Aye, so here we are again, easing’ into the finale, so to speak. Lots of tangled webs. Lots.

So, the music on my mind while writing? All Things Must Pass, George Harrison’s seminal album. The Who’s Tommy. Peggy Lee’s Is That All There Is. Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left. That’s four decent albums to spend some time in, all worth a listen. Time to cue up some coffee and light a fire? If so, let’s roll on to…

Part Five

She did to know where she was, only that it was dark here. And cold…so very cold.

She tried to moved her wrists, and…she…felt nothing. Her hands moved a little, but not her wrists – and she wondered why. And her muscles ached, especially in her neck. She tried to open her eyes but nothing worked and she began two panic. Kind of a slow burning panic. An awareness that something was wrong, very wrong, more like a new reality laid on top of the old. She couldn’t remember ever feeling this way before, but she did feel a growing awareness that she had very little control over her body. She flexed her toes, then her foot, but when she tried to lift her leg she felt something holding her back. Not a force…but some…thing. A rope, perhaps?

Then a wave of unsettling warmth. Almost like a warm blanket, but not quite. Oppressive heat, then a falling away, as if sleep was coming for her.

But no, this wasn’t sleep, this wasn’t at all like sleep. Her body began feeling pinched and distorted, like the forces of the universe were stretching her body into vast, unfamiliar shapes…almost as if the atoms of her physical body were being stretched out of shape, too – then she realized that there wasn’t a thing she could so about it – so she just let go and fell away, surrendering to the darkness.

And it seemed as soon as she did she felt her eyes open and close. Light danced off her retina, and she felt crusty, particulate sand stuck along the hot margins of her eyelids. And once again she could’t do a thing about it. Someone came by with a cool washcloth and wiped away the detritus on her eyes – and the coolness so close to her eyes felt wonderful. Luxurious. Like she wanted to stop and linger in this sudden release of tension.

She opened her eyes again and looked around the room. More like a cubicle. Medical devices on the walls, beeping and flashing. The light, she suddenly realized, wasn’t bright at all. The room was dimly lit and it felt like she was wrapped-up inside a cool forest glade, shaded by lush, overhanging trees. She recognized a familiar pain in her right arm, in the crook of her elbow, and she could just lift her head enough to see an IV stuck in her arm.

She licked her lips, felt they were dry and cracked, and now she felt the inside her mouth was dry, too. Especially the roof of her mouth. It felt like her tongue was cemented there, and her mouth even tasted hot and dry.

A face leaned over.

It was Henry.

Oh, blessed Henry! Those strong eyes, always so full of courage, and duty. Did he still feel anything for her? After her betrayal? After her many betrayals? She felt herself falling towards the abyss but something pulled her back.

His eyes. His words.

“Liz? Can you hear me?”

She nodded. “Yes…yes…oh, Henry…it feels so good to see you…”

“Does it, babe?”

“Oh, God, you have no idea. Sometimes it’s like you are the only thing left I can hang on to.”

“I’ve come down several times. Do you remember seeing me before today?”

She nodded – but hesitantly. “Sometimes. Maybe. Everything back there feels dreamlike right now.”

“Back there?” he asked.

“Wherever it is they take me.”

The words hit like an icy blast, but all he knew right now was that he didn’t want to follow her down those rabbit holes. “But you’re free of them now, right?” he decided to ask.

And she nodded vigorously. “Oh, yes…and it feels so good to get away from them…even if it’s only for a little while.”

Judy Stone had advised that she might always incorporate elements of her hallucinatory existence in everyday conversations, and there wasn’t much the new, experimental anti-psychotic medications could do about that. After her tenth ECT session she had begun to revert once again, and it was only ‘at the last minute’ that her team gained approval too enroll Liz in the clinical trials for a new class of drug; within 36 hours of starting the new medication her hallucinations abated somewhat. After a week she was speaking coherently for the first time in months, then lucidly about that other world. This, Judy Stone knew, was a big first step. Compartmentalizing those two worlds could lead her to becoming functional again, assuming the intermix of hallucinatory experience didn’t continue to overcome reality.

A month after her last ECT session, and three weeks after starting the new medication, Elizabeth Langston was discharged from Massachusetts General and cleared to return to inpatient therapy at Dartmouth Hitchcock. After her return to New Hampshire she would remain in the care of Dr. Judy Stone – who still refused to give up…

+++++

When she appeared in the upstairs bath, the one off Hank’s bedroom in his grandfather’s house at the boatyard, Judy Stone seemed different. Changed. Perhaps radically changed in unpredicted ways. She and Hank Langston, both of them.

The two reappeared at the same time, of course. Even though the trajectories of their visits had been very different, whatever it was transporting them through time brought them back in the same instant. Hank had been gone for five months; Judy Stone had been gone almost fifteen years. Now, when she reappeared beside Hank she looked almost the same as when she had first stepped into the vortex, yet a closer look revealed subtle changes. Her hair was gently streaked with gray. Her skin was dry, dry as parchment, from living a life at sea for so many years. She had stayed with Henry Langston, Henry the First, and after they departed Hull for France she initially stayed as his guest and friend – but then, more or less, she became his wife. She loved him, and he loved her, but then again he had from the moment he’d first laid eyes on her.

She had never been interested in the sea. Never. Then again, she had never loved a sailor, yet his interests soon became her own. Within a year she had visited Ijuiden twice, and Rotterdam, in Holland. Then Cherbourg and Saint Malo, in France, but soon she fell in love with the western reaches of the Norman coast. Of all the places they had been together, this region seemed to call out to her, to draw her in – and hold her close. They’d been anchored on Pegasus off the tiny village of Port Blanc, in the lee of the Ile aux Femmes on an August afternoon, and even the breezes felt right to her. Existence in the village soon reached out to caress her soul, and nothing in her experience had prepared her for the moment. They were carrying cheeses and wines back to London on that trip, and one afternoon they’d been sitting on the deck just behind the helm, Henry slicing cheese and fresh bread while she poured wine and dreamed out loud. Henry had been so in love, she felt so enamored in the moment, then she had looked around that scattering of islands and known in her heart that she had been born here many times before, and that Henry had somehow always been the most important thing in her life. Now, when she looked at Henry she knew she had always been meant to be by his side. Here, in this moment. There was, she realized, something eternal about that afternoon. Eternal and recurring.

They had sailed together as far as Marseilles, working their way back along the coast of France, then Spain, picking up small consignments of goods to be sold in London. She wandered those ports, even at night, until the ancient airs she breathed became her own, until she felt as though she belonged to this world. They made another trip to Port Blanc and Henry purchased a small house there, just for her. It was on a small parcel of land, good, productive farm land that had been planted with artichokes and cherry trees for millennia.

And they had a baby together. A little girl, Olivia. Judy’s first and only child. She stayed there, in Port Blanc, while Henry made one trip back to Hull, and when he returned he was brimming with excitement. Pegasus had been engaged by one of the large trading houses to sail by way of the Horn to India and Hong Kong, but he would be gone years this time, not just months.

“Can we come?” she asked. “Olivia and me, the two of us? Could we make the trip with you?”

And Henry had smiled. “Truly? You would do this?”

“I would enjoy nothing more!”

And so she had.

Pegasus had returned to Southampton and been loaded with cargo, mainly heavy armaments, and had from there sailed down the Atlantic, stopping in the Madeiras for water, then in Clarence Bay off Georgetown, on Ascension Island, to deliver mail. They made another mail stop at St Helena then sailed directly to Cape Town before sailing on to Goa. After a month making repairs to the ship they had departed for Hong Kong, and when they arrived Olivia was reading and writing and doing her numbers, something almost unheard of for a girl her age.

With her hold stuffed with tea and bolts of silk, Pegasus sprinted home, only stopping at the Atlantic Islands to pick up mail, and on their arrival in Southampton Olivia was five years old, soon to be six.

And after that voyage Henry was a wealthy man. He established his very own trading house and began carrying goods to the New World, purchasing land in Rhode Island and establishing a merchant’s bank in Boston. He carried colonists on one voyage, carrying shipwrights and designers and all the specialized tools to build ships and settling them on his holdings in Rhode Island, and for a year Judy remained with Olivia in France, at their cottage in Port Blanc. She saw Pegasus entering the shallow bay one afternoon and rushed down to meet her husband only to learn that he had passed away just a week before.

Ian Nicholson escorted her to Henry’s cabin and she found him there, laid out on his table covered by two flags: the Union Jack and Rhode Island’s. She sat beside him in the silence, regarding her best friend with eternal warmth in her heart, and she held his cold, stiff hand for hours – then, without warning she felt the pinched distortion begin and she cried out – and inside one drawn out breath she returned to Bud’s house, standing beside 12 year old Hank once again.

She had at once resolved to go at once to Bud’s library and re-read the logs of Henry’s last voyage on Pegasus – but she stopped short, decided against reading anymore details of his life.

‘What’s the point?’ she asked herself. “Was any of this real?”

In the days after her return to Rhode Island, Judy felt bereft and alone, without warning stripped of her only child and her husband, and, oddly enough, now trapped in a time where she felt she no longer belonged. Emily simply could not, and would not accept what had happened to her wife, and the sudden, unexplained distance that had sprung up between them. She felt the pain of this split was too great to bear – even as she struggled to acknowledge Judy’s lack of emotional commitment to their relationship.

Bud listened carefully to Judy, of course, on her return, but he was more than merely curious. She had tasted the forbidden fruit and wanted more, and he listened as any detached observer might as she described the various journeys she had taken with Henry on Pegasus. Bud had been interested, if not exactly engaged, as she described the rich emotional experiences of finding love and, finally, having a child. Of sailing halfway around the world, of working as the ship’s physician, and all the other adventures – some planned, others very much not planned – she had enjoyed. Bud nodded knowingly as he listened, because he had done as much – and more than once – when he was her age. He had never told Ellen, of course, but he had children scattered all over Europe and Japan, from Norway to Marseilles to Kyoto. And though he still visited these children regularly, he had never, not once in more than fifty years, told Ellen – his wife – about these other affairs of his misguided heart.

Then one time, after one of his son’s trips, and after Henry had immediately grasped the possibilities of living what amounted to an infinite number of lives, when Henry stepped out of the restroom he was livid. He had seen into this hall of mirrors, seen impossible lives lived with limitless permutations exploding into view, each iterative reflection incorporating new variables every time the traveller might return to the past. And Henry had immediately grasped the implications: each new trip potentially meant new wives, and new children too, and with each encounter leading to untold suffering when he disappeared. Had his father become a serial husband who’d never developed an understanding of the emotional richness of true love? What he was doing, Henry told his father, was a moral abomination. How many women and children had he abandoned?

His father wouldn’t say. He couldn’t, not really.

After that realization, Henry had adamantly refused to return to any past, and soon he refused to even go down to the library and flip through the logbooks. Any logbook. Perhaps not unexpectedly, soon after he left for Annapolis, Henry began drifting away from his father; when he called home he talked to his mother – and he avoided talking to his old man. But once, during a visit home one year, his father had prevailed on him, asked him to come with him to Hull in the early 1800s, to meet Henry’s little brother, Ben. “Just this once,” his father said, his voice earnest. And yet Henry had heard a faint desperation in the request, almost as if his father was pleading with him to return.

And that did not add up.

And so it was that on a quiet, foggy night off High Street, not far from the banks of the River Humber in Kingston-upon-Hull, and years before the first Pegasus was built, Henry first met a goose, and a blue goose at that. He met Ben but Ben wasn’t what he’d expected. He was very different, yet Henry simply could not remember anything about him. And not long after he met Ben, it seemed as if everything about his life began to spiral out of control.

+++++

“So, show me this boat your grandfather gave you,” Judy said later on their first morning back.

“What? Now?”

“Sure. We’re not leaving until tomorrow morning…”

“Okay, sure. It’s down in the shop, inside.”

She followed him down through the boatyard to the finishing shed, where boats that were almost ready for delivery had their electronics, or other, more specialized options installed. There were four boats in the shed, and two were L-28s, their dark navy blue hulls and exterior teak gleaming.

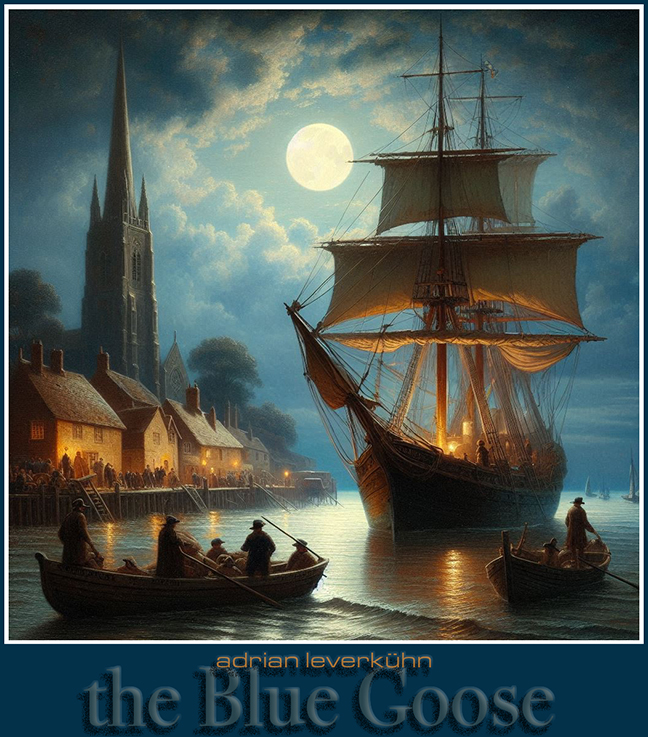

“Ah, the Blue Goose. I wonder where that name comes from?”

“Bud named it. One of the guys carved the name board.”

“That’s a heckuva a Christmas present, ya know…?”

Hank nodded. “She’s something else. We’ll have to use a ladder to get up on deck. You okay with that?”

“Sure. Lead on.”

She helped him carry a large step-ladder over and then she followed him up, watching him carefully as he lifted the companionway boards and went below. He was moving with practiced ease now, so he had developed muscle memory during his months on Pegasus, and she found that interesting. Revealing, and interesting. Whatever else may or may not have happened to them while on Pegasus, their bodies had changed, even if ‘time’ itself hadn’t.

He went to the breaker panel and flipped a few switches, then he turned on the cabin lights, and she almost gasped when she saw the interior. The ceiling was ash, the bulkheads and cabinetry were all teak, and even the cabin sole, the floor, was teak and a lighter colored wood, and the effect was overwhelming. It felt like some kind of womb, or maybe a cocoon, all very warm and protective feeling, but the crew here at the yard also had taste. The satin varnish on the bulkheads, the oiled wood finish on the floor, lights casting pools of warm amber light all conspired to make the interior glow, and it seemed to come alive the more she looked around.

“It feels so much bigger that I expected,” she said.

He nodded. “That’ll change once I start moving stuff aboard. Clutter kills that feeling.”

“You’ve seen that already, haven’t you?”

“Oh, sure. When I help new owners get their gear onboard, everything gets laid out on the cushions and countertops, and suddenly what looked real big looks cramped.”

“And what does that tell you?”

“To keep everything stowed. It’s not only visual, though. It’s safer to move around down here that way.”

“Henry taught me that, too.”

Hank nodded, but he heard the change in her voice, too. “Do you miss him…?”

“Oh, God…I can’t even begin to describe how lonely I feel right now.”

“I’m going to go back to Tarawa. There’s a girl there…”

She watched the change come over Hank as he spoke. His first crush, so of course she had to exist a hundred and sixty years ago, and she wondered what he’d do about it. “That’s kind of a big step, don’t you think?”

He shrugged. “Maybe. I want to see her again. See if I react the same way I did the first time.” He looked around the cabin, and she thought he was imagining where he’d put stuff when he loaded his own things aboard. “What about you? Did you run into anyone like that?”

“I fell in love with Henry.”

His eyes went wide, then he grinned and shook his head. “Ya know, I kinda thought he had a thing for you, but…you had a thing for him, too?”

“Yup.”

“How long did you stay?”

“About fifteen years.”

“Holy crow! Anything else happen?”

“We had a baby, Hank. A little girl.”

He blinked rapidly, as if he was having a hard time with the idea of pregnancy and children, then the timeline hit him. “How old was she when you left?”

“Very young. She was seven, I think,” she said, her eyes tearing up.

“Why did you come back?”

“Pegasus came in to the port where I was living and I found out that Henry had died. Almost immediately I was in the bathroom…”

“You mean…you didn’t choose to come back?”

She nodded. “That’s right. It felt like something, or maybe someone, was watching me. Whatever it was, it grabbed me and yanked me back here, to the present.”

“Damn…” he sighed. “You think you could go back?”

She shook her head. “Who knows. But the thing that bothers me is, well, if there was something watching me it probably won’t let me go back.”

“Maybe my grandfather knows.”

“Maybe. So, tell me about your boat. What do you need to have installed to make her ready to go?”

“Well, I’ve got a water-maker to install, then the wind-vane. I’ll need help with that one.”

“What’s a wind-vane?”

“Kind of like an autopilot, except it doesn’t use electricity. Anyway, the wind steers the boat so you can do other things.”

“Have you thought about what you might cook?”

“Grandma is going to help me with that. Bud recommends we pre-cook a bunch of meals and seal them in vacuum bags, then freeze ‘em up at the house before we carry them down and load ‘em. There’s already one freezer onboard, but we converted a storage cubby into a second freezer so I’ll be able to carry tons of stuff like that.”

“Want me to make you a really good first aid kit?”

“Gee, could you?”

“Sure, but are you afraid of needles?”

“No, not really.”

“Well, I’d need to teach you how to use some things, just in case.”

“Okay. Are you going to go see my mom?”

“Day after tomorrow. That will be right after her last treatment.”

“Then she can come home?”

“If she’s better, yes.”

He took a deep breath and sort of held it, and she knew then that he really was still very worried about his mother. “And what if she’s not better? Then what?”

“Then we talk. You and me.”

“Okay.”

“You know what? I love this boat. It’s super cool.”

“Are you like…from the 80s or something?”

She had a good laugh at that, but something had just popped into her mind. An idea. And who knows, maybe it might even work…

+++++

“How long does its take you to build your 28 footer?” Judy asked Bud.

“Why? You want one?”

She nodded. “I might.”

His eyes narrowed. “Oh? And what are you thinking now, young lady?”

“I want a sailboat. I miss sailing already.”

“Why do you want a 28? Why not a 43?”

“I don’t have a reason, but I like the looks of Hank’s boat. The size seems perfect for me, as well.”

“It is, if you’re single-handing. It gets crowded with one dog onboard, and with two people you start feeling pretty confined. Any more than that and the crew will start bailing out, and you’ll probably go first. So, tell me. Did you do a bit of sailing recently?”

“I did.”

“And you feel comfortable at sea?”

She nodded. “I do now,” she said, grinning.

“Oh? And how long did you say you stayed back there…?”

“About fifteen years, more or less.”

“Uh-huh. And what else happened to you?”

“Well,” she began, “it’s complicated.”

“No, it isn’t. Tell me what happened, Judy. What’s behind all this?”

So, she told him. It was, after all, his family so he deserved to know. So Bud listened and did not appear to judge anything she told him, no matter the subject…until she got to her last moments in France.

“So, you were yanked out of there, just when you found out about Henry?”

“Yes. That’s what I remember.”

“And how old was your daughter?”

“That’s the thing, Bud. She’s fading. Every memory. Every remembrance. Everything I remember about her is fading.”

He sighed, but then he looked away and shook his head. “She’s probably gone, Dr. Stone. And I don’t mean gone as in dead, either. I mean she never happened.”

“That’s not possible. Please, Mr. Langston, tell me that’s not possible…”

He shrugged. “The truth is, Judy,” he said warmly, almost sympathetically, “that it is a possibility. I can’t assign a probability, but you must entertain the possibility.”

“Oh, dear God. No…”

“It’s a terrible thing you’re feeling. Terrible. And I must warn you, too. Don’t do anything stupid. Don’t try to return. There’s a possibility you’ll end up living inside a completely new timeline, and it’s even possible you could find yourself marooned there, with no way back.”

“I wanted a child of my own, you see,” she said absently, her eyes now focused on an infinity that might not have ever existed.

“Surely it’s not too late? You and Emily? Have you thought of adopting, or surrogacy?”

She shook her head, lost in her thoughts. “So, you never answered my question.”

“Which one?”

“The 28. How much would one just like Hank’s cost?”

He smiled, then shook his head. “We have one in brokerage right now. It’s ten years older than his, but it’s still in remarkably good shape.”

“When can I see it?”

“Would next weekend be soon enough?”

+++++

Carter Ash and his son Huck were behind Henry and Hank, following in Carter’s old Subaru southbound on the Interstate heading to Springfield, Massachusetts. There was no snow on the grown now, but the trees were still cloaked in the naked blacks and grays of their winter sleep. Carter was feeling as bleak, regretting the day he’d met Elizabeth Langston now more than ever, because his son was absolutely sure he wanted to go on this hair-brained idea of a trip that Hank was all fired up about. Carter wasn’t jealous, not really, but he wasn’t exactly scared, either. Huck was a strong sonuvabitch, and a real athlete. His balance and coordination were excellent, but his muscle strength was something else. Maybe he might have become interested in football or ski racing, but no, he’d run across a sailing magazine at a friends and had been daydreaming about boats ever since. Far away horizons were calling. Sailboats were calling. And to his son, sailboats made all the sense in the world.

“They’re not just toys, Dad! People live on them, they travel on them, and not just across the country. Didn’t you want to buy a truck camper last year? You said we could go see Yellowstone?”

Carter nodded.

“Well, it’s the same thing, but we could go anywhere in the world…”

“What’s this ‘we’ business, Huck. There’s no we in this, okay. I spent two years in the Navy and I’ve seen what the sea can do when it gets pissed off, and you’re not going to find me out there on a 28 foot anything, let alone a little sailboat like that thing Hank has…”

Huck crossed his arms over his chest and looked out the window. “Weird weather, isn’t it?” he muttered.

“Weird? What’s weird about it?”

“Snow one week. Rain the next. None of the ski slopes open in March, not even out west.”

“That’s why they call it climate change, Huck. We’re finding out that kind of change is unpredictable, too.”

“It was sixty degrees in Newport this morning.”

“I know. I checked. I wish Hank didn’t want to go out this weekend.”

“I think he wants to see how strong the new standing rigging is.”

“The standing rigging? What’s that?”

“The wires that hold up the mast.”

“Oh. Swell. So the things that hold up the mast are untested?”

“Yup, but that’s a good thing, Dad.”

“I’ll take your word for it.”

“Hank’s done a bunch of sailing, Dad. He knows what he’s doing.”

Carter nodded. “Yeah? Need I remind you that Hank is 12 years old?”

“He’s been around boats all his life, Dad.”

“Swell. What about you?”

+++++

Carter and Huck were standing in The Blue Goose’s cockpit on either side of Hank, watching as Hank zoomed in on the chart displayed on the gizmo attached to the thing that held the steering wheel up, explaining the area just off the coastline here by the boatyard.

“The island over there? That’s Dyer Island, and on the other side is the main shipping channel that goes up to Providence, so we’ll stay on this side of the island as we head south, to keep away from that traffic.”

“Then what?” Carter asked.

“We work our way down to Newport. Bud got us a slip for the night at his club.”

“Then what?”

“We leave Newport at four-thirty Saturday morning, and once we clear Brenton Point and the reef it’s about 18 miles to Block Island. We’re going to anchor in the Great Salt Pond.”

“I thought you were going to stay at that marina bay our hotel?”

Hank sighed. “I really want to test the new windlass, so we’re going to anchor. If it doesn’t work we’ll motor over to the docks.”

“You’re coming too, aren’t you, Dad?” Huck asked.

“I paid for a room, and we have reservations on the ferry, so I guess I’m going.”

“On the ferry from Newport, right?” Huck asked.

Carter nodded.

“Right,” Hank said. “Well, there aren’t any hazards between Newport and Block Island, at least until you get close to the island. The main thing is the tides, but once we get close to the channel entrance over at the island we just have to watch the buoys.”

“And Dad,” Huck cried, “there’s a good Mexican place over there! Are you stoked, or what?”

Carter squinted his disapproval, then stepped off the Goose and walked up the pier to the house.

+++++

The 30 horsepower Yanmar started instantly; the Balmar high output alternator registered the proper voltage, 12.8, and all three lithium batteries were at 100 percent of their rated capacity. Hank grabbed his checklist and started making his rounds, checking all the seacocks on the thru-hull fittings, then proper function of the two electric bilge pumps. The bilge was dry, but he decided to check the PSS shaft seal on the propellor shaft, then the packing glands on the rudder shaft. He turned on the propane solenoid, turned on a burner on the stovetop, then shut it down before turning off the solenoid. “Huck! Turn off the propane tank, just like I showed you,” he called out.

“Got it.”

Next he checked the engine exhaust; the smoke for color and correct water flow through the coolant loop discharge. He flipped on the switches for the boat’s required lighting then walked the deck checking each light for function. A few minutes later he put away his checklist and looked at Bud and his father on the dock.

“You ready, son?” his father asked.

“As I’ll ever be,” Hank replied.

Henry and Bud slipped the boat’s lines from their cleats and handed them over, and Bud reached out with his foot and gave the Blue Goose a little shove. Hank put the transmission into forward and gave her a little throttle, and the little ship motored away from the Langston Boat Company’s docks. Daisy and Gertrude watched as he sailed away, and Gertrude was still smiling.

+++++

Carter watched his son watching him with his hands in his pockets and his stomach doing barrel rolls. He was fidgeting and picking at his fingernails as the little boat disappeared into the night…

“They’ll be alright,” Bud whispered to Carter.

“Yeah? And you know that – how?”

“Two reasons. I’ve built 90 of these, the 28, and more than 30 have circumnavigated. And next, because I have friends in the Coast Guard, and they’re going to be in the vicinity – just in case.”

“No kidding?”

Bud nodded, then he took Carter by the elbow and turned him towards the house. “Now, you look like you could use some pancakes.”

+++++

“Hank, this is the coolest thing ever…!”

Hank looked at the chartplotter and hit the Home button then the AIS overlay, then the radar, and – because it was still dark out – he wanted to monitor all the vessel traffic moving in or out the ship channel. An instant later all the information he needed was right there: the vessels moving up and down the channel, their names and home ports, their destinations and their current heading and speed. The radar confirmed their positions, and when all the information was overlaid on top of the nautical chart it was a remarkable enhancement to situational awareness, because along with all that other information he could also see bottom depths and buoys, lighthouses and other prominent landmarks used for navigation. He explained it all to Huck – who was eating it up by the spoonful and who was, so far, in love with sailing. Their elapsed trip distance was now almost three miles, and they were motoring because the windspeed was currently a blazing 1.2 knots.

“Who’s that?” Huck asked, pointing at a boat a few hundred yards behind them.

Hank checked his display and there was nothing showing up, other than a strong radar return. “They don’t have their AIS on,” he replied. He looked again and couldn’t see their running lights either and he sighed. “Oh joy. It’s the Coast Guard.”

“How do you know?”

“AIS switched off, no running lights. They’re following us.”

“Which means what?”

“We’ll probably be boarded once the sun comes up, so don’t take your harness off.” The harness, or safety harness, hooked up to a hard attachment point on the boat, meaning it was a strong connection between the wearer and the boat. If for some reason the line broke and the wearer went overboard, the harness automatically deployed a water activated life vest, and there was a small PLB, or Personal Locator Beacon, that could then be activated once in the water – signaling rescue authorities either in the region or around the world of an unfolding man overboard situation.

“What do they do when they board you?”

“Check for safety items and paperwork, unless they see something obviously wrong.”

“Like what?”

“Drugs, mainly.”

“Hank, I’ve got some pot in my duffel!”

“You…what?”

“Pot! My dad sent some with me, in case I get seasick.”

“Go below – slowly – and get it. Then bring it up and dump it overboard, but act like you’re barfing when you do it.”

Five minutes later the pot was gone and the Coast Guard boat hadn’t changed position; it was still a few hundred yards behind them, in the same shallow channel headed towards Newport. “I bet Bud asked them to keep an eye on us,” he mumbled.

“Your granddad? Why would he do that?”

Hank shrugged. “Doesn’t matter. What does matter, Huck, is that you never, ever bring drugs on anyone else’s boat. If the Coast Guard finds that stuff they can confiscate the boat, even if the owner had no idea it was onboard, and that’s that, no negotiation, no second chance. And no more boat. Got it?”

“No shit?”

“No shit. So you gotta promise me. No more, okay? None.”

“You got it, Hank.”

He switched on the autopilot then got his binoculars and swept the horizon, lingering on the patrol boat for just a second, then he nodded. The men on the patrol boat saw that and hit the throttles, then powered past the Blue Goose, apparently going on to Newport.

“Man,” Huck said, “did you see the guns on that thing?”

Hank nodded. “I think they run into a lot of bad shit out there.”

“Like what?”

Hank shrugged. “Emergencies, drug smugglers, that kind of stuff.”

“Looks like fun.”

Hank nodded. “Check ‘em out sometime. They drop by the boatyard every now and then, too. Bud always takes time to fix coffee for them.”

“Really? Why?”

“He’s in the Coast Guard Auxiliary, helps them set up training exercises, all kinds of stuff. He says without the Coast Guard his business probably wouldn’t exist.”

Huck nodded. “Yeah, I can see that.” He leaned over and looked at the display, then pointed at some numbers. “Is that how far we’ve gone, and how far it is to Newport?”

“Yup, 2.8 miles to go. You stand at the wheel, let me know if any boats come near us.”

“Gotta take a leak?”

“Systems checks, look at the bilge and the drivetrain.”

Huck nodded then stood beside the wheel, staring at the autopilot controls and the radar display. “So many things to learn,” he mumbled.

“And unlearn,” Hank said, poking his head up the companionway – before disappearing again.

Huck laughed, because he thought Hank looked like a turtle with his headed popping up and down like that.

A half hour later the Blue Goose pulled alongside the guest docks at the Newport Yacht Club, and the boys’ fathers were waiting there to take their lines. Bud was taking pictures, of course, and Hank had no doubt that the images would show up in the company newsletter next month…

+++++

They left Newport at four-forty the next morning, and the Blue Goose cleared Goat Island before sailing through the East Passage and along Aquidneck Island before reaching Long Island Sound. Hank had already programmed the route into the autopilot and all he had to do was hit ‘Engage’ and the boat made a gentle turn to starboard, to their right, then he reached inside and powered up the winch on the coachroof and hoisted the main out of the furling boom. Huck watched the sail run up the mast in awe. Then Hank set the traveler and unfurled the staysail, then the yankee, and the Blue Goose just settled into her groove and scooted along. The wind – and it was wind, not a breeze – was coming out of the northwest at 18 knots…according to the local NOAA weather radio broadcasts, anyway, but the onboard display of apparent wind was showing a solid 22 knots – with occasional gusts to 28.

And Bud knew that once the Goose cleared Point Judith, Hank’s little sailboat was going to get slammed by that wind.

And this would be Hank’s first real test of seamanship on a ship of his own. But seamanship, Bud knew, wasn’t just about skills and strength, it was also a measure of knowledge and judgment. He knew Hank, or at least he was pretty sure he did, but you never really could tell until someone was tested by the sea.

Because the sea never suffers fools. Gladly or otherwise.

+++++

The NOAA weather radio frequency on the VHF radio hooked to Bud’s belt hissed and popped, and he pulled the radio out of its holster and brought it up to his ear.

“The national weather service has issued a small craft warning for Long Island Sound, including the waters of Block Island Sound, Buzzards Bay, and Vineyard Sound. Small craft are advised against using these waterways until 1700 hours. Mariners should exercise caution if transiting these waters, and be alert for vessels in distress by monitoring VHF channel 16 and reporting any mishaps to the Coast Guard…”

“Well…damn,” Bud sighed.

“Shouldn’t we call Hank?” Carter asked, now clearly anxious.

“Hank knows what to do,” Bud sighed.

“What does that mean?”

“If he’s not comfortable he’ll turn around, and if he decides to press on…well, we’ll need to be there when they reach the dock. Won’t we, Henry?”

Henry nodded, but in truth he was a little rattled. His boy was, after all, twelve years old – and this was his first real trip on the Goose, too. “Should we go ahead and get on the ferry?”

Bud nodded. “If we need to get back in a hurry I can arrange that over there.” He took out his iPhone and called his friend at the Castle Hill Coast Guard Station and spoke for a minute of two. He hung up and smiled, then turned to Carter. “They’re doing fine. The Coast Guard patrol boat has them in sight and they report the wind isn’t real bad right now…”

+++++

“Goddamnitttofuckinghell,” Huck screamed as a 12 foot wave broke over the Goose’s bow, “what’s the wind doing now?”

“Thirty one, just had a gust hit forty.”

“Fuckme!”

Hank leaned over the transom and engaged the Hydrovane self-steering gear then set the angle on the vane. When he thought it looked good he turned off the autopilot then watched the Goose round up into the wind. He furled the main a little more and then rolled-in the staysail a foot or so; the big yankee was already furled – yet the Goose still had a lot of weather helm – so he eased the traveler a little more and watched the Hydrovane settle down, and he nodded at that. The Goose started tracking like a freight train, the Hydrovane holding her course better than the autopilot had.

He turned just in time to see Huck blowing beets into the water, then he turned away and shook his head. He really hated that smell…

+++++

The skipper of the ferry from Newport to Block Island was reluctant, to say the least, about making the trip this morning, but reluctance wasn’t in his job description. Businesses on the island depended on him to bring not only tourists but everything else, from the mail to the groceries needed to restock the local market’s shelves. Canceling wasn’t something the company did often, and it wasn’t quite bad enough out there – yet – to do that. The trouble was…he knew that in an hour or so conditions out there would get so bad that the Maydays would start jamming up the VHF, and then the Coast Guard would have its hands full with rescues the rest of the day. And besides, he didn’t need fifty seasick passengers barfing all over his boat.

+++++

The Goose was in Rhode Island Sound now, about a mile off Scarborough Hills approaching Point Judith, and Hank had his eye on the lighthouse one minute and breaking waves the next. Huck was hanging on for dear life now, clearly terrified and literally almost green with seasickness. He adjusted the Hydrovane so she steered a little more to port, then he pulled up the AIS and looked at the traffic on the far side of the point. There was rapidly shoaling water all around the point but the tide was approaching slack and the wind almost calm so close to shore.

“What did you do?” Huck asked.

“About what?”

“It seems smoother now.”

Hank nodded. I cut in a little closer to shore, keep us out of the wind a little longer. Once we clear the point that’ll change, and it’s going to get real nasty.”

“You mean…worse? Again?”

“You wanna go back?”

Huck seemed to think about that for a moment, then he shook his head. “Not unless you do.”

He saw the ferry pop up on the AIS and wondered if his father and grandfather had decided against coming…

+++++

“Where’s Carter?” Bud asked as he handed his son a cup of coffee.

Henry pointed at the rail, to Carter Ash heaving his guts into the sea.

“What a waste of good pancakes,” Bud chuckled. “Whoa! Man, he looks like the great white whale!”

“Thar she blows,” Henry said with a flourish.

+++++

Hank peered through the binoculars and was pretty sure he had the Red number 2 buoy, marking the shoals off Point Judith, in sight, so he adjusted his course again, falling further off the wind. The boat’s motion eased again and Huck moaned his approval. Hank looked at his watch and noted the time, almost ten in the morning, then he looked across at the ferry. It looked like half the passengers were hurling over the rail and he grinned.

+++++

“Damn, I haven’t seen this much garp since I was a middie,” Henry snarked.

“Gawd, I hate that smell,” a woman behind them sighed…before she too made a mad dash for the rail.

“Almost made it,” Bud said. “Well, it’ll wash out.”

+++++

Hank checked the tide for mid channel: it showed .14 kts, 76 degrees, Ebb decreasing, so the tide was almost running with the wind, but not quite. The tide was coming out of the west and the wind out of the northwest, and the confluence of forces was creating a nasty chop. The Goose had a fine entry and was cleaving the waves, but the swell was another matter. The boat was rolling now as ten foot swells came out of the west, mixing with the five foot waves coming out of the northwest, and soon even Hank was beginning to feel a little queasy.

So he concentrated on watching the horizon, then looking at the chartplotter. “Less than 7 miles now, Huck. You hanging in there?”

“Yeah. Never better.”

+++++

Carter came over and sat beside Bud. “Man, that was embarrassing,” he groaned.

“Embarrassing?” Bud said. “Hell, son, half the people on this tub are flashing hash right now. That’s nothing to be embarrassed about…”

“Oh yeah? Look at my shoes?”

Bud looked, then shook his head. “That woman standing next to you had pretty poor aim, I reckon.”

“They sell Dramamine at the snack bar,” Henry said helpfully. “They’re right next to the hot dogs.”

Carter blinked rapidly then stifled a heave – before sprinting to the rail again.

“Damn, Henry. That was just plain mean.”

“I know. Ain’t life grand?”

Someone somewhere farted and a fresh wave of stench washed over the remaining passengers; this soon caused another massive dash for the rails.

“Damn, this is fun,” Bud said as he showed Henry the can of fart spray he’d purchased online.

“You did that?” Henry whispered.

“Hell yeah.”

“Do it again…”

+++++

The VHF hissed and popped, and Hank leaned forward to tune out the noise with the squelch knob…

“Help us, someone, please help us…”

It was a girl’s voice, a little girl’s voice. He picked up the mic and keyed the microphone. “Sailing vessel Blue Goose to vessel in distress, say again?”

“Help us…my daddy fell off the boat…”

“Blue Goose, Blue Goose, this is Coast Guard Station Point Judith, are you picking up a distress call.”

“Affirmative, Coast Guard. A little girl says her father is overboard and in the water.”

“Coast Guard, roger, she must be transmitting on low power, which means they’re probably close to you.”

“Blue Goose, got it. Will check now.”

Hank picked up his binoculars and swept methodically from due south to west, then back to due south. Then from our north to west, and back. Finally…something caught his eye.

“Coast Guard, Blue Goose, I have them, compass bearing 2-6-0 from my present location, and no more than a mile out. We’re turning that way now.”

“Goose, understood, we have you on AIS but don’t show anyone else in that area.”

“Coast Guard, Goose, looks like a 24 foot center console, one outboard. White hull, light blue canvas, and I have a solid radar return on them now. Showing 2-6-3 degrees and 1500 yards.”

“Roger, Goose. We have a helicopter refueling right now. They’ll be airborne in one zero minutes, ETA your location two five minutes.”

“Goose, understood.”

Hank turned on the Yanmar and sheeted-in the staysail, then completely furled his main.

“Huck, you with me?”

“Never left, Dude.”

“Remember this?” he said, pointing to the LifeSling on the stern pulpit.

“Yup. I watched the YouTube video, too.”

“Okay, our first priority is to look for the man in the water, and I need your eyes for that, okay?”

“Got it.”

“When we see him we deploy the sling and get the line to the winch on the coachroof, then we’ll pull him in and help him up.”

“Just like a fish, right?”

“Yup. But Huck, look, you may need to go over to the other boat. Understand…?”

“You mean jump over?”

Hank shrugged. “Before you do anything, remember the most important rule out here?”

“Always keep one hand on the ship?”

“Right. Whatever you do, you hang on with one hand…to anything. You need an extra hand, ask me for help, but don’t let go of the ship. We don’t need two people in the water, okay?”

Huck nodded. “Got it.”

Hank looked at the boat, saw a little girl pointing to her left and he swung the binoculars in that direction…

“Coast Guard, Goose, I have a visual on one man in the water. Proceeding to his location.”

“Coast Guard received. Uh, Goose, would you activate the distress button on your VHF?”

“Affirmative. Activated.”

“Okay Goose, we have your lat-lon now, forwarding to the helo.”

“Hank, that dude is in fucking bad shape. He can’t even raise an arm.”

“Hypothermia. Water temp, Huck. It’s 52 degrees in there. Okay…hang on, big wave!”

A fifteen footer broke over the Goose’s bow and she fell off to port after the remains of the wave rolled under into her; Hank struggled to get her back on course and Huck came over to help.

“Thanks, shipmate,” he sighed as they got the boat pointed in the right direction again.

“Hey…no problemo, amigo.”

“You taking Spanish?”

“No way, Dude. Terminator 2!”

“Oh yeah. Hasta la vista, baby. Got it.” He had the man in constant sight now and adjusted his course to the left in order to circle around him. “Okay Huck, time to get ready. Pull the red tab on the flap there, then the sling will fall out into your hand. When he’s right by us throw the rope right in front of him…”

“Okay. Got it.”

“Okay, get ready.” Hank heard the velcro release and wiped some salt spray from his eyes, then focused on the man in the water. When he was right alongside, Huck tossed the line into the water and Hank swung the wheel hard to starboard to circle the man, then he cut power and slipped the transmission into neutral and began drifting down towards the man.

“Okay,” Huck cried, “he’s got the line!”

Hank leapt forward and got three wraps in the electric winch then began reeling the line in. “Huck! The boarding ladder! Drop it and let’s see if he can climb up!”

Huck hopped over to the folding ladder stowed over the starboard boarding gate and pulled the release; the gate dropped into the water with a loud splash.

“Huck…I need to steer right now, just keep pulling him until he reaches the gate.”

“Right. Got it, but man, this dude must weigh a ton!”

“Don’t get hung up in the rope!”

“Okay…he’s at the ladder, but Hank…he can’t do it…he’s got nothing left!”

“Okay…keep the line from fouling and I’ll try the winch again…oh crap…Huck! Hang on…big wave coming…”

+++++

“Blue Goose, Blue Goose, this is the U. S. Coast Guard. Are you receiving my transmission?”

+++++

Hank lifted his head, saw Huck in the water and the man drifting out of reach. Then he heard the Coast Guard.

“No time…” he said as he ran to the wheel and slipped the transmission into forward. He turned the boat around and went for Huck first, then he pulled the sling in, coiling the rope for another throw. Once he was on top of Huck he tossed the line and Huck grabbed it; Hank pulled him right over to the ladder and then right up on deck – in one fluid motion, then he hopped back to the wheel and powered around to the man in the water – again. Huck resumed his station, readied the line by coiling it the same way Hank had, then he tossed it over to the man again.

Hank heard a helicopter and looked up, saw a news helicopter out of New Haven hovering overhead, their cameraman leaning out over the sea – recording everything…

“Oh, swell…” Huck sighed. “If my Mom sees this she’s gonna be so pissed!”

Hank almost laughed at that, but he was still coming down from the surge of adrenaline to do much of anything yet…

+++++

When the boys walked into the Mexican place on the island everyone inside stood and cheered. Hank shook his head. Huck looked around and smiled – when a girl smiled at him. The news crew had their lights set up and a reporter was waiting for them.

“Dad? Do I have to do this?”

“No, of course not. I can handle it for you if you like.”

Hank took a deep breath, then shook his head. “No, I guess I better handle it.”

“Okay.”

“Huck? You ready to do this?” he asked.

“Fuck yeah! You know it, Dude!”

Henry led the boys over to the waiting reporter and she asked all the obvious questions, then, as she was wrapping up the segment she asked one more question. “So, what were your two doing out there today. I mean, there was a small craft warning…”

And Huck spoke right up. “Mind if I answer this one, Hank?”

“No, fire away.”

“Hank’s been teaching me how to sail, because we’re going to cross the Atlantic in June.”

“Excuse me?” the reporter asked, her mind short-circuiting as internal fuses started blowing. “You two are going to cross the Atlantic Ocean? In that tiny boat?”

“Yes indeed, Ma’am,” Huck said, grinning from ear to ear. “We sure are. Wanna join us?”

Smoke started coming out the reporters ears. “Uh, what did…just how old are you, anyway?”

“He’s old enough to know better,” Carter Ash said, taking his boy by the hand and pulling him away from the snake pit.

“C’mon, Dad!” Huck cried. “Did you see the legs on her? Bodacious tatas too, huh?!”

Hank buried his face in his hands…but suddenly the room was knocked flat by the stench of an overpowering fart.

Hank looked around for Bud or his dad, then he finally saw them laughing as they walked out the restaurant’s back door.

+++++

Judy Stone spent several hours on the used 28 the very next weekend, going over the boat with the marine surveyor she’d hired to inspect the boat. Bud remained down on the dock, talking with Emily and Hank while the surveyor went over all the ship’s systems one by one, taking notes and snapping images on his phone. The surveyor wrapped up his inspection and told her he’d have a written report to her in three days, but that the boat was in perfect shape.

“I hate to say this, but all Bud’s boats are like this. People take care of them, and I guess because Bud took care of them when they were buying the boat. They’re almost always like this, too. Just about perfect.”

“So no flaws?”

“Nope. None. The seller is asking a fair price, too.”

“Okay, so I’m good to close?”

“Yes, Ma’am, that’s what my report will say.”

“Okay. Thanks, Jim.”

Once the surveyor had left the boat Bud climbed onboard, then Emily and Hank came up.

“Well,” Bud asked. “What’s the verdict.”

“Five out of five,” Judy said, beaming. “When can we close?”

Bud smiled. “Any time is fine. When do you want me to start on the work?”

“Yesterday too soon?”

“Okay. Understood. Soon as we get the paperwork we’ll get going on her.”

Hank looked at Judy and wondered what was going through her mind. Whatever it was, he knew it wasn’t good, but it probably wouldn’t turn out good for anybody.

© 2025 adrian leverkühn | abw | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | and this is a work of fiction, plain and simple. We’ll be back soon with, I hope, the final chapter. Stay warm, and adios.

Nice one

LikeLike