It IS that time of year again, isn’t it? Christmas trees and eggnog, chestnuts roasting on an open fire and, of course, ruptured credit cards. But perhaps it’s better to focus on these things now, rather than on political events. Moral decline seems so pointless, so endlessly, nauseatingly pointless.

SO…we have a new puppy this winter, yet another Springer to add to the pack, and she’s adorable. After we lost our precious Heidi we kind of fell back on Suzy, Heidi’s daughter, to get us over the chasm, and it worked. Suzy is literally almost identical to Heidi, and yes, in every respect (she’s a true empath). Yet Suzy is also seven going on eight, and time marches on. She was (is) still (just) young enough to birth another litter and the idea of losing the last part of Heidi when Suzy leaves us has been closing in on both of us. So, to make a long story even longer, when Suzy went into heat recently we sent one of our boys out to do the hunka-chunka one more time, and lo! Suzy was pregnant! Amazing how that works, isn’t it? At any rate, Suzy gave birth to one, yes, one pup, a tri-color girl we’ve named Bonnie. Assuming an average life expectancy of 12 years I’ll be long gone by the time Bonnie checks out, so I’ll have a part of Heidi with me ’til the very end. I don’t really know why I find that comforting, but I do. I guess because there’s hardly a day goes by that I don’t think about Heidi, or Finch, or Ode, or Scout. My life has been bookended by Springers, and what a thing that is. Heidi was such a great pup and I loved her something fierce, but in their way they all have been. We took Bonnie in for her first shots this week and it was the first time I’d been back to the vet’s office since we took Heidi in for her last visit, and all those memories came back in an unwanted rush, but that’s they way of it, sometimes.

Anyway…c’est la vie.

I stopped writing this part of the story after about 20 or so pages, so not a long chapter for you today. Still, the story just reached a natural stopping point, so there you have it. Call it time for one cup of tea? And that means att least two more parts to reach an end…?

We shall see…

Music? Well, yes, but let’s just skip the Tony Bennett Christmas music this year, okay? That doesn’t mean we’re not listening to music as we write (sorry, that’s just not possible), but that does mean – no Christmas Muzak…! That said, the Beatles Anthology 4 dropped recently, and I recommend setting aside a few hours to trip down bluejay way with the lads one more time. This release includes a lot of studio takes, complete with the boys talking about how to do this or that and it’s just a blast listening-in, because it’s a fly on the wall sort of vibe. This release is NOT your usual polished, overproduced Beatles album, not this time around. So, it’s fun and that’s what I’ve been listening to while writing. Now and Then.

And also, a brief note about the Moody Blues. I read an interesting piece in Rolling Stone last week about Justin Hayward, titled The Last of the Moodies, by Andy Greene. The piece was more an interview with Hayward than a summation of the group and/or their music, but there WERE a ton of insights into the group’s internal dynamics. As Hayward was arguably the most influential member of the group, and as he is now the last surviving member, I took the time to walk down memory lane while I read this piece, and if you were around in the late 60s to early 70s you might enjoy this bit of reporting, too. I feel certain your local librarian will help you find the article if you can’t access the piece online. It might be worth your time, Stephan.

So, t-t-t-time to r-r-r-read…! Onward then…!

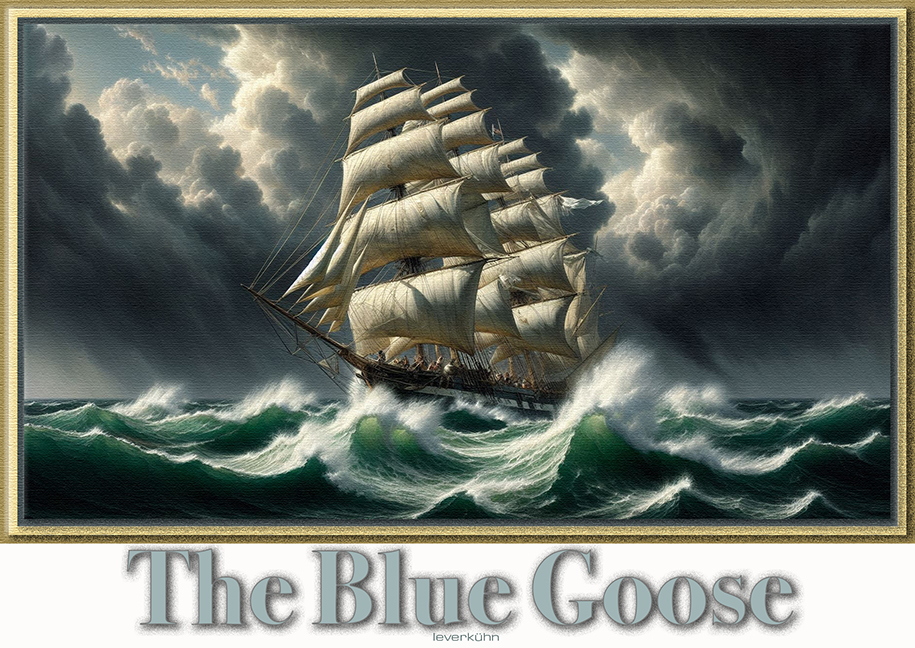

The Blue Goose

Part Three

The disorientation he experienced was just as bad as it had been on his first journey, when Hank had found himself on Pegasus, then anchored inside the lagoon just off the atoll called Tarawa, but the entry in the logbook he had just been reading ended near midnight, just after the very first Pegasus had tied-off in Hull, after completing a short trip to Antwerp and back. The captain, his great-great-grandfather Eldritch Henry Langston, Sr., had made a small error in timing the incoming tide, just as Pegasus approached the Humber Estuary, and Pegasus had struggled for hours to gain the commercial wharf on the north side of the river right off High Street, but she was tied-off and most of the crew had gone off in search of a good time.

And after standing at the bathroom mirror, this was exactly where Hank was now standing.

The cobbled street was slick from the dense fog that had settled over the town, and it seemed that most everyone that lived near the waterfront had long since retired for the evening. Hank turned and looked up the street, his eyes drawn to movement in the shadows, perhaps, or was it the mayhem coming from a drinking establishment down the way, closer to Pegasus? His curiosity seemed to tell him to focus on the noise coming from inside the pub down the street, yet his instincts were telling him that he was surrounded by danger.

So he focused on the shadows, letting his eyes adjust to the darkness.

Yes! There! Two men hiding behind a barrel, crouched down low as if hiding, and they were staring at him.

The hair on the back of his neck was standing on end now, and about the same time he remembered reading in the log that it was cold here in March – and so realized that he was woefully underdressed for the moment. He was wearing a windbreaker, one of his father’s actually, a dark blue jacket that identified the owner as a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy. Hank was now almost tall enough to wear the jacket without rolling up the sleeves, but his father weighed quite a bit more so the fabric hung loosely on him. He was wearing a red t-shirt under the jacket, and the same jogging pants he’d been wearing since Friday. And, of course, a new pair of blindingly white Adidas tennis shoes. In other words, he looked just like any other kid in America – only from two hundred years in the future.

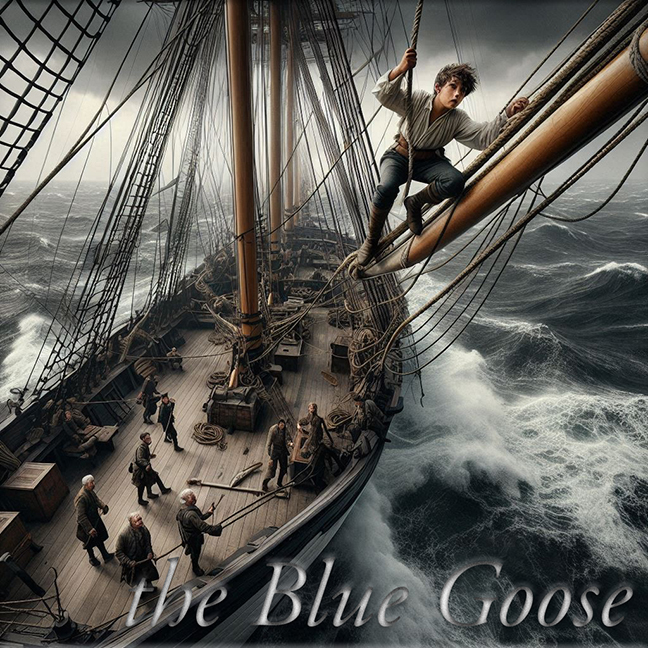

But his father’s windbreaker wouldn’t protect him from two men intent on attacking him, would it? He turned and started walking towards Pegasus, and the two men broke cover and started following him, picking up their pace when they realized their intended was now walking to the ship on the wharf.

Hank picked up his pace again, then he began jogging. The two now gave up any pretense of trying to hide and began running after the boy…but Hank was faster. Not as fast as his brother Ben, but fast enough. He was perhaps 100 yards from Pegasus when two more other men stepped out from behind a small shop just ahead, and these two were now blocking his way. Hank suddenly realized that the first two had been herding him, forcing him into the trap the four men had set for unsuspecting victims – just like himself.

He shuddered to a stop. Trapped. And the four men knew it, too.

They started taunting him as they closed in, and Hank saw that one of them had a long dagger, another had a small club dangling from a lanyard around his wrist. Hank looked towards the water, thinking he might make a jump for it and try to swim away from the trap – but the tide was obviously out and the water appeared quite shallow. And in the other direction? Nothing but shops and warehouses, packed so close together that most appeared to share common walls.

He couldn’t run and he certainly couldn’t fight four armed men, so he relaxed and decided two wait for an opening before making a break and running from them.

One of the men, the one with the dagger, was making kissing sounds with his lips, taunting Hank as he came close, saying he was going to take him in the arse – whatever that meant.

But just then a man in uniform stepped from the shadows and walked over to Hank.

The man was wearing a seafarers uniform, and apparently the man held high rank. He was tall and thin, but then Hank saw that the man also had a pistol of some kind in his right hand. He was holding the weapon in such a way that all four bully-boys would know they were approaching an armed man, and an officer at that.

The man with the dagger hesitated for a moment, recalculating his chances as this new threat emerged, but then he smiled and came on again, deciding to press home his attack.

The officer held the pistol out at arm’s length and cocked the firing mechanism, and still the attacker came on; on seeing this, however, the rest of the gang began melting into the shadows.

As the lone attacker closed the remaining distance between them, the captain leveled his weapon, now pointing it directly at the assailant’s face. And then the bully-boy stopped, his head cocked a little to one side.

“Captain? That you, sir?”

The pistol dropped a fraction and the officer peered into the fog. “Nicholson? What the devil are you doing out here?”

“Aye, we was just havin’ some fun, skipper…”

“Indeed. I suggest you go look for your amusements elsewhere. Now.”

“Aye, sir.”

And the bully-boy walked sheepishly away down the slick cobblestones, leaving Hank and the officer standing there in the middle of High Street.

“You certainly chose an odd time to come along,” the officer, and Hank’s greet-great-great-grandfather said.

“Henry?” Hank sighed. “You’re Henry Langston?”

“Aye, that’s right, boy. Now come on, let’s get you down to Pegasus, and me out of this cold.”

Hank now felt at ease enough to take a look around; he recognized the Holy Trinity Church from Google Earth just a few hundred yards away, but nothing else looked familiar. The waterfront was a loose collection of wooden wharves and shacks on spindly piers, and many appeared quite worn down by both time and tide.

And wind!

The wind down here on the exposed waterfront was howling, and it was cold, too. And the air was damp, Hank realized, then remembered that high humidity made extremes of both heat and cold more uncomfortable.

And Pegasus!

This wasn’t the sleek schooner he’d been aboard at that atoll. Called Tarawa, he remembered. No, this ship looked more like something out of that Russell Crowe movie. Master and Commander, wasn’t it? Fat, tall, two gun decks, three tall masts, the center mast the tallest, and with a bowsprit that jutted way higher than the sleek-lined schooner’s had. This Pegasus looked twice as fat as that schooner, too, and probably had twice the complement of crew, too.

As they approached the gangplank, Hank thought the crossing looked unusually dangerous, like a couple of boards slapped across the gap between the main deck and the seawall, and it had to be twenty feet, maybe even thirty, down to the water. Hank had never been especially afraid of heights; then again, he’d never had to walk across anything like this before.

And yet Henry walked right out onto the gangplank as if he was out for a Sunday stroll; Hank got to the threshold and stopped, and it was all he could do not to look down into the abyss thirty feet below…

“Here, boy, just look at me. Don’t you be looking down, not’t all. That’s right. Look at me, then a few paces ahead. That’s it, that’s a good lad.”

Hank’s few steps on the oak planks felt okay – probably because the plank wasn’t deflecting too much while close to the seawall, but by the time he was halfway across, the plank had deflected a lot – at least a couple of feet, and Hank felt queasy when he realized he was walking on something that could break at any moment…

But nothing broke. The wood didn’t make a sound, not even the slightest creak, and Henry was regarding him with a wry, knowing smile.

“You’re not the first to have a problem crossing, boy. Don’t you worry. You’ll get used to it in no time.” And with that, Henry turned and walked aft to a low doorway under the poop deck that led, apparently, to officer’s cabins, or rather a long corridor with tiny, cubicle-like cabins on both sides of the narrow hallway, the very low-ceilinged passage only dimly lit by two small, flickering oil lamps. Hank heard loud snoring coming from a cabin and at first he thought this must be a cattle pen, then he heard a long, low rumbling fart followed by a satiated, lip-smacking moan. Then the smell hit.

And he retched. Involuntarily. Something about the combination of body odor, rank feet and that fart got to him, and Henry shook his head as he ducked low to enter his sea cabin. It was even darker inside this cabin, even with the white-washed ceilings above the heavy oak timber beams overhead. Hank could just see a fairly large table under the arched row of windows across the stern, and two men were sitting there, apparently waiting for their captain…

But as his eyes adjusted to the dim light in the cabin he blinked several times, as if he couldn’t believe what he was seeing.

Because he saw both his grandfather – and his own father sitting there, waiting for him.

And so was Gertrude. And even she seemed to be enjoying this little surprise…

+++++

Elizabeth Langston woke in a cold sweat, yet she was sure she was still dreaming.

She had been watching her son almost from above. He was standing on an old cobblestone street, and four men were surrounding him, closing in on him, and she had tried to scream, tried to warn him…

…but then that silly blue goose had come into her dream…

…and then the goose had come right up to her and stared into her eyes. Her coal black eyes almost seemed lit from within, and suddenly she was sure the bird was trying to tell her something…

Then through swirling mists she saw the officer with the pistol and then she knew her baby boy would be alright.

+++++

He could hardly sleep here. The noises all seemed so unfamiliar, but the smells were truly awful. Like the locker room next to the gym at school, only ten times worse. And then, as soon as he’d crawled up into the tiny sea-berth, he’d felt little creepy-crawly things burrowing into his skin. First on his thighs, then on his forearms. When he was sure something was going for his nuts and asshole he jumped out of the berth and started picking at the lice crawling all over his legs, then he grabbed his father’s windbreaker and went to lay down on the floor beside the little wood burning fireplace by the chart table. And a few minutes later he felt himself falling asleep.

Maybe he had expected he would wake up back in Rhode Island, but that wasn’t to be the case.

No, Pegasus was making her way slowly from the seawall, and men were running about on deck shouting orders and climbing the rigging and someone was calling out their depth, too. He looked at his Apple Watch but realized it was gone, and when he reached for his father’s windbreaker he realized that it was now gone too, which also meant his iPhone was gone.

“That figures,” he sighed, because he was sure either his dad or Bud had taken them.

Then he realized he had been covered by a blanket some time during the night, and his head had been resting on a small cushion, too. Clothes had been laid out for him on the chart table, everything but shoes, anyway. He looked at his white Adidas tennis shoes and sighed, yet there was nothing he could do about them right now. He changed clothes then followed the noise down the long hallway to the same low door he had entered late last night, then he stepped out into the brightest sunshine he’d ever seen.

He squinted and shielded his eyes with his hand as best he could, then he heard Henry calling out to him.

“Here there! Boy! Come up on deck, now! Come on, let’s not take all day, shall we?”

Hank turned and made his way up the short set of steps that led up to the poop deck, and Henry was waiting for him by the ship’s huge wheel, complete with a large cast iron fitting on the forward facing side that was attached to a heavy chain, so attaching the chain to the wheel. The chain disappeared belowdecks, so it apparently was attached to the rudder – because when the wheel turned the chain ‘turned’ too, and then the ship turned with it.

“You there, boy, get out of the way!” Henry snarled, and he saw that, yes, Henry was snarling at him!

“What do you want me to do?” Hank asked.

“Stand over there and watch! And mind your manners now, boy-o!”

Henry was pointing to a small platform beside a nested mass of rope that almost resembled a sailboat’s standing rigging, except there were no chainplates here, or anything else he was familiar with. And these rope shrouds were as big around as his wrists, too!

He moved to the starboard rail and watched two men forward, both right beside the bowsprit; one was swinging a line with a lead plumb on the end, and the other was calling out the depth under the ship’s keel. He saw there were no markers to indicate the channel, just swirling brown water the color of coffee with a lot of milk in it, so no way to know where the hazards lurking under the water were located. No wonder everyone on the poop deck seemed tense!

He took hold of a line and hauled himself up on the rail so he could get a better view of the way ahead, but a moment later he felt Henry by his side.

“Here, boy, go on up and have yourself a look around, and have yourself a fine old time up there while you’re at it.”

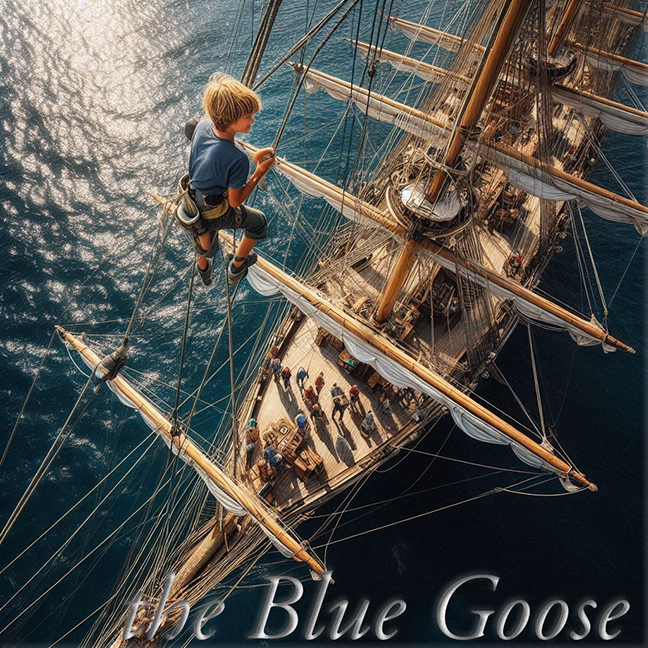

Hank saw Henry was pointing up the ratlines to a small ‘crow’s nest’ where this widespread set of shrouds came to a point, but it had to be thirty or forty feet up there…

“Go on, boy! Give her a try!”

Hank knew this was a test – as he could see the challenge in Henry’s eyes. Maybe there was a little hint of a taunt in there, too, and he didn’t like that so he swung around off the rail, landing hard on his feet, then he walked aft to the stern rail. He found another shroud and hopped up on the rail and looked down at the ship’s gurgling wake, not at all liking this man.

But soon Henry was barking orders at his helmsman, then at someone up on the bow, probably the two men sounding the muddy bottom under Pegasus, so he had all but forgotten about Hank.

What had his father told him last night? “It’s time you learned your way around a real sailing ship, so you’ll stay here until you do…” And it hadn’t been a request, either. And Bud felt the same way, too. His father had never spoken to him like that, never! Only his grandfather seemed to understand why, too. Yet Bud never had to order people around, probably because people respected him, respected the way Bud treated the people who worked for him. But then his father had started barking orders at him, telling him what to do, just like this Henry was doing…and it had upset Hank.

But hadn’t his father told him all about that once before? During his first year at Annapolis? That had been all about learning to take orders from superiors, and then learning how to carry them out – and to the letter – without complaint. Because ships couldn’t function without leaders, and leaders couldn’t exist without seamen to carry out orders. It seemed simplistic to him until he remembered that ships needed leadership or lives would be lost. What had his grandfather always said about the sea? That the sea doesn’t care who you are, only that you respect her? At first he didn’t understand that, but after a few long trips on small sailboats, when he first made it out into the Atlantic, the meaning of that respect became clear. The sea, his grandfather told him after one such trip, doesn’t suffer fools gladly. Hank understood after that. Orders save lives, even if they hurt your feelings.

Was Henry doing the same thing?

Hank turned and studied the ratlines. How and where to put his feet, and where to put his hands. How to steady himself as he made it up to the crow’s nest, because at first glance that looked difficult, but not impossible. But then…he’d need to come down, too. He’d felt queasy on that gangplank, hadn’t he? Because he’d never climbed anything more difficult than stairs. He’d never even hiked up Mount Ascutney, or the big mountains over in New Hampshire. Never tried to climb up even a little rock face. Was he afraid of heights?

He jumped down and walked over to the ratlines and started making his way up, slowly, one rung at a time, deliberately moving a foot up, then a hand, then pulling himself up to the next bit of rope. What had Henry said last night? Don’t look down? Focus on the way ahead?

So of course he did just that. He took a step up, then another…

And after a few steps up he realized it wasn’t all that scary.

So he looked up again and started climbing. The crow’s nest seemed to waver in the sunlight, the ship rolling around, dancing a bit with each step he took, but soon enough he was almost at the platform and so pulled himself up, then stood.

Yet Henry was already there, waiting for him.

“Now, that wasn’t so bad, was it?”

“How’d you get up here?” Hank asked, dumbfounded.

“Well, you know, I’ve done this a few times before, boy-o. And it’s a practical this, a wee bit of skill you’ll need every day. You’ll come to know that you either move fast up here, or you will often times find yourself bleedin’. Sometimes people die up here too, boy-o, because they never learned how to move fast in times of trouble. Bad thing it is to see, too, but we all have to start somewhere. Yes…we all do, and now your time has come. But that’s as it should be, young Henry.”

Henry turned and scanned ahead of Pegasus and then, upon taking a fat shroud in hand, he leaned out over the deck and shouted to the man at the helm. “You there, Mr. Withers, give us ten degrees to port if you please!”

“Ten to port! Aye, Captain!”

“Now, boy-o, come over here and look forward, just to the right of the bowsprit. See that swirl, and how the water darkens under? That’s the tide moving past a rock or a stump down there, and the water turns dark because dangers lurk just under the surface.”

“Okay,” Hank said, nervously looking down at the deck before looking forward.

“And the smooth waters to the left? See it there? Aye, that’s deep water. But when we return, in a month or so, this channel may have shifted some. Do you know why?”

Hank nodded. “Yessir. The action of the tides carries mud and silt as it ebbs and floods, and that movement makes the bottom shift.”

“Oh, that’s right. You been sailin’ a wee bit, have you? Well, good ons you. Less to teach, for me anyway, but things are different here on the Humber than they are when you get out on the sea, right out there,” he said, pointing to the North Sea now just a mile ahead. “When the winds pitch a fit and the waves start talkin’ to you some, well now, that’s when the real learnin’ happens. Got that, boy-o? There’s no cryin’ out there, none a’tall. And we ain’t got time for no cryin’ when the storms come at us, never when the storms come.”

“Where are we going now?”

“Aye, yes, to Hanseatic Bergen for our first stop, then on through the Skagerrak and into the Baltic, where we be going into the Trave River on our way to Lübeck. We be carrying wheat and broadcloth to Bergen, then hides from Bergen to Lübeck, and we’ll return with barrels of beer and our hold full of timber and some iron. We’ll be keeping an eye out for a bit of copper, too. Now…look up.”

“What?”

“Aye, are ye deaf as well as daft? I said look up, there, up to the top of the mast!”

“Okay?”

Henry wrapped his wrist and lower legs around the shroud in his hand and smiled. “Now, follow me!”

And with that the spry old men started pulling himself up the shroud, heading for the masthead.

Hank blinked. He watched his great-great-great-grandfather sliding up the greasy old shroud like there was nothing to it, then he tried to emulate the way the old man had wrapped the line around and through his legs. He tentatively pulled on the rope once, then tried to pull himself up.

And…nothing. He couldn’t do it.

He tried again.

Nothing.

And watching all this, Henry slid down the shroud and back to Hank’s side all in one fluid motion, and once he was beside Hank he felt the boy’s upper arms and shoulders. “Here there, ye got no muscles, boy-o! Well now, it’ll be one thing at a time…so first, let’s get you down, then maybe get some food into you…”

Hank looked down, obviously feeling a little low about this assessment.

“Now, there’ll be no pouting on Pegasus, boy. None at all. Anyway, after a few months working up here you’ll be free as a bird, flying all over this rigging, but not today, and not on an empty belly!” Henry slipped down the shroud to the poop deck and walked off, shouting at the men up on the bow. “Hey there, Killigan, keep them calls a-comin’ now, will you?”

Hank looked ahead, then off to port at a little village that had a magnificent steeple jutting skyward, hovering there just above the village and he thought it must be an obvious reminder of faith to seamen coming and going. It had to be a parish church for it was too small to be a cathedral, but the structure was handsome – and it looked strong, too.

“Not like me, that’s for sure,” Hank sighed. The thought of sliding down that shroud like Henry just had filled him with foreboding, almost pure dread, and he just knew if he tried to do the same he’d fall down to that deck and break every bone in his body…

…so his hands found the ratlines and he climbed gingerly out there until he was balanced on the braces, looking down at the deck and feeling his muscles freeze and knot-up…

…but he forced himself to move…

Left hand down a rung, then the right foot. Right hand, left foot. Down another rung in white-knuckled fear, grasping his way down to another rung and another…until his feet were on that wide, comforting oak, that fat rail atop the sheltering bulwarks, and from there he hopped down to the deck, beaming at his accomplishment.

But no one was paying him the slightest bit of attention. Not even Henry.

He sighed then looked down into the swirling water, and Henry came by a few minutes later and put his hand on Hank’s shoulder. “Here now, go on, get some breakfast in my cabin, then we’ll get you a bunk with the other midshipmen.”

“I’m not really hungry yet…”

“Well, you soon will be, son. It’s blowing holy snot out there, and just as soon as we pass Spurn Head we’ll be in the thick of it. You eat now ‘cause you might not want to again for days, and it won’t do to have you dyin’ on us, now will it?”

“What?”

“There’s no goin’ back, boy-o. No lookin’ in the mirror and duckin’ back to the comforts of your grandfather’s boathouse. No, you be goin’ back in a year or two, or not at all…”

“But…”

“No buts now, boy-o. No, you go and get yourself some food – or I’ll put you right to work, and now…”

+++++

She was adrift. Adrift in time. Unmoored from the moment, drifting away from the pain.

As she always did. As she always had, drifting from the pain. The pain of this one everlasting moment in time. The pain that never went away.

She had found the door once quite be accident, and then she had opened it. Once inside, once drifting away, she had learned how to escape. Escape from her father, from the needy intrusions of his warped, grubby needs. She had learned soon enough that she could drift away anywhere she wanted, even away from him.

She felt the straps binding her wrists, and her ankles, yet these were nothing new to her. She had been tied down and beaten for as long as she could remember. Beaten for no reason. Beaten because her pain amused him. Her blood amused him. So she had drifted away, opened the door and drifted.

She saw her baby high above the sea, the raging sea, and she saw the fear in his eyes. Fear, but no pain, and she smiled. She did not want him to feel pain. He was still too young for pain.

Fear was, after all, a firm, if patient teacher – for those willing to learn.

+++++

The sea is a firm teacher, even though she is often more than a little impatient. Eldritch Henry Langston was a firm teacher, too, and he did not suffer fools – gladly or otherwise. He explained a thing once, and you either listened and learned or you suffered the slings and arrows of the sea’s impatience. Depending on what you were doing at the time, this might mean the merest embarrassment, or it might mean instant death. Your own death, and others too. To the sea, it made no difference. You ate when you had time or you did not eat, often for days. The same with sleep – take it while you may. When you were told to climb the foremast in a gale to secure lines that had come loose, you did so or the mast might come down – and all hands on board might be lost.

Hank began two understand that life on a ship was not the same as daydreaming in middle school. That he could not tune out the teacher and daydream because he wasn’t all that interested in split infinitives or what happened in 1066. He was also beginning to understand that inaction held consequences as dire as actions poorly performed, too. He watched what happened to the laziest among the crew, to the not so gentle ostracisms, then the shunning, and he vowed not to ever become that sort of person. He wanted to be thought of as someone that could be relied upon to do the job right the first time. Like Henry, just like Henry.

Maybe that’s why his father and grandfather had come back here, to Pegasus – and to Henry. Maybe they wanted to help him understand the absolute gravity of personal integrity. People are attracted to integrity, just as they are repelled by its opposite. But Hank’s life, up to this very moment, had no context. He had never experienced what the Langston family was all about. Personal integrity, certainly, but in the end all Langstons had been explorers. But Hank didn’t know the meaning of the word, not yet, because that’s not something that can be taught in school. Exploration has to be experienced before it can be understood, and yet the best explorers are neither leader nor follower. They are guides.

Ian Nicholson, the leader of the bully-boys, was a true seaman and, oddly enough, a patient teacher. Once he learned that Hank was the Skipper’s nephew, he took the boy in hand and literally showed him the ropes. From what they were called to what they were made of. He taught Hank how to splice lines. How to tie knots with lines. How to climb lines, hand over hand and with the line leading around the ankle ‘just so.’ Hank began to understand, too, that when he did the job right he gained a measure of respect. Once his mates began to understand that he could be counted on to get the job done, it was like a switch had been thrown: Soon enough he was no longer the skipper’s nephew but a shipmate, and Hank soon realized that there was no finer feeling in all the world.

And he soon loved it high up in the ship’s rigging, and with Ian’s steady hand guiding him, Hank was soon comfortable doing any task assigned up there.

And on seeing that, Henry promptly moved him to the gun deck. And then, a week later, to help the merchantmen with their counting belowdecks or on the wharf in Bergen.

When Pegasus sailed into the Hanseatic port of Bergen, Hank was with the men unloading cargo and the reloading the ship’s hold, learning the intricacies of placement and then securing each item to prevent movement. He spent time with merchants and bankers, keeping an inventory and counting payments. On the voyage to Lübeck, he worked in the galley, then, after they arrived on the Trave, he spent two days with a team assigned to scrub the bilge. He stayed down there until the rancid space gleamed.

And one thing he knew, innately, was that complaining was not an option. If he had to shovel shit, he covered his nose and with his mates he got to it. When he left the bilges cleaner than they had been in years, his mates began to look at him differently, and not one of his shipmates thought of him as the skipper’s nephew after that.

He had been on Pegasus for three months by the time she slipped her lines and eased into the main channel of the Trave, the river that led from the docks in Lübeck back out to the Baltic, at Travemünde. He had tried beer by then, eaten the best sausages ever, and even made a few new friends in the town. He’d been too a merchant-bankers home to dine, and as he conversed with timber merchants from Prussia and Poland he felt a self assurance he had never known as he answered their endless questions about the forests in New England. And when he stood beside Henry as the men made sail, he felt better about himself than he ever had.

“You seemed quite confident last night,” Henry said as he watched the men on the bow swinging the lead-line. “I think you lit the fires of more than one man’s imagination, too. There’s great money to be made in this New World of yours, and you met many who will lead the way.”

“I wish I spoke the language,” Hank said.

“Aye. It’s no good to rely on someone else to translate. Have you not learned the French or the Dutch yet?”

“No, not yet. But I will.”

“When you get back, you mean?”

Hank nodded. “I can’t stay here forever.”

“Aye, well, you could. You can stay for years and years and when you return all will be as it was. No time will have passed there, and you will not have aged. My own son has come back more than once, you know. Your father, too.”

“Really?”

Henry nodded. “Now look, boy, don’t take this the wrong way, but I’d as soon you not go back yet. I know why you might want to – with your mother and all – but if you leave now and come back again, you’ll find no one will remember you. It will be like you were never here.”

“You mean the friends I’ve made…?”

Henry just shrugged. “No. The knowledge fades. You will remember the time you spent here, I will too, but none of the crew will, so stay until you are sure you don’t want to come back. It’s better that way, and for all concerned.”

“Have you ever come to my time?”

Henry shook his head. “No, and I’m not sure that we may. Not one of us has tried venturing into the future, and I think perhaps that the pain would be too great.”

“Oh? Why’s that?”

“Aye, think of it, son. To know one’s future? To see the mark you made? Or worse still, the mark you failed to make…?” He looked away and sighed. “So, you tell me…What good could come of that?”

“What if you could see the mistakes you made along the way? Would you still not go?”

Henry looked down, shook his head slowly. “Isn’t it bad enough that we can do what we do? And you know, boy, you’ll spend many a restless night wondering why this happened to us…because this thing is as much a curse as it is a blessing…”

Hank turned and looked forward, up past the ship’s bow. “Should we start our turn now?”

Henry seemed startled by that and looked ahead too. “Aye, and thanks, boy. Mister Bennett, start your turn now…! That’s it. Now there! Keep to the middle of the channel…”

“Is the middle ground always the safest?”

“Oh, no, not in the least, but I’ve made this passage many times before. The secret to it all, young Henry, is to put everything to pen and ink. Put your observations in both your rutters and the ship’s log, then you can read your notes before making the same passage again.”

“Rutters? What’s that?”

“Aye, the rutters are more personal, son, just your own observations, and they are for your eyes only, too, never to be shared.”

“What do you put in yours?”

“Actual observations, for one, not so much what’s been passed on to me. I keep a record of the course we steered between ports in the logbook, but my rutters contain what worked well, and what didn’t. And more importantly, why things worked, or didn’t. Tides and currents, for instance, or hazards in a waterway. Because of my rutters, I know that around this next bend we will come upon rocks along the starboard reach, unless we keep to the left side of the channel. I know that because I wrote it all down at the time, when I made my first trip upriver. Which brings to mind one last task I have in mind for you.”

“Oh?”

“I’ll want you to stay with me at the helm, and when I make entries in the log or even additions to me rutters, I want you to take me words down, exactly as I speak ’em. You need an understanding of these things, and not just because every captain should. Everything little thing is knowledge, young Henry. Everything, even the littlest thing you might think unimportant. And out here, knowledge is the only thing of lasting value. Knowledge is the only thing keeping you alive, and make that double for a navigator.”

Hank nodded. “Are we going back to Hull after we unload our cargo in Bergen?”

Henry shook his head. “No, no, we’ll make for the Thames with more, for the docks at Greenwich. I’m sure we’ll have cargo to load there for the journey home, as sure as the sun rises.” He shouted orders to men up the foremast, then turned back to Hank. “Now, let’s think about the day we have right now. The future can wait a little longer, don’t you think?”

+++++

Judy Stone looked up from reading the latest reports re: Elizabeth Langston, from Mass Gen, and she wondered how she was going to tell Henry Langston about the latest developments in her case.

Elizabeth simply wasn’t responding to ECT therapy, at least not in any measurable way. She seemed almost lucid after she came out of anesthesia, but within an hour or two reverted to the same semi-catatonic hallucinatory state she had been in before. The only words she had uttered after her last treatment were “Why won’t you just let me die?”

And that time the neuropsychiatrist beside her had simply replied: “Because you’re 38 years old and have children who need you? And there’s nothing medically wrong with you?”

And with that, Elizabeth had simply shut down again. Just like the time before and the time before…

She still refused to eat. Or drink, so her treatment team kept her on IV support. Yet they knew it wouldn’t be long before the woman’s organs began failing, so they had two confront an uncomfortable reality. It was time her family begin looking into end of life care.

And when Judy Stone read that her heart began breaking.

She had made an inexcusable mistake, too. She had grown close to Henry and his family, maybe too close. They had done nothing wrong, nothing to deserve what they were about to go through. And Henry was in the worst shape of them all. Now if anyone asked how his wife was doing he was just as likely to burst out in tears as he was to shrug and look away, and as he had always been the absent-minded professor the change had startled his peers in the department. Now even his students were beginning to avoid him.

And now – she cared. About what happened to Henry most of all, because without his understanding and strength there would soon be four kids spiraling down the drain with him.

So, how would he take this latest news?

More to the point, was it really time to start thinking of hospice care?

She wasn’t sure, and that was why – as soon as she got into work that morning – she called the lead psychiatrist in Boston and asked to come down and observe Elizabeth’s next treatment. She wanted to understand exactly what was – and was not – happening, both during and after her treatments, because she wanted to understand why Elizabeth wasn’t responding. And the strangest thing about all this, she admitted to herself, was that she felt she owed this to Henry and his children. She had, after all, been behind the push to get Elizabeth to Boston – for her to undergo what Henry called ‘shock therapy.’

In fact, no one knew exactly how electro-convulsive therapy really worked, only that it did, in demonstrable fact, result in a significant reset of brain function, often eliminating the most debilitating elements of profound depression, up to an including suicidal ideation. Recent research had also been focused on employing ECT to moderate, or alleviate, the worst symptoms of schizophrenia: the visual and auditory hallucinations that effect schizophrenics. Symptoms vanished in a significant percentage of schizophrenic patients, and more often than not it worked in those patients that failed to respond to mainline pharmaceutical interventions.

But, once again, no one quite understood why, or how.

Massachusetts General was a teaching and also a research hospital, and cases like Elizabeth’s might provide critical missing pieces to the evolving puzzle that is neuroscience. Judy Stone was the first to admit that medicine did not yet have all the answers, but she was not the sort of physician that gave up easily. Indeed, that was why she had gone into medicine in the first place. Physicians, she knew, that were guided by a strong sense of curiosity became the best patient advocates, and usually secured the best outcomes. Unfortunately, this patient’s outcomes would, in some sense, be measured by the amount of collateral damage done to her family. Because of Elizabeth’s steady deterioration, Stone had to balance a wide array of risks and benefits when she worked on taking the next steps.

After she finished talking to Elizabeth’s psychiatrist in Boston she turned in her chair and stared at the painting on her office wall. It was a print, of course, of John Martin’s Pandemonium, painted in 1841 and that she had first seen when visiting the Louvre with her husband. Martin had painted this scene after studying Milton’s Paradise Lost, and Martin had rendered a surreal Neo-classical landscape with Satan standing on a bluff surveying his domain, and in Stone’s mind this painting represented the pure, unrelenting Madness of Hell. And Madness was her enemy, the enemy. The enemy she suited up to fight every day of her life. The enemy that was butchering Elizabeth Langston thought by tortured thought, and an enemy that was making that family’s life a living Hell, on Earth.

And Judy Stone was not about to let Elizabeth slip away. Not without a fight, a real fight.

She stood and walked over to Pandemonium and looked at Satan standing there, so proud of his debaucheries, and it had been years since she’d felt so angry.

“No, not this time, you prick – you don’t get this one. I won’t allow it, so take your God-damned hands off her!”

+++++

Henry was watching the waves coming at Pegasus, counting the time between crests on one hand, and passing swells on the other. He was guessing the waves were ten feet tall, and the swell about 15, but every now and then a sleeper came along and walloped she ship’s starboard quarter. As she was taking a brisk breeze off her starboard quarter, Pegasus was heeling a bit and when that big one hit it had pushed her stern into the wind, causing Pegasus to heel even more. Tom Whitacre was steering and even he had been overwhelmed, yet Hank had been standing nearby and dashed-in to help make the save. Tom and Hank had struggled to turn her away from the wind and just managed to succeed – this time – so Henry called out to the men waiting below.

“All hands, time to shorten sail!”

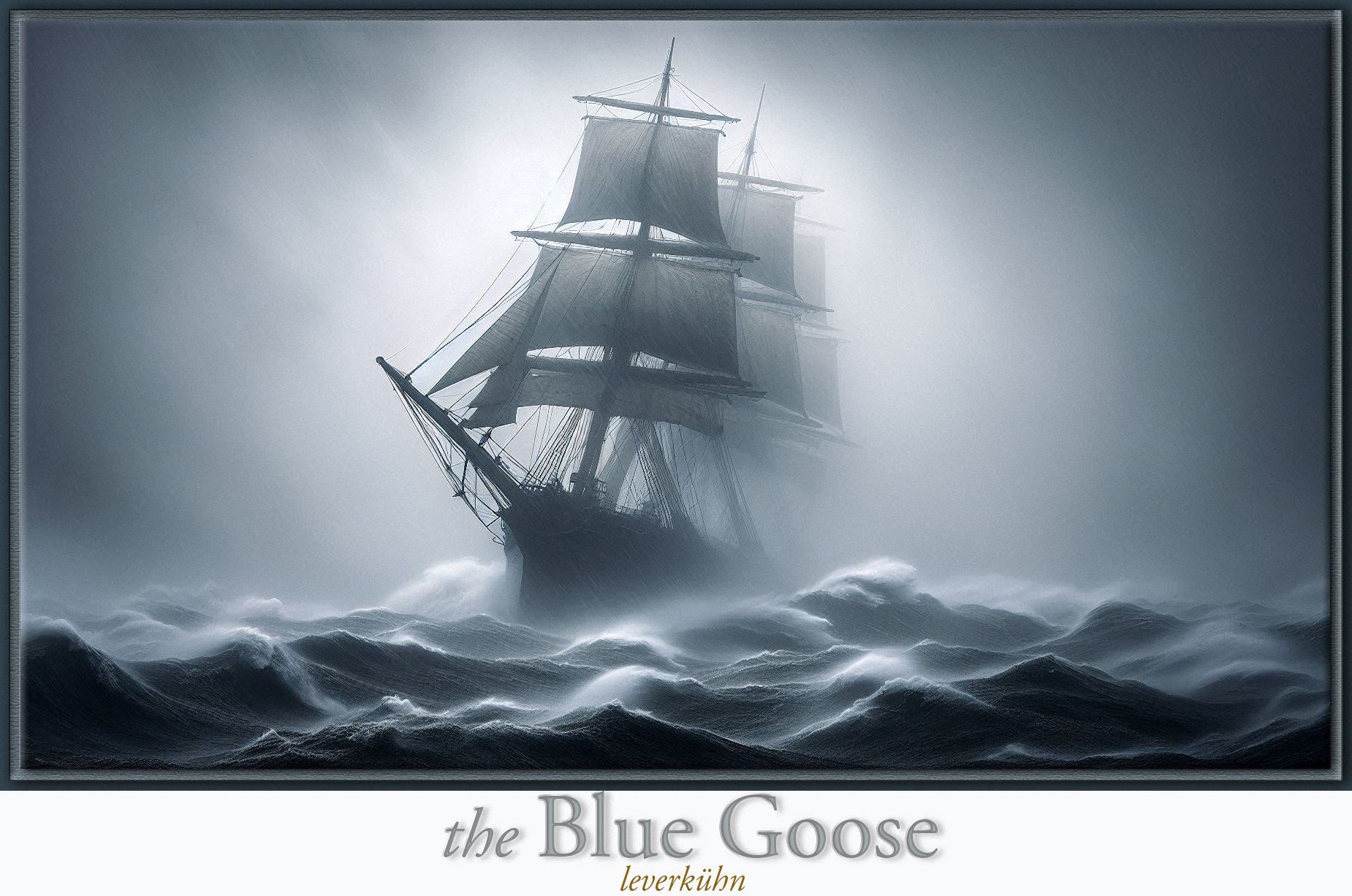

Hank looked over his right shoulder at the wall of dark blue-gray clouds stretched across the far horizon, and any idiot could tell that a big blow was coming.

But what had Henry said? That every voyage has it’s storm?

“Just like life, son. And don’t you be forgettin’ that, neither!”

Now he watched his mates as they took to the ratlines and made their way up into the rigging, making their way out the yard-arms to pull in and furl sail. Pegasus was a fully rigged ship, with a foremast, a mainmast, and a mizzen mast, and her fore- and mainmasts set, from top to bottom, a topgallant sail, a topsail, and a course sail, each flown from stout oak yards. Her mizzen was gaff-rigged, and she flew a gaff topsail in light to medium airs, as well as upper and lower spankers in the lightest breezes. She almost always flew three foresails ahead of the foremast, but once the wind and the seas started acting up it was time to shorten sail, or to reduce the amount of sail area aloft to the minimum necessary to maintain steerage as wave height built. When two men could no longer manage the helm, it was long past time to shorten sail, and Henry chastised himself for making such a stupid blunder. If you thought it was time – it was already too late…!

He’d been watching the barometer in his cabin all morning, and he knew a blow was coming. Now, as he turned to looked at the approaching line of gray clouds, he squinted some, trying to make out details in the clouds.

And what he saw now caused his heart to grow cold with dread.

“Master Henry,” he said to Hank, “perhaps your eyes are better than mine, but look at them clouds. Do you see a strand of white along them, just above the sea?”

Hank looked. “Yessir. It looks like white mist.”

“Well,” Henry hissed between closed teeth, “damnit-all to hell…we’re goin’ t’have a stinkin’ white squall, so a big mother-stinkin’ blow.” He turned to his pilot and shook his head. “Line squall’s-a-comin’, Mr. Pattison. Bring in all canvas and secure the decks and hatches.”

Pattison ran forward and relayed the order and soon everyone up in the rigging knew a white squall was coming, and nothing filled a sailor’s heart with more dread than those two words. Even with all sail down, a line squall, or what some captains called a white squall, was capable of hitting so hard that even the biggest ship could founder under the blow. Ships the size of Pegasus could be blown over on their beam ends, with her masts parallel to the sea, and if that happened water could flood the lower decks and prevent the ship from righting. Henry had been through two such events; one ship foundered, the other had been so badly damaged it had taken three months to get the ship seaworthy again – and that had been somewhere in the islands off the Brazils, with half the crew soon taken by malaria.

They were not halfway to the Thames at the morning watch, so almost abeam Edinburgh – but loaded with timber and iron goods, and with the low-lying Frisian islands now a lee-shore, Pegasus was not in the best position to weather any squall, of any sort. A white squall? No, not at all, because she was too heavy with this load.

“Hank,” Henry said calmly, “you go and check the lashings on the boats, will you? Make ‘em good and tight, boy.”

“Yessir.” Hank felt a knot forming in his gut, a white hot boiling mass of anxiety…as he trotted aft to check on the two longboats…but then, over the moans of freshening winds in the rigging, he heard someone screaming…high overhead…

He looked up, saw someone’s foot caught in the iron ring that carried the gaff aloft…but no one was free to come to the man’s aid…

…but Hank…

…and he went to the ratlines and hauled himself up to the running backstays, then it was hand-over-hand up to the jaws of the gaff… and he found Ian Nicholson hanging by his crushed ankle, blood streaming down his leg and into his face – and Ian looked a mess.

Hank looked down, saw Henry looking up, pointing to the gaff’s halyard and Hank nodded. He swung out, grabbed the halyard and carried it back to the mast, then he braced himself and pulled against the weight of the gaff’s spar. Then, when it hardly budged, he pulled harder and this time the gaff rose an inch or so. Nicholson’s mangled foot was keeping the throat from sliding…so Hank swung out again, this time putting all his weight on the line – and then the gaff shot up a foot or so. Nicholson fell free as his foot slipped out from under the y-shaped throat, and if Ian had not had a good wrap around his wrist he might’ve fallen down to the deck…

But with Nicholson now out of the way of the huge gaff’s spar, Hank let it fall – while controlling the speed with his weight and a wrap around the mizzen. He then helped Ian get back down to the deck, with Hank carrying all Nicholson’s weight in his hands. The surgeon’s mate took Ian when they reached the deck and then, without a word, Hank went aft to check the longboats, while also keeping an eye on the approaching squall…

Which was hardly a mile away now. Three men were working on the main topgallant and unless they got down soon they would be caught up there when the squall hit; he looked at Henry, and Henry was looking at them too, while also watching Pattison securing the last of the deck hatches. He felt gun ports slamming shut underfoot, wedges being driven home to secure them against the sea, all with men shouting, trying to be heard over the rising cacophony of wind and wave.

And then, just before the squall hit, Henry turned and began shouting: “Tie yourself to something, to anything! You there, Hank, tie yourself to the mizzen and hold on tight!”

As Henry’s words registered, icy needles of frozen mist pierced the skin on Hank’s hands and face and he reached out, grabbed one of the mizzen backstays as the full force of the squall slammed into Pegasus’s fat stern. He grabbed a line and fashioned a bowline around the mizzen mast as quickly as he could – just as the wind tore through Pegasus. He felt the ship swinging as if the weight of an invisible hand began pushing her stern, and as her quarters began falling off the wind her bow quite naturally began to swing to starboard, and deeper into the wind. As the ship began heading into the full force of the squall Pegasus began heeling to port; within seconds the squall had Pegasus on her port beam – and then, as the squall caught her and began pushing her beam, the full force of the wind reached her bilges.

And as Pegasus began her lumbering roll…men began sliding down her decks into the arms of the waiting sea…the patiently waiting sea…

+++++

By the time Judy Stone arrived on the third floor of the Wang Ambulatory Care Center at Massachusetts General, an IV had already been started in Elizabeth Langston’s left arm. Elizabeth had been mildly sedated so was still conscious, and she was also visibly angry. She also recognized Stone as she approached, and on seeing her the first words out of Elizabeth’s mouth were: “I hope you rot in Hell, you cunt!”

Yet this was the reaction Judy Stone had anticipated. The reports she’d read the day before hadn’t minced words.

Because this was also the usual reaction Elizabeth spat-out when approached by one of the physicians on her team, and she had little else to say to anyone else. The nurses on her team had also taken to calling her Linda Blair behind her back, after the actress that had portrayed Regan MacNeil in William Friedkin’s film version of The Exorcist. This was not meant as a compliment.

Stone walked beside Elizabeth to the procedure room, and once inside the team double checked her restraints, then the anesthesiologist administered a light general anesthesia. A mouthguard was inserted, then the muscle relaxant succinylcholine went into her IV. Electrodes were then placed on her skull, some to induce current, others to monitor brain activity, then an EKG and blood pressure monitors were placed on her chest and abdomen. When everything had been checked, and then double checked, electrical current was passed to Elizabeth’s brain, producing a seizure. The muscle relaxant prevented any dramatic musculoskeletal movements during the seizure state, which concluded in 52 seconds. The anesthesiologist brought her out of anesthesia and Elizabeth was moved to the recovery center; five minutes later she was conscious and oriented times two. An hour later she went back to her room, accompanied by Judy Stone.

“How are you feeling,” Stone asked when Elizabeth’s eyes met her own.

“I’ve felt better,” Liz said with a chuckle. “You’re Dr. Stone, right?”

“Yup. Do you know where you are right now?”

Elizabeth looked around then shrugged. “I’m…not sure. A hospital, maybe?”

“What city?”

Liz shook her head. “Nope. No idea.”

“You know who the president is?”

“Clinton? I remember Bill Clinton.”

Judy smiled. “How about the names of your children?”

“Hank and Ben. And Hannah. And…is there a Jennifer, too?”

Judy nodded. “Yup, sure is. You remember where you live?”

Liz shook her head, then scowled. “My father? Does he know I’m here?”

“No, he doesn’t, but we don’t need to talk about that right now.”

“Where’s my mother?”

“Probably at home, her home, but you don’t live there anymore.”

“I don’t? Where do I live?”

“With your husband and children, in Vermont.”

“I remember Daisy. And a goose…a blue goose. Her name is Gertrude, and she’s been keeping me company.”

“Gertrude has? How does she do that?”

“I don’t know, but whenever I feel like I’m disappearing she comes to me and keeps me from falling.”

“From falling?”

Liz nodded.

“Falling…where?”

“Our basement.”

“You mean the box in the basement your father kept you in?”

She nodded again. “She comes to me and keeps me from going back there. Sometimes she takes me to Hank.”

“To Hank? And where is he?”

“Right now?”

“Yes. Where is your son Hank, right now? Do you know?”

Liz nodded. “He’s drowning. The ship he’s on is capsizing, but Gertrude is with him now. He’ll be okay.”

“Yes, but do you know where he is?”

She shrugged, her voice growing distant, almost infantile in manner. “No. He’s far away now. Very far away, but Gertrude is with him.”

“And he’ll be alright?”

“Oh yes, she’ll protect him. She’s protecting all of us now.”

“Oh, she is? Gertrude sounds like a very special goose…”

Liz smiled. “Oh, she’s not really a goose…”

“She’s not? Do you know what she is?”

Again Liz shook her head. “No, but I think it’s a secret.”

“A secret?”

Liz nodded. “I’m not supposed to talk about it, am I?”

“I don’t know. Who told you that?”

“I don’t know,” Liz said with a shrug, “but I’m sleepy now.”

Judy Stone watched as Liz appeared to fall asleep, yet it looked almost as if she had been hypnotized. “Liz? Can you hear me?” she asked.

There was no response.

She sat and watched Elizabeth’s vitals reel off on the overhead display, and after a few minutes she stood to leave – not at all sure what that last bit had been about, or even if she should mention it to Henry when she saw him tomorrow. Even so, it was an interesting delusion, and she wondered what Hank’s drowning, and even the presence of a goose inside her delusions, might represent inside Elizabeth’s tortured mind…?

© 2025 adrian leverkühn | abw | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | and this is a work of fiction, plain and simple.