you feel the chains right now, Tracy?”

“Yes. I can hear them.”

“What do they sound like, Tracy? The chains; what do they sound like?”

She bent to the piano and began playing. Simple notes, but a pure melancholy filled the room, and with each new note a picture of human misery emerged.

“This…this music?” the old professor said. “These are your chains?”

“Yes.”

“Oh my God…” Podgolski said.

“No. Not God.”

“Tracy? What?”

She looked away then, looked away as if listening to something, or someone far away.

“Tracy?” Wakeman said.

“Tracy,” Somerfield said now, “what about the man on the boat? What does he do?”

“He was playing the piano, but he stopped.”

“He stopped?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Because it is time. We must write now.”

“Write what, Tracy? Music?”

“Yes. A sonata.”

“A sonata?” Podgolski seemed stunned.

“Yes.”

Podgolski looked at her again and recognized something in her features. He already knew the answer to this question, but he had to ask.

“The name of the sonata, Tracy? What is it to be called?”

“Starlight. The Starlight Sonata.”

The old man suddenly felt very tired, and very, very old.

“Yes,” he said softly. “It must be.”

Everyone turned and looked at the old man.

He was shaking now, and very pale, as if suddenly the room had grown very cold.

He had, in fact, never felt so cold…not in all his life, not even in the camps.

“It had to be,” he said slowly, softly. “But why now? Why you?”

“Because the others are waiting,” Tracy said, before she stood and walked out of the room.

+++++

“She sounds psychotic to me,” Judith Somerfield said as they stepped out onto the front porch. She said so because she didn’t know what else to think…

Todd Wakeman was shook up, confused, and while he couldn’t quite put a finger on what had just happened – he wasn’t ready to jump on the psychiatric bandwagon just yet. “I don’t know about that. She seems somewhat focused and generally intact, at least when the conversation centers on music. But emotionally? I’m stumped there. I keeping thinking her behavior is more like a lesion, or maybe even a minor CVA, but there’s nothing showing up anywhere.” He crossed his arms reflexively and looked away. “Then again, there’s nothing about this case making a helluva lot of sense right now.” He helped Podgolski down the steps, then the two of them began walking down the walk to the old man’s car. “What do you think of this stuff with the music, sir? What did she call it? The Starlight Sonata?”

To Wakeman the old musician seemed troubled and distant; he felt that Podgolski was still sharply focused on what Tomlinson had said at the piano, yet very little of what was said in there had made any sense to him, but then he had seen that sudden change come over Podgolski. What she said had shook up the old man, had apparently made all too much sense to him, and now he couldn’t shake the feeling that Podgolski had seen something upsetting in there. Though the old man still seemed preoccupied, there was more to it than that. He had been startled, knocked off balance, and perhaps that was why Podgolski seemed reluctant to talk now. Even the way he walked suddenly seemed stilted and unsteady…

The old man stopped; he turned and looked up at the sky, at the stars, and a tired smile creased his face. He seemed to give voice to a silent prayer, then he turned to the physician.

“I think perhaps we should have some tea; then we can talk for a while,” he said as the little group gathered around him. “First, you see, there is a story I must tell you. We need talk no further about these matters until we do.”

“Well, God knows I love a mystery,” Somerfield said.

“Good,” Podgolski said with a wry smile, “then perhaps one of you would be so kind as to help me find my car.”

+++++

It took a while to drive back into the city and find a parking space, but eventually the medics and the old musician made it to a bar in the Village. The entry was off an alley, down a half flight of disreputable looking stairs; the lounge was dark and smoky, a jazz quartet played quietly in a far corner. Conversation was muted, and most of the people seated were nursing a coffee or cognac. The air was blue with cigar smoke.

“Wow!” Somerfield said as she sat in an old booth. “This is like the fifties. Too cool.”

“Oh, I don’t know. I understand by 1950 this place had already seen its fair share of the spotlight,” Podgolski said with a smile as he shrugged. “But things thing’s fall apart, I suppose.” He shook his head, tried to ward off the melancholy that had dogged him for hours. “Anyway, I have been coming here for years, and there is usually an interesting crowd this time of night.”

“I bet,” Wakeman said. “I’ve been in the city for ten years and love jazz, but I’ve never heard of this place.”

The old man smiled knowingly. This hole-in-the-wall was off-map, and deliberately so; it had been since prohibition. It was a hideaway, a forgotten corner for musicians to gather and relax, to give voice to their secrets, or perhaps just to get lost in errant thoughts – if only for an evening.

“It’s a special place,” he said, “and if you act like physicians I may get in trouble for bringing you here.” He looked at them with a full measure of seriousness, and when he saw that they believed him he smiled, laughed at their easygoing innocence. Irony, he knew, was so often lost on youth. They ordered drinks, Irish coffees, anyway, and sat quietly while each gathered thoughts like sweaters on a cold night. Everything the scientists had seen and heard in Tomlinson’s house now seemed hard to digest, as if it suddenly made no sense. But now each seemed to want to know why music was so central to this mystery?

“So,” Wakeman said when he could stand it no longer. “The Starlight Sonata. What is it?”

“Unfinished.”

“What?” Somerfield said. “You mean it exists!”

“Oh yes, very much so. At least in part.”

“You’ve been working on a piece of music called The Starlight Sonata? Does she… is there anyway Tracy could have known that?”

“It hardly seems possible. The piece hasn’t been worked on in years.”

“How long…wait. Uh, what do you mean – are you not the composer?”

“No. My brother is.”

“And gee,” Wakeman moaned, “I guess, well, I suppose this brother, well, he just happens to be your twin?”

“Of course.”

Wakeman stared at the old man for a moment, then he turned and looked away; Todd was dimly aware that his left eye was twitching and he rubbed it. “Is he alive?”

“Oh, yes. At least I think he is.”

“You think he is? Where is he? I mean, where does he live?”

“On his boat, I think, at least he was the last time I heard.”

“Well, crapola,” Somerfield deadpanned, “this just gets better and better.”

“You think so?” Podgolski said, his voice full of bitter remorse. “Then you need to listen now, and carefully. Listen while I tell you a story. Then you tell me if things are indeed better. I will be interested to know what you think. Yes…very interested. Because I have to tell you, I think I am now growing a little afraid.”

+++++

As Tracy Tomlinson retreated further and further from her feelings, as she in effect grew further removed from the calamities of her recent past, another disturbing yet equally curious metamorphosis was occurring not so far away. With each passing day, Becky Parker, Tracy’s twin sister, was seeming to accrue emotions that were genuinely not her own. She was, in fact, now drowning in a huge reservoir of despair that had flooded uncontrollably into her life after Tracy’s awakening. She had no idea why these emotions had found her, but she immediately knew where they had come from, and that sudden realization had left her feeling weak and very vulnerable.

Yet those who had known the girls when they were children would not have been so surprised. The link between the two girls had always been strong, but over the past few days, after Tracy’s awakening, the torrent of newfound emotion had simply overwhelmed Becky, in effect leaving her unrecognizable to those who loved her. In the girls’ sudden, awkward communion, when Tracy’s and Becky’s eyes joined in the gymnasium, some kind of unknown, perhaps unknowable transference had begun – and had been intensifying ever since.

Something happened in those first moments – when the sisters first saw one another – something powerful and unsettling and emotionally wrenching for both of the girls. As Tracy withdrew from her emotions in those first startled moments, as she withdrew from the power of the vision that had sustained her for two months, Becky had been unwittingly forced into the vortex of her sister’s emotional experience, into the very center of Tracy’s confusion. She found herself surrounded by her sister’s emotions – yet, they weren’t really her sister’s emotions at all.

And she had remained inside this nonsensical vortex ever since.

All the pain Tracy might have felt about the loss of her husband was absorbed by her sister.

All a mother’s sorrow over the loss of her grandchildren rained on Becky.

All the confusion that one might feel upon waking from an extended sleep came to Becky as if the void was now a waking dream, and as she wandered through this bewildering landscape each day the power of the dream swept aside all other thoughts and carried her along on the currents of her sister’s recent experience. She grew a little quieter each day, a little more passive – at least outwardly – as the force of her sister’s passage overwhelmed her sense of herself.

In the first hours of this metamorphosis, Becky was riven by the inexplicable undertow of emotion that came to her, yet with each passing day she slipped deeper and deeper into the star-scapes of her sister’s ongoing dream. And yet she remained curiously apart from that other world in one crucial way: she remained consciously aware of her “true” physical surroundings. Now, each day she struggled to keep the two apart – she was slowly losing this struggle. She tried to function normally, to eat and bathe and care for herself, but with each passing hour she found even these simple tasks harder and harder to perform.

Earlier that evening, when Podgolski and Wakeman and Somerfield came to her sister’s house, while Tracy and Podgolski sat at the piano and played the Rachmaninoff Concerto, far away, on the far side of the city, Becky walked into her apartment’s bathroom and looked into the mirror.

And what she saw left her breathless with unimagined fear.

She had reached out then, and she had placed her hand on the mirror…then screamed as she was pulled into the spinning light…

+++++

“I first had the dream,” Podgolski began, “when I was seven. We lived in the Soviet Union, as it was known then, on a small collective plot in what is now Lithuania. A farm, yes – but my family, we were not farmers. We, my parents, my brother and myself, once lived in St Petersburg for a few months, before we moved to a place the Russians called Star City. We grew up, my brothers and I, in a two room farmhouse, and I remember my father telling us we were lucky, even prosperous, to live as we lived. We were Jews, you see. Neither the Germans nor the Russians treated us Jews with great care, as you know, yet my parents survived, as we have always survived. Traditions sustain us, you see. Ah, but we were born a few years after the war, a few days after Israel was reborn, and I mention this only in passing because it was my mother’s greatest hope that as we grew up we be allowed to immigrate to Israel. This did not come to pass.

“I remember most standing by my mother’s side in the afternoon when we cleaned potatoes for our supper; while she worked she told us about Israel, about how good it would be once we lived there. I can still see her, you know, cleaning the skins with a brush, rinsing the potatoes, the numbers tattooed on the inside of her arm. I never knew what those numbers meant, not for many more years, anyway.”

The old man sipped from his mug, his eyes as clear as the memories that now held Wakeman and Somerfield so completely. The room seemed very still; to Wakeman it felt like distant spirits had come to join in this telling of an old man’s tale. Already he was struck by the disconcerting idea that Podgolski had been summoned to tell this tale and that somehow Tracy and her story of puppets and chains was bound up in this account as well. Wakeman looked at Podgolski, at the skin on the man’s hands, wondered just what misery those hands had known.

Podgolski looked down at his hands. “My parent’s desire to leave Russia…well, the political powers, yes? They were less than helpful as it turned out. We were transported to Siberia; my father grew more passive as that my mother continued agitating, demanding of the authorities that we all be allowed to immigrate.” His voice faltered, withered for a moment, then he summoned his courage and continued. “Well, the state had other ideas. But put all that aside for a moment; there is one thing about all this I think important, and that you must know, before I continue.

“When we were very small our father would take us out into the fields at night and show us the stars. He had been an engineer in Germany, their rocket program, but his views on the matter were incompatible with theirs. Anyway, after the war he became a farmer, yet he always loved the stars. He would take all of us out on clear nights and show us the constellations, but always on our birthday he would take just my brother and I out. He would find two stars in the sky, and like they were old friends he would point them out to us. ‘Those are Arcturus and Spica,’ he would tell us, and he told us we could always look up to them on our birthday and they would point the way to Israel. ‘Never forget that,’ he told us. And I don’t think we ever did. At least, not at first, not until Israel became impossible.

“Our Guardians of the State discovered hidden talents in both my brother and myself. We had learned to play the piano, my brother and I, how to write music and how to perform – and we were like puppets on a string, he and I. But it was a very short string. Perhaps ‘leash’ would be a better word.

“He was the better musician, always. His mastery was complete years before I became a merely accomplished musician. In time he would become famous, world famous…”

“Really?” Somerfield interrupted. “I don’t recall a Podgolski…”

“Ah. Perhaps you know him by another name. The name he took after he fled the Soviet Union. Perhaps you’ve heard of Leonard Berensen?”

Wakeman and Somerfield blinked; she was stunned, completely dumbfounded.

“He’s your brother!?”

“Oh yes. If not for him I would have never come to New York, or to Julliard. I came, of course, after the fall of the Soviet Union, long after the film scores and the musicals, after the first three symphonies – and after he became such a wealthy celebrity. He did what he could for me, for a time.” Podgolski sighed as memory taunted him, then he ever so softly added: “Before he ran away from us.”

Wakeman was wide-eyed, incredulous. “I’m sorry – but what about the dream? Where does that fit into all of this?”

“I think perhaps I’ll have a whiskey,” Podgolski sighed. “Would either of you care to join me?”

They both did, as it happened.

+++++

Tracy Tomlinson sat behind the piano again; she was silent now, alone with the music that held her attention so firmly. She leaned over the keyboard, pencil in hand, furiously put notes and chords to paper, paused from time to time to play an unfamiliar chord or work through a difficult passage. She could hardly remember Podgolski now, or the conversation she’d had with him earlier that evening. Her mind was filled with music and light, her every waking moment dedicated to listening to the music of the chains she heard so clearly – and to transferring the sounds she heard into notes on this paper.

She rarely stopped to eat or drink, and she did so only when her mother came into the room and insisted. This body seemed immaterial to her – it was a transient thing, little more than a medium of expression, and she resented the demands this thing placed on her time.