An ending here, of sorts. Revisions likely when I consolidate all nine chapters into one post.

Music? Paul Simon: Hearts and Bones. Yes: Hearts. Buffalo Springfield: Expecting to Fly. Linda Ronstadt: You’re No Good. The Dream Academy: Twelve-Eight Angel. Double: The Captain of Her Heart. Dusty Springfield’s version of The Look of Love, from Casino Royale, the original 1966 motion picture soundtrack.

Part Eight

After backtracking around Keflavik, Hank set his course to skirt the small islands around Vestmannaeyjabær, and once they passed the village of Vic they faced a 350 nautical miles passage to the Faroe Islands. The weather forecasts they had downloaded looked decent, not great but decent, for the next two days – but after that there was a growing possibility of storms, this time from a tropical cyclone that had skirted the Bahamas before turning towards Bermuda. This new beast was predicted to blow itself out in the mid-Atlantic, but so far this storm had defied prediction and seemed to have a mind of its own. As for right now, there wasn’t a breath of air and both boats were motoring along at five knots. At least, Hank told himself, they were charging their batteries.

Hank had long planned on stopping in Tórshavn, then spending a week or so exploring the islands, but the plain fact of the matter was that they were running out of summer. It was already mid-August, and while it wasn’t impossible to reach Hull by the end of the month, spending a week sightseeing anywhere was looking less and less possible, and that was not what he had been hoping for. What was the point of rushing if the things you wanted to explore were lost to you? Didn’t that defeat the real purpose of a trip? Any trip?

Which had left him with the germ of an idea a few nights back, an idea that was even now rattling around in his brain.

‘What if we keep the boats in Hull for the winter, then come back next summer and retrace our path, return to the Faroes on their way north to Bergen and the fjords.

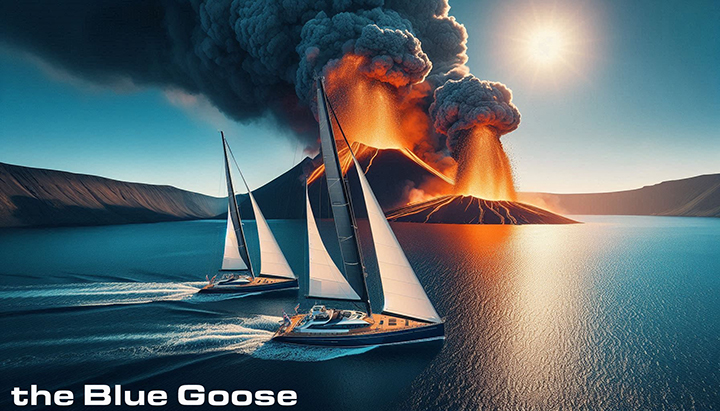

In fact, he was thinking about next summer so much that his mind wasn’t on their present situation. Grindavik was coming up on their port beam and while the shoreline was still in sight, though just barely, he saw a low, dark plume of volcanic ash streaming off the mainland straight out to sea, and the plume was maybe ten miles dead ahead. Volcanic ash, he knew, was full of all kinds of abrasive particulates, everything from silicates to larger bits of airborne pumice, but there were a gazillion different chemicals in these clouds that were toxic to breathe. The most immediate concern was damage to their eyes and lungs, and there might be carbon dioxide alerts for low lying areas, where CO2 pooled in lethal concentrations. The sea was definitely a low lying area, so would an alert apply to them?

But Judy was already two steps ahead of him when he called her on the VHF.

“I’ve just talked to one of the volcano observatories,” she began, “and they advise we head well offshore before traversing that plume.”

“How far offshore?” Hank asked, bewildered, knowing that any detour might add days to their crossing.

“Call it a hundred miles south,” she sighed. “So yes, I hear you, this is going to add at least a day to our time, but the alternative is to go around the northern coast of Iceland and that would take weeks, not days.”

Hank sighed and shook his head, but the knew she was right. He entered a new course on his chartplotter and then told Huck his plan. He hit execute on the plotter’s screen and the autopilot made the turn to starboard, then he turned on his radar and yes, sure enough, he could see the plume right there on his screen.

He nodded – because at least he could monitor their position relative to the danger…but he was fuming now. More delays…

And then he felt a shuddering thud reverberate throughout the Goose. “What the hell?” he mumbled.

Afraid he’d run into an errant shipping container he leaned over the starboard rail and found himself face to face with the grinning white countenance of an impressively large Beluga Whale. Its face was about a foot above the mirror smooth surface, and its mouth was open a few inches. The dome of its forehead was impressively huge, and the natural curve of its mouth looked inviting. Like he, or she, was indeed smiling at him.

“Well,” Hank said as he cut power and put the transmission into neutral, “hello there. How are you today?”

And to his surprise, the whale replied, our tried to, anyway. While its enunciation wasn’t perfect, it was close, and Hank grinned at the effort.

“We’re going that way,” Hank added, pointing to the south. “Where are you going?”

But then the whale shook its head – and then it swam around The Blue Goose’s stern and literally pushed the boat to a course further west.

Thee radio hissed and came alive. “Is that a Beluga?” Judy asked.

“It is, and I told him we were heading south and that seemed to bother him. He’s pushing me to the west right now.”

“Interesting. Hank, if he swam through that plume he may have gotten a lungful of pumice, and he just might be trying to warn us off.”

Hank leaned over the port rail and the Beluga was still right there, bobbing on the waves while looking up at him again. He pointed to the west and nodded: “You want me to go that way?”

The whale responded by pushing the Goose again, and yes, it pushed the Goose to the west once again.

So Hank set a course of 220 degrees and engaged the autopilot, yet the next time he looked down into the sea the whale had vanished…just like a ghost.

“Damn,” he muttered under his breath as he scanned the sea around the Goose, “now that was just weird.”

+++++

Two hours later the plume was still visible off in the distance – but it was gaining some serious altitude now. He couldn’t tell what surface conditions were like that far away, but he hadn’t seen any airliner’s contrails overhead all morning so assumed this had been a big eruption. He turned on the single-sideband radio and tuned in the BBC, and then he learned that there had been big volcanic eruptions all around the world, and that the Pacific Coast of North America had been especially hard hit just a few hours earlier. Mt. Etna, the stratovolcano on Sicily’s east coast, had just erupted, and so had Mt Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, and that volcano had long been thought extinct. There were reports of eruptions in far east Russia, but no confirmations had been received at the time of broadcast.

Hank picked up the VHF and called Judy.

“Have you listened to the BBC today?” he asked.

“No? What’s up?”

“Just tune in and listen for a while, then tell me what you think we ought to do.”

“I got it,” Huck said. “Judy’s gone down to work on it. How’re you doing over there?”

“I was doing okay until I heard this shit. Huck, volcanos are erupting all over the world, and it’s real bad on the west coast.”

“You mean like California and shit?”

“Yup.”

“Fuck.”

“Yup.”

Judy came on the air about ten minutes later and she sounded different now. Like the usual calm she projected had been ruptured. “Hank, I have no idea what we should do, but there are volcanoes all over Iceland so I think we should get away from here.”

“Agree, but where to? Keep going to Scotland?”

“There’ll be ash clouds everywhere within a few days, so our best bet is to get somewhere…well hell, Hank, I have no idea where a safe place would be.”

“I’m texting my dad. He’ll know what to do.”

“Their flight took off an hour ago,” she said. “He should be in Boston in a few hours.”

Hank didn’t like the way that sounded. If air travel was disrupted by volcanic eruptions, it seemed like the worst place you could be was in an airliner over an ocean, but now wasn’t the time to think about that. “Okay, I’m going to set a heading of 270 degrees and get away from that plume. There’s no telling how bad it is now.”

“Okay. We’ll be right behind you.”

There was a light breeze blowing now so he set the main and the genoa, then engaged the Hydrovane self-steering vane. With so much sun shining he set the angle of the solar panels to receive maximum solar gain then checked the Victron displays to see how well they were doing. He looked down, saw the surface of the sea was still sort of calm but it looked different now. Almost gritty, like there was a thin layer of gritty film spread over the surface.

And if that was volcanic grit, he thought, what would that stuff do if it got into the engine’s raw water coolant loop? Foul up the diesel? What about the Spectra water maker? Would the grit foul up the pre-filter and clog the pump? And the sails? Would grit settle onto the Dacron fabric and tear up his sails? If so, how long would it take to destroy them?

Then the thought his him.

We could be out here unable to run the engine and even unable to sail. Then what would we do?

He turned and looked over his wake and could still see Iceland back there – and that’s all it took. He swung the wheel hard over and turn back to the northwest, then he looked at Judy, now standing in the cockpit staring at him. A minute later she pulled alongside.

“I was thinking,” he began, “what would happen if we got a bunch of that ash in our engines, and then in our sails. Or the water makers. We could get halfway to nowhere real fast, then be stuck out there with no way to get anywhere…”

“Jesus,” Huck sighed.

Judy nodded. “Good call. You want to head back to Reykjavik?”

Hank nodded. “I don’t want to be out here right now. The BBC is saying nothing like this has ever happened before, so no one really knows what’s going on. It just hit me, you know? Being out here in the middle of the ocean sounds like the last place we should be.”

His phone pinged and he realized he had put the phone in its holder on the binnacle so he leaned over to look at it. He read for a second then nodded. “Text from my grandfather. They’re still at the airport, all flights grounded. He’s asking our intentions.”

Judy nodded. “Hank, we’re following you, okay?”

Hank picked up his phone and replied: “Understood. Heading back to Reykjavik now.”

A minute passed and the reply popped up. “See you at the marina. We’ve reserved your same spots.”

“Okay. Be there tonight.” He nodded then turned back to Judy. “They’re headed to the hotel and we have the same berths in the marina. I think we should motor-sail as fast as we can.”

Huck reached down and started the diesel, then turned two follow Hank as the Goose began heading northwest, back to Reykjavik. Judy got on the radio again and called. “I’m making sandwiches, so don’t get too far ahead of us!”

“Okay, take your time.” Hank said as he cycled the chartplotter to the radar screen, then set the range to 36 miles, the maximum on this unit, and the plume was still there, only now in his mind it was a dark, malevolent thing, something that could hurt him, even kill him, and then the thought hit him.

The world had just changed. Not a little, but a lot. Reality had shape-shifted and this was a new world…

Now even the air he breathed could no longer be taken for granted, then an even scarier thought hit. If it was bad here – what was it like along the Pacific Coast? How long would it take for all that ash to make it here? He remembered a couple of movies about that volcano under Yellowstone National Park, what the scientists called a ‘Super-volcano.’ In one movie more than half the country had been buried under ash, and the sun didn’t come out for a couple of years.

Would that happen now?

But why were volcanos erupting in Italy and Russia, and why were they all erupting at the same time? And then there was that extinct volcano in Africa? That just seemed beyond weird.

He turned the chartplotter back to the main chart display and noted they were coming up on the point at the southwest tip of the island, labeled Reyhkjanes on his chart, so now they had 20 miles to go to reach the lighthouse on the point, the old Garður lighthouse, where they would make the final turn into Reykjavik…

“Hank,” Judy said over the radio, “come and get it!”

“Okay, I’ll cut power, tell Huck to come alongside, make it starboard side and I’ll put the fenders out.”

“Okay, got it.”

They were only a few hundred yards off so it took just a few minutes, and she already had the cockpit table set up. She’d made Huck’s favorite, a pitcher of cherry-limeade from frozen concentrate, and then she handed up a platter of shrimp salad sandwiches and a bowl of tabouli salad.

“Wow, what a feast!” Hank said as he sat down in the cockpit. The sandwiches were on big sub rolls, and she’d sprinkled fresh dill on them so they smelled great. The tabouli was full of lemon and parsley and fat, juicy chunks of tomato oozing with summer freshness, and it all looked so good, almost like a celebration. And maybe it was. Because maybe this was the end of the trip. Maybe this would be the last meal they had out here for a while.

So he looked at Judy, and then at Huck, and he kind of choked up when he thought about that. To come so far, to get so close, and then…to end like this…?

“What are you thinking?” Judy asked.

And Hank snapped out of it and looked over at her, not really sure what to say.

“I guess this is it,” Huck said, beating him to the punch. “Our last day out here.”

Hank nodded. “Yup.”

“Let’s not jump to conclusions,” Judy said, smiling. “We don’t know what’s really going on or how bad it is out west.”

“I’ve been watching the news feed on my phone,” Huck sighed, “and it looks pretty bad to me.”

“Like what did you see?” she asked, now concerned.

“Seattle is gone. San Francisco too. Los Angeles was having big earthquakes early this morning and then the news stopped coming out of there. That sounds bad. Real bad.”

Judy nodded. “It is.” She looked up at the sky and Hank thought she looked calm, maybe too calm, given the circumstances, but sometimes that’s just the way she was. Like the worse things got, the calmer she became. He had no way of knowing, but she was worried about Liz and how she might take it if she was cut off from Henry and Hank, but that was out of her hands now. Her doctors at DHMC would have to handle all that now.

Her phone pinged and she looked at it, saw a text from Emily. She sighed then opened it.

“Are you alright?”

“Yes, WE are.”

“Where are you?”

“Returning to Iceland. How are things there?”

“Strange. People real nervous. All airline flights cancelled. Grocery store in Lebanon packed, shelves at the Co-op picked clean. No deliveries from Fed-Ex or UPS today. I went by the Langston’s house. Ellen is still there, still taking care of the kids. Elizabeth is back at DHMC, something to do with a bad liver function test. I want to talk to you. When can I call?”

“Tonight.”

“Okay. I guess you can’t talk now. Bye for now.”

“Goodbye. Take care.”

She looked up and sighed, then looked at Hank. He was looking at her, and he seemed concerned.

“Emily?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“She doing alright?”

Judy nodded. “Things are a little chaotic there. I’ll call her later.”

He nodded. “Huck, maybe you should call your mom.”

Huck nodded and went up to the bow and sat with his legs dangling over the side, and Hank looked at Judy again.

“Okay, what are you not telling me?” he asked.

Judy shrugged. “Your mom is back in the hospital, a bad blood test. She’ll be fine.”

He grimaced, looked away.

“Your grandmother is still there, Hank. She’ll know what to do.”

He nodded. “Need some help with the dishes?” he asked.

“No, I got it. You go on back, we’ll be fine here.”

Hank stood to go but she reached out and stopped him. “Could I have a hug, please?” she asked.

He looked into her eyes, saw the pain, then something else he didn’t recognize, but she was reaching out to him and he stepped into her arms and wrapped himself around her. And he found he couldn’t move, that he didn’t want to let her go, and it felt like she didn’t want him to, either. He felt her face on the side of his chest, felt the heat of her body against his own and that same strange nervous feeling he’d felt on Pegasus, when he first went to Tarawa, returned to him.

Minutes passed, or perhaps it was days or years, then she let him go and he stepped back, then turned and hopped over to the Blue Goose. She cast off his lines and pushed him off, and he went to the cockpit and turned on the engine. He looked at Huck and waved as he motored ahead of The Untold Want once again, and he was by himself – again. Judy had started the diesel and engaged the autopilot, and was clearing the cockpit table just now, Huck still up on the bow, still talking to his mom.

Still talking to his mom.

How long had it been since he’d talked to his mother…? Hank wondered.

He’d been so mad at her after Thanksgiving, when she’d invited Carter Ash and his family over, that he hadn’t wanted to talk to her – and so he hadn’t. Maybe he’d said a few words to her in passing, certainly nothing of consequence, but the odd thing, the really painful thing, was that he couldn’t remember the last time he’d told her he loved her. And then she’d gone from their lives.

Why? Why had that happened? What had happened that made him feel that way? Did anger prevent us from seeing love, the love that mattered most?

And it hit him then, in the stillness of that one crystalline moment.

Is that what love is? Does love transcend everything else, every other feeling?

Is love the most important thing we’ll ever feel?

“But…what if I can’t feel love?” he asked a passing gust of wind.

He turned and looked at Judy and he knew in his heart that he loved her. And he knew in his heart that he loved Huck, too. And Bud. And his father.

But did he love his mother?

Judy waved at him and he waved back, then he watched as she went below and Huck returned to the wheel, and he sat down and looked at the chartplotter, then over his right shoulder at that spreading plume of fouled earth spreading out over the sea, over the earth, over all of them, everything he had loved or might ever love. And he felt a thump alongside the hull again. A gentle, but insistent, thump.

And when he went to the rail he found himself face to face with the same white grinning face he’d first seen just a few short hours ago, only now the Beluga was surrounded by dozens of his kind, maybe hundreds of them. Most were swimming to the northwest, swimming away from the spreading plume, but not this one. No, he was down there looking up at him, and he wasn’t smiling now.

“Are you as sad as I am?” he asked the Beluga as he cut the throttle again.

And the Beluga just looked up at him, not sad, not grinning, just looking.

Another, smaller Beluga stopped and seemed to hover by the first one’s side, and it too looked up at him, but this one seemed intent on studying him. Another stopped and stared, then another and another and soon dozens had stopped.

And he realized what he saw on their faces, and in their eyes. It was regret. And was that pity he saw?

Or was that a reflection he saw? A reflection of his regret, the pity he saw in their eyes nothing but his own self pity?

And one by one the Belugas slipped beneath the gritty surface of the sea and disappeared. All but one, the first one.

And Hank couldn’t move now, couldn’t not stare into the Beluga’s eyes, and for how long they held each other like that he could not say, then this last Beluga slipped away, a ghost melting away inside an infinite, bottomless darkness.

“Hank!”

He shook his head, tried to break loose from the spell.

“Hank!”

It was Huck, and he wasn’t on the radio, he was calling out to him.

He turned and looked and Huck was waving frantically at him. He picked up the radio and called. “Yes, what is it?”

Huck reached for the radio’s microphone. “It’s Judy! She’s gone!”

“Gone? What do you mean, gone? Is she in the head?”

“I called out and nothing. I went down to check on her and she’s not here. Not in the head, not in the v-berth. She’s gone!”

“Were you in the cockpit the entire time? Is there anyway she could have fallen overboard?”

“No way, dude! I was right here!”

He nodded. “I’m coming over.”

Hank threw the wheel over and cut the power again, then made an S-turn to pull alongside Judy’s boat, and he tossed the fenders down again and tied off after he jumped across. Huck was frantic now, his eyes darting about, lost somewhere between guilt and helplessness and not knowing where to turn.

Hank went below and walked forward to the v-berth in the forepeak and he found a logbook from the library sitting on her pillow. And as he picked it up an envelope fell out onto the bunk.

It was addressed to him.

He closed his eyes, took a deep breath then opened the envelope.

He read through her letter twice, tears filling his eyes from time to time, until he was finished reading and could take no more, until he was sure he understood what she had told him, then he climbed up on her bunk and sat there feeling numb inside.

“Hank! What’s going on?”

He slid off her berth and went to the head then carefully opened the door, and he stood there, staring into the mirror over the sink, lost inside the infinite possibilities of her loneliness.

CODA

“Every voyage is a journey of exploration, yet each and every voyage is an exploration of yourself, of your own mind. But Hank, only open minds learn from what they find out there.”

How many times had Bud told him that? When would his words finally sink in? When would he have the courage to face the world with an open mind?

His father and grandfather were on the dock again, at the same marina, and as Hank approached the piers jutting out into the little harbor he saw them pointing at Judy’s boat when they realized Huck was alone. It was obvious, of course, that she was gone. Not so obvious was why.

But Hank still didn’t understand why.

She should have returned seconds later, moments after she left, no matter how long she stayed. And he couldn’t understand because he had simply refused to open his eyes. He had from the beginning of this voyage. He had never opened his eyes long enough to see her. As she really was, someone lost and in love.

Even though her letter to him spelled it all out. Her love not just for Henry, but for him. “Because,” she had written, “you are one and the same.” She had admitted to herself that she could never have him, just as she had come to understand that Hank’s distant relative was indeed the template, the mold into which Hank had been poured. Yet she was a physician, a psychiatrist, and when she had recognized her love she had knowingly recoiled from it, then grudgingly accepted the reality – and the impossibility – of her love. She had distanced herself from his mother after that, and to a degree even his father, because she now felt that she had violated their trust, but when the trip emerged from the recesses of his mind she had seen this voyage as an opportunity. Not to love Hank, but to understand herself. Because love had finally opened her eyes, no matter how painful the journey.

As Hank backed into the same slip again, his father hopped onboard while Bud tied off the bow line, yet Bud couldn’t take eyes off his grandson. The pain in the boy’s eyes was impossible to ignore, and Bud was – perhaps – the only person in the universe who could understand that pain.

Huck backed in next to slip next to the Blue Goose, his father jumping onboard and helping with the lines, and then the two boys just stood there, staring into the moment. At each other, for a moment or two. When the enormity of their loss became overwhelming.

Yet Bud knew. He knew as soon as the logbook disappeared from his library. He knew what the outcome would be. And still he had let his grandson undertake this voyage. Only Bud knew what Judy’s heartbreak was capable of uncovering. Because every voyage is an exploration. Of the mind. And of the soul.

+++++

“As soon as the ash settles,” Henry said to Carter, “the rains will start. Cloud cover will envelope the planet, temperatures will fall, gradually at first – then temperatures will plummet – and after that, of course, the snow will begin. It might snow for months, or it may for years, and there’s also the possibility that so much snow could trigger a new ice age.”

The boys were in their rooms; Carter Ash and Bud were with Henry in the hotel’s rooftop bar, ostensibly to watch the latest technicolor sunset. People at nearby tables were listening to Henry, because here was someone who appeared to know what was really happening. And what would happen next. And while local news stations were still on the air, satellite coverage had dropped off hours after the eruptions as the ionosphere was overwhelmed by charged particles from the ongoing disruptions and signal degradation as the upper reaches of the atmosphere filled with refractive silicates. As sources of hard news dried-up, speculation and rumor filled the vacuum; reputable authorities were scarce, and none were willing to go on the air.

“Does that mean we’re stuck here?” a plump midwesterner from Duluth, Minnesota asked Henry.

Henry turned to the man and his wife and shrugged. “Air service might not resume, perhaps not in your lifetime, so you’ll want to think about your alternatives.”

“What do you mean, our alternatives,” a woman at another table said.

“I mean, where do you want to spend the rest of your life.”

“That’s hardly fair,” the woman’s partner said.

“Life isn’t fair,” Henry said, “and this new chapter of life on Earth is going to be a lot less so. Plan accordingly, or don’t. Life doesn’t care one way or another what you do, and frankly, Ma’am, neither do I.”

“So,” Carter said, his voice now almost a whisper, “what do we do now?”

Henry nodded. “Well, we have an advantage. We have two well-found cruising sailboats. We have food and we have water. And, most importantly, we have time. A narrow window, but it’s there right now.”

“A window? What do you mean?”

“Most of the computer models for an event life this show planetary temperatures stabilizing in two to three years, and the best place to weather the storm will be in the equatorial regions. That’s the zone between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. And guess what? That includes the Caribbean, Central America, and even Cuba. Miami and the Keys are very close to that zone, too…”

“And that’s why I called my wife a few hours ago and told her to start heading to Florida,” Bud said. “On my instructions, she’s called all my employees, and they’re loading all their tools and families and heading for Miami.”

“Our objective,” Henry said, “should be to sail south to the Azores, then Bermuda and Miami.”

“Our Holding Company has land in San Juan,” Bud continued, “Puerto Rico, and last night I instructed my attorney to negotiate terms on a two hundred acre parcel in Boca Chica, and as that’s in the Dominican Republic we should have decent options going forward. Boat building is about to be a big business again.”

“You don’t mean yachts, do you?”

Bud shook his head. “Clipper ships, Carter. Much more advanced sailing vessels than we used to build but, oddly enough, for some reason I kept all the plans to all the ships our company ever built. Without such sailing ships, global commerce falls off a cliff, and if that happens…well then, civilization falls right along with it.”

“And,” Henry added, “it’s not our intention to sit back and let that happen.”

+++++

“So that’s why she named her boat The Untold Want?” Bud sighed as he read through Judy’s letter one more time. “She couldn’t tell you how she felt, and yet she wasn’t sure she’d ever find Henry again. At least not the same Henry she met the first time she went back, but then again she had you.”

“So, she went back anyway? Why, Grandpa? I just don’t understand why she went back again?”

“Because a slim chance was better than no chance at all. But Hank, step back a moment and look at the facts, will you? Well, just one fact, really.”

“What?”

“What’s the one fact that stands out to you right now?”

“That Judy’s gone. She should have reappeared moments after she left, but she didn’t.”

Bud nodded. “Correct, but what do you think that means?”

Hank shrugged. “I don’t know…”

Bud nodded sympathetically, because obviously the boy’s eyes hadn’t been opened yet. “She chose not to come back, Hank. She lived the life she found back there, and then she died. Died back there, wherever that was.”

Hank looked down at his hands crossed in his lap and he shook his head slowly. “This is a nightmare…”

“It is, yes, if you choose to look at life that way.”

“What? What other way is there?”

“She chose the life she wanted, Hank. If she’d found herself in someplace she didn’t want to be, well, all she had to do was come back to us. But that’s not what happened, is it? No…and perhaps she chose a new journey, a new way to explore, and it’s my hope she found happiness, wherever, or whenever, she found herself, and with the people she found there.”

Hank looked up at his grandfather and nodded. “Could I go back to find her?”

Bud swallowed hard, but neither did he look away. “You could, yes, but the same risk applies to you. You might arrive in a timeline without her, and then, hopefully, you’d return to us. But worse still, Hank, imagine going tomorrow. You’d still be, what? Twelve going on thirteen? The same dilemma you presented to her now would apply then, and nothing would be different but the time.”

“What if I waited until I was the same age she was?”

Bud looked his grandson in the eyes, and one thing was becoming clear. “So, you love her too?”

Hank nodded.

“You mentioned the girl you encountered at Tarawa at that news conference in St John’s. You were certain that reporter was the same girl. Why?”

Hank closed his eyes and thought back to that moment in Newfoundland. “Something about her eyes. I saw something in her eyes…”

“She’s sitting over there, you know? Her flight was canceled, too.”

Hank whipped around and looked at the woman, then, as his face turned red he turned back to his grandfather. “I’d need to go back to Tarawa. I’d have to see her again to know for sure.”

“Yes. You would.”

“Why are you looking at me like that, Bud?”

“Think about it, Hank. If that woman is indeed the same girl, then…”

“She can do it too!” he blurted loudly.

Bud looked at Linton Tomberlin who, however unlikely it may have been, seemed not to have heard Hank. Then he looked at Hank again and smiled. “Alright. Now what?”

Hank crossed his arms over his chest and furrowed his brow. “There’s nothing I can do about it now, Grandpa. The logbooks? They’re in the library, and I can’t get to them now, can I…?”

“I see.” Bud said as he looked at Hank, but then he leaned over and pulled a logbook, and just the one in question, from his briefcase. He looked at it for a moment, turning it over in the dim light, then he handed it over to his grandson. “By any chance, would this help?”

Hank did a double take then leaned over to take the book from his grandfather.

“How did you know?” Hank asked. “I mean, how could you?”

“Yes, that’s odd, isn’t it?”

“Well? Are you going to tell me?”

Bud smiled as he watched his grandson leaf through the book’s musty old pages. “Remember, this is a journey, Hank, so don’t forget to open your eyes from time to time. Take a look around, smell the roses. You’re smart, so you’ll know what to do when the time comes.”

+++++

Two small sailboats left Reykjavik a few days later, both boats sailing south, both bound for the Azores. Two sons, two fathers and a grandfather were onboard, and the Icelandic Coast Guard followed them out, then wished them a safe crossing. Strange weather patterns were taking shape and the way ahead wasn’t clear to either the sailors or the crew on the Coast Guard ship, but there was nothing to be done about it now.

Linton Tomberlin, the CBC reporter, watched the sailboats leave, while her cameraman recorded scenes that would never be watched by television viewers either in Canada – or anywhere else. She watched the boy sailing The Blue Goose, the boy who had once seemed so familiar to her, and she wondered if she would ever see him again.

© 2025 adrian leverkühn | abw | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | and this is a work of fiction, plain and simple.

Dramatis personae

The Langston Family

– Hank, aka Eldritch Henry Langston V

- Hannah, Hank’s oldest sister, from his father’s first marriage

- Jennifer, his next oldest sister, also from his father’s first marriage

- Ben Langston, Hank’s younger brother, from his father’s second marriage

- Elizabeth Langston, Henry’s current wife and mother of Hank and Ben

- Eldritch Henry Langston IV, Hank’s father

- Eldritch Henry Langston III, Hank’s grandfather

- Ellen Langston, Hank’s grandmother

- Eldritch Henry Langston, Jr., Hank’s great-grandfather, Captain of the Pegasus II

- Eldritch Henry Langston, Sr., Hank’s great-great-grandfather, Captain of Pegasus I

At the Langston Boat Company, Melville, Rhode Island

- Ben Rhodes, foreman

In Hanover, New Hampshire and Woodstock, Vermont

- Carter Ash, Elizabeth’s suitor

- Huck, or Carter Ash Jr., Carter’s son, who is not quite a year younger than Hank

In Norwich, Vermont

- Dr Emily Stone, the Langston family’s veterinarian

- Dr Judy Stone, psychiatrist, Emily’s wife and Elizabeth’s psychiatrist

In St. John’s, Newfoundland

– Linton Tomberlin, reporter for the Canadian Broadcast Corporation.

Well isn’t that interesting. Recently the WEF said that the world population needed to be reduced to 1-2 billion and they hinted that epidemics could be one way. Your volcanoes scenario has been mentioned by modern psychics as a possibility. Well it’s a number 1 year and that’s a new cycle of nine years. The seers are saying that the next 5 yrs will bring startling change to the planet. I look forward with interest to the future. Another great read. Thanks mate.

LikeLike

Recall that in the TimeShadow timeline, these volcanic eruptions are not natural phenomenon. Hints exist in the Denton Ripley trilogy at what comes next, another series of hints in The 88th Key, and more in the Beware of Darkness arc. Lots of plot lines converging now. Langston is a big player in the next arc, along with one key player barely mentioned in The Seasons of Man, Rand Alderson. Alderson and Langston are the developers of a key technology in the Niven & Pournelle series that begins with The Mote In God’s Eye, followed by The Gripping Hand, and these technologies figure prominently in Denton Ripley’s next move (which will also form the basis on TimeShadow’s conclusion).

I have an outline that simply lists other outlines. Next up, a flow chart!

LikeLike

I wait with bated breath for the next part

LikeLike