You may have already read the original from 2016, but in a way I hope not. The initial version was a “Lit Special” – ginned up with all kinds of gratuitous nonsense that was ultimately offensive, even to that audience (and that’s saying something). The bare bones of the original version remain, but the plot line of this revision is not at all what it used to be. Yes, this is a long one, too, about 130 pages, so you’ll need a boatload of tea to see it through.

And I’ve added more illustrations along the way. And just for grins, I’ve spaced out the music recommendations near the illustrations. To get the ball rolling, try Fixing a Hole, off Sgt Pepper’s.

Hope you enjoy the journey.

OutBound

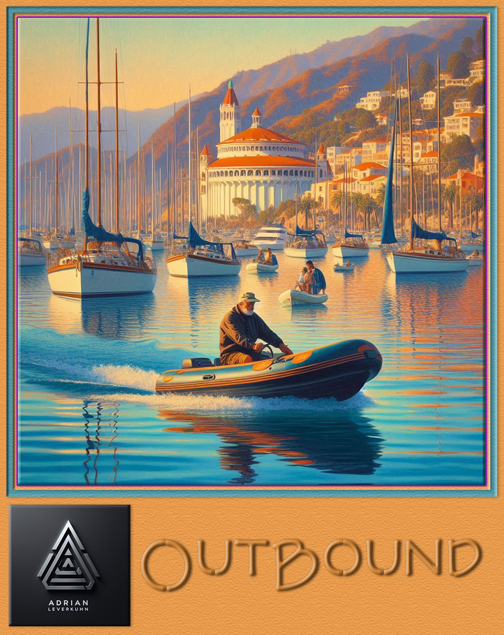

I’m sitting in my little Zodiac inflatable, the little outboard and I puttering through the mooring field off the town of Avalon, California, the little village nestled along a small beach-lined cove on the southeast side of Catalina Island. I am lost in time, perhaps because everything looks so familiar to me – yet at the same time it all feels so far away. So many things happened here, things that defined my passage through life and yes, all those things, all those people, also feel so very far away. Some mornings are made for thoughts like these. Then again, so is coffee.

The morning light is yellow, the sharply sloping beach not a hundred feet away is too, and I slip through a corrugated maze of sailboats tied to the sea, while the old casino still presides majestically over the harbor – just as it has all my life. Sometimes, in the still of night, you can almost hear the rum runners dancing to swing back in the day, when time was their time, back in the 1920s. You can close your eyes and hear their music over the wind, the waves washing along the rocky sea wall, just as it always has – and it’s a gay, inscrutable music playing against boulder strewn time. Infinite, and implacable, time – when the California we know today was little more than bungalows and orange groves.

The water below me is clear and the deepest blue I have ever known – just as it was fifty years ago, the first time I sailed across from Newport Beach to this very same mooring field. The sandy white bottom is still visible forty feet down, as relentlessly clear and full of promise this morning as it was in the 60s. Nothing appears to have changed, and even my boat looks the same. I turn and look at her reflection in the water and to my eye she hasn’t changed a bit – at least not as much as I have. Troubadour is an Alajuela 38, and I bought her new from Don and Betty Chapman in Newport Beach now more than 50 years ago, and yes, she’s seen a few miles under her keel. So have I, come to think of it. Yet I think it fair to say she’s been in good hands all that time – even if they were mine.

And I’ve been looking at my hands a lot recently, perhaps more than I should. Right now, lost in time as I putter through the mooring field off Avalon, I can see my hands have changed a lot. And though I hate to admit there are days I hardly recognize them, this is a truth so basic it cannot be refuted. Still, when these moments catch up to me I have to stop and wonder, wonder what happened to these hands, and to me, because Troubadour looks the same. Why did I have to be the one to end up with these hands? Time doesn’t seem fair, but when has time ever been so.

I remember looking at my grandfather’s hands once and wondering what all those brown spots were, those blotchy things on top of his hands. Why were his fingernails kind of yellow and ridged. And the funniest thing about those hands, and his arms, too? He had little scars all over them, and most were from cuts he’d sewn up himself. He told me many times how he’d just dipped a needle and thread in whiskey and then sew himself up, and he’d never thought anything of it. It was what you did to stop the bleeding, so you did it and moved on to the next chore, which was what he did – more or less – all his life. Maybe I was simply following in his footsteps. Now, looking at my hand on the outboard motor’s tiller I recognized these hands for what they were. They were my hands now, yet in a way they were my grandfather’s, too, right down to the yellow ridges. I am an echo, I am his echo. I always thought I was just me, but now it’s easy to see how absurd that is. And how time has made it so.

I remember me and Pops sat and watched The Petrified Forest one time, that movie with Leslie Howard and Bette Davis – and some kid named Bogart – and when the movie was over he told me about his own trip west in 1919, just after the war. How there hadn’t been highways crossing the United States back then, and more often than not there weren’t even well defined roads. He had a car, and God knows how he had afforded the thing, but he and my grandmother made the trip out west together – from Brooklyn to Los Angeles. A few cities had paved streets – paved with brick, he told me – but by and large the roads that connected cities were primitive things, often little more than sandy tracks winding through wheat fields and scrub-filled forests and, yes, deserts too – just like the barren landscapes we’d seen in The Petrified Forest. With the hard, narrow tires that cars had in those days the wheels settled down in the soft sand, often so deep that drive shafts were worn down by the sand, and he’d had to replace two solid steel shafts between El Paso and Flagstaff. Just polished down to nothing, worn down by miles and miles of time. Took them more than a month to make the trip, and he admitted to me that night, once the movie was over, that they should have taken the train and bought a car once they settled down in LA, but that wasn’t my grandfather’s idea of life. He wanted to get out there in the world, smell the road, meet people along the way and have some fun – and maybe get in trouble too, because that’s what his life was all about. I guess he passed that on to me, for better or worse, because in the end I bought Troubadour and never stopped sailing to those sandy, out of the way places.

I didn’t plan things that way. Things more or less just kind of happened. The way life always happens. Unexpected things, like the kind of people you never thought you’d run into, not in a million years. Doing things you’d never thought you wanted to do, going places that held no interest to you – until you got there and started to taste a little of that life for yourself.

Life for me, at least my life before Troubadour, had been like the first thirty seconds of a roller coaster, the part where the ratcheting chain hauls you up the first huge incline. I was in the lead car right about then, too, looking out at the world during that little pause at the top, just before the car takes off down that first steep drop. There is, I seem to recall, this flash of anticipation up there, then a little fluttering exhilaration in your gut as you slowly roll forward – followed by the dawning realization that life might be far more interesting somewhere other than on this roller coaster. Maybe I never felt that way, not in that moment before the fall, but about half way through my ride I began to develop an appreciation for smooth bicycles on warm country lanes. Funny thing, though. That was my fault, not the roller-coaster’s. But isn’t life always that way?

Which, I think, makes Troubadour all the more ironic. Troubadour was my very own nonstop roller coaster ride, yet she’s my oldest friend now. I know her aches and pains and her ups and downs as well as I know my own – yet to a few people I know that’s what makes her such an off-putting idea; she’s not flesh and blood so what am I talking about? She’s just a boat, these voices say, and how can some inanimate thing become your friend?

But that’s not the right question, and I think they’ve missed something important. After so many years and miles together, my life with Troubadour became a reflection of my life. Motoring through this mooring field or listening to the music of life through the night in her cockpit, when I think of Troubadour I end up looking down a hall of mirrors at an endless series of reflections, but here’s the thing, the most important thing. What the journey leaves with you, in the end, is so much more than the effort required to make the journey. If you’ve done it right, if you’ve lived your life on your terms and taken care of her as she took care of you – when the wind was howling and the seas were crashing down all around you, when you look into that hall of mirrors you’re going to find that there was a whole lot more to the relationship than those other people will never know. Words like respect and trust come to mind but are as easily discarded. So too is a word like love. Maybe, just maybe, when you measure the span of time within an echo you might begin to understand where I’m coming from, but that word is respect.

Or, maybe not. It kinda depends on how truthful you are with yourself.

+++++

I started playing the piano in kindergarten, maybe a little before, but who knows, really; things are a little vague on that part of the score. I was pretty good too, or so I was told, at least for a five year old. My piano teacher, a grand old woman who kept a grand old Steinway in her grand old music room seemed to think I had a grand talent, but here’s the thing: I was always more interested in composing music than in playing. And not to make too big a deal of it, but from the beginning I hated performing in front of people. I could say that I hated the experience but that’s not quite true. I was terrified.

Imagine you’re the only person standing on a stage. There’s a spotlight on you, and only you, and an endless sea of upturned faces awaits your every mistake, and every one of those faces is staring at you. But you’re naked, as naked as the day you were born. And about the time you realize you are standing there in all your naked glory, someone in that sea of faces starts to laugh. Then another nameless face starts to laugh, and pretty soon everyone is laughing – at you.

Some people call this a social anxiety disorder. Okay, slap a label on it if it makes you feel better about yourself, but it is what it is. Whatever it is. You have never seen the flop-sweats like mine. Take my word for it.

So my first recital was a sodden disaster, and that set the stage for many more disasters over the next few years, and yet I think, in the odd way anxiety splits like light through a prism, these first reactions to my first trembling moments paved my way very own Yellow Brick Road to Troubadour. I felt okay playing one on one, or even with one or two people looking over my shoulder, but if you dared put me in a venue with hundreds of people looking on, well, I simply came undone. I just couldn’t play, froze up like an ice cube and that was that – if you know what I mean. And it wasn’t stage fright…no, it was more like stage catatonia. I got over it once, for a while, anyway, but you know how such things go. The feeling comes back when you least expect it, and the experience ain’t pleasant when your turn comes ‘round again, no matter how many times you’ve felt naked and exposed.

Anyway, some time in junior high a bunch of really hip kids decided to form a band. Mind you, these guys were like twelve years old and had never played an instrument in their lives, but two of them got electric guitars for the holidays and started banging out the simple progressions of Louie-Louie, and my best friend got a massive Ludwig drum set – because that’s what Ringo played, in case you didn’t know – and they needed someone who could play bass. Well, I could. I was playing both the acoustic bass and guitar by that point, and my grandfather had a massive pipe organ in his house that I’d been playing for years, so I had that one under my belt too. You know, the kind you play with your hands and your feet.

Again, some people said I had a talent.

At any rate, the hip kids convinced me to join their hip new group and I guess you could truthfully say that I taught them how to play their hip new instruments over the next year. One of the kids, my best bud Pete Davis, was a soulful twelve year old who liked writing poetry and was already decent on the drums, and we started putting music to the words spilling out of his head. Anyway, he’d share his musings with me and somehow real music started to take shape out of that hopeless teenaged morass.

Hey, you never know, right?

I looked back on those first compositions of ours as a thick slice of life, the wonder of coming of age condensed into two and a half minutes of pre-pubescent wailings about acne, nocturnal emissions, and the pure, unadulterated lust that only thirteen year old boys have for the complete unknown, i.e., girls. We were at that age when sex becomes the center of the universe, in other words we were barely functioning morons, a time when sitting next to a girl in class, and I mean any girl, was pure torture. We knew we wanted to do something with them but I’m not sure any of us knew what the hell that meant. A quick, sidelong glance at crossed legs brought on waves of pure hormonally driven angst, a curious feeling given that this headlong rush into the netherworlds of the limbic system was defined by outright ignorance.

But here’s the thing, the one big thing. We were pegged to play at our school’s Big Spring Dance the last weekend of our last year in junior high. We had a couple of our own pieces to play but by and large we were set to grind out rough approximations of a bunch of Beatles and Stones songs, with me doing double duty on bass and keyboards.

I was, of course, terrified, and it is at this point in the tale I need to tell you about my grandmother. Her name was Terry McKay, and she was about ten or so years older than I was at the time. She was Pops’, my grandfather’s, third wife. The first two died on him, but that’s neither here nor there. Pops was a movie producer, and kind of a big deal in Hollywood, and Terry was, well, ‘about’ half his age. But let’s get this out in the open right now: I had this thing for my grandmother. She was an actress, by the way, and Life Magazine had called her The Most Beautiful Woman in the World in the year of our Lord 1963. So did I, in ‘63. Whenever she walked into my room at home I damn near had a heart attack. Yes, I had it bad. Sitting in a classroom full of crossed legs wasn’t even in it with what Terry McKay did to yours truly.

Anyway, I was talking to Pops and Terry about my stage fright one night before the Big Spring Dance and Terry told me she had been overrun by anxiety as a kid, even when she was on movie sets and sound stages, and it still happened just about every time she had to get out there and do a scene. Oh yeah, Terry was from London and had grown-up on the stage, and as the Beatles and the Stones were all the rage at the time, that whole British vibe had rubbed off on her. So, a few days before The Big Spring Dance, Terry worked with me, showed me a few tricks to make the terror a little more manageable. Some of these worked better than others, but c’est la vie. The fact of the matter was simpler than that: Terry was directing all her attention at me and I loved every minute of it.

So, not only were there several hundred people at The Big Spring Dance, I knew each and every one of them, too. I had probably chewed my fingernails down to stumps by the time we were set to take the hastily erected stage at one end of the boy’s basketball court, and I found that the only way I could function was to literally turn my back to the dance floor – so I did just that. For almost two hours we rocked and rolled and I had not have the slightest idea if anyone else was out there or not, and when it was finally all over I packed my stuff and ran out to Pop’s car – and vowed to one and all that I’d never do anything as stupid as that ever again.

We were, of course, and as a direct result of the strength of our performance at the BSD, invited to participate in a local ‘battle of the bands’ contest to be held in early July in Westwood, and we needed two songs of our own in order to be contestants. That being the case, we turned Pete’s lyrics and my first ‘rock’ composition into something really special – for thirteen year olds, anyway, and then I cobbled together something generic and altogether bland for our second entry. We practiced and practiced until we were blue in the face – then it was time to set up our instruments on what was indeed a Really BIG Stage on a grassy quad by the practice field at UCLA.

“How many people are out there?” I anxiously asked one of the promoters as Pete set up his drums.

“Oh, last year we had about two thousand, but we’ve sold five thousand tickets so far…”

My knees were knocking by the time they announced us, but once again I turned the organ so I faced away from the upturned faces and as such we launched into Pete’s soliloquy – a soothing, polished love song that just sounded silly when five by then fourteen year olds belted it out, but the girls out there loved it and they started getting into it.

Then we slipped right into ‘Lucy-Goosey’ – my hastily contrived fluff piece, and that brought the house down. We won, too. The contest, and we picked up a recording contract – with Lucy on the A side and Pete’s soliloquy on the flip side. The 45 sold a half million copies before we were in high school and as I was the songwriter listed on Lucy the lions share of the money went to me.

And that was the end of that, of course. Lots of bitter vibes because of money. Always. Yet Pete and I stayed together, he always stuck with me through thick or thin, and I never turned my back on him, either.

I haven’t mentioned my parents because, well, they died when I was young, like three years young. An airplane crash, a jetliner taking off from Mexico City, and really, I haven’t any memory of them, though I had a photograph of them on my dresser. I lived with my father’s father and his second wife, and I grew up in Beverly Hills. Then she died, and I don’t want to make too big a deal about it, but death was kind of defining my reality by that time. Things didn’t last, people died – and that was that. My parents were both show business types, too; Dad was a director and Mom was an actress of some repute, and I don’t know how to say this other than I grew up around Hollywood types, lots of famous people were always around the dinner table, so between my parents and grandparents my upbringing left me with, well, let’s just call it a different sense of proportion. If people saw glamorous stars and western heroes, I saw sullen, moody drunks sitting by the pool out back – most always fawning over Terry’s legs. I mention this only to add context to the sudden fame thrust on me after Lucy-Goosey went platinum, just as Pete and I showed up for class at Beverly Hills High. I also mention Terry’s legs because they truly were the most fantastic things on God’s Green Earth, and take it from someone who knows because it’s a bitch lusting after your grandmother.

I had, for my part, decided to concentrate on classical compositions after the band fell apart, which pissed a whole lot of people off, but I kept at it all through high school and into college, yet by that time what little fame Lucy generated had all but slipped away – and I was grateful, too, because by the time I went off to college I considered the piece pure garbage.

If I forget to mention it later, all musicians hate their own stuff. And the more they hate it the better it sells. Go figure.

The Beach Boys \\ Surf’s Up

So, anyway, I went to Stanford unencumbered by all that fame baggage, and I studied composition and philosophy with no job in mind – until a friend of a friend asked me to join a group being put together up in Berkeley. Once it became more widely known among those people that I had, once upon a time, penned Lucy-Goosey, well, they really-really wanted me to join their little group.

“I always wondered what happened to you,” Deni Dalton said, and that’s how we met, Deni and I. She had this smokey voice that seemed to seethe dark sexuality, and when she looked me in the eye I felt like a banana being peeled in the monkey house. Whatever protective layers I had on that day, say that look of smug condescension I liked to put on from time to time, she cut through that shit with a hot scalpel.

Deni was Music wrapped in pure Sin. She was bigger than life. I was in love with her within minutes, but then again everyone who laid eyes on her fell in love with her. She always wore black, too, back in those early days. Black hair and black mascara, just call it heavy black makeup, even her lipstick – so she was pure Goth long before there was such a thing. If you remember the old Adamms Family show, the one with Carolyn Jones as Morticia, Deni projected that kind of vibe. Just add a guillotine and a microphone and you’ve got the complete picture.

But she had kind of a black heart, too, and I think that’s fair to say even now. Mercenary, some might’ve called her. Not exactly educated yet street smart, she came from a very poor family and she read people like professors read books, and maybe because of her upbringing that’s why she had a thing for money. She was always looking for the next angle that would lead to fame and fortune, and I think after she took one look at me she saw an irresistible opening. Turns out she knew more about me than I did, or maybe she thought she did. I was never really sure.

“Your Dad still with Universal?” she asked. Ah-ha…

“My father died when I was three.”

“Aaron Dorskin? He’s not your father?”

“My grandfather.”

“Oh, right. He’s still with Universal, isn’t he?”

“Last I heard.”

“Well, we’re looking for someone on keys, and Luke says we should give a listen. So, I’m listening.”

We were in the living room of this run down three story house in Berkeley, and all there was in the room, besides a dozen or so stoned-out people on a u-shaped, purple velvet sofa, was an old upright piano – and then, wouldn’t you just know it, one of the girls on the sofa went down on the guy sitting next to her.

So…I looked at this chick for a moment and started playing to her rhythm, then Deni caught where I was going and she stood and started swaying to the music coming from the other girl’s mouth. I was drifting between Bartok and Dave Evans until this chick hit the short strokes, then I just let the music flow for a while, a loose, swirling flow, and when everyone was finished Deni came to me and kissed me for the longest time. But that was Deni. When she felt like sex was the key to open the way, she played every note she knew.

And so began a very interesting period of my life. I like to think of it as my purple-paisley-patchouli-period, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Sorry. That happens a lot.

+++++

It was a funky house, of that much I was certain. If the Channing Way neighborhood was kind of like the Manhattan Project of seismic music going down in Berkeley, then maybe Deni’s purple paisley house was ground zero. Her background was coffee house blues-folk, kind of a dark California counterpoint to Paul Simon’s more upbeat New York vibe, and you might get that if irony is your thing. And if Simon had inherited a little bit of Gershwin, Deni had been mainlining Thelonius Monk for years – yet I came along when she felt she was ready for fatter, more complicated sounds. She wanted to create fat, epochal rock anthems for a new generation growing tired of Beatlemania. She didn’t want cool reflecting pools, she wanted steamrollers and wrecking balls. Most of all, she didn’t want to play small clubs anymore. She wanted to hit college campuses and then, maybe, if she got lucky, move on to bigger and better things, but she saw rock and roll as a doorway, an entry into something really big and bold.

To me, as a keyboardist in 1968, big and bold – and fat – meant Moog synthesizers and mellotrons. Yes, fat is a term – usually associated these days with Keith Emerson and the big, beefy synthesizer sounds he poured into the closing bars of ELPs Lucky Man. Those two instruments, I figured, might allow some of the more bombastic elements of classical elements to merge with the relatively simplistic progressions of rock – and like every other young, classically trained musician on the planet, I knew Sgt. Peppers had shown us the way move on, while Pet Sounds and Jim Morrison had given us the tools to break on through to the other side. George Martin and the Beatles began introducing classical motifs on Sgt. Peppers, but it was their Fixing A Hole that caught fire in Deni’s mind. The Beatles married the baroque and old English choral music and it was brilliant, but it wasn’t American. The Beatles were a Jaguar XK-E: think of something restrained and elegant, gorgeous yet full of barely restrained potential; what Deni wanted was a Shelby Cobra with glowing pipes, something untamed and unleashed, music that would overpower the soul and make people scream. In essence, she wanted to take people where raw elation overpowers sensibility, to that place in the mind that easily succumbs to unfettered emotional power.

Deni had some ‘cred in the music business, credibility that had probably grown out of her street smarts, but she didn’t have real credibility where it counted. Not the kind I had, anyway – because what I did have was Pops, my grandfather, and I had Lucy-Goosey. Pops was fairly high up on the food chain at Universal, and their MCA Records division wanted to cash in on the exploding pop/rock market that Capitol had cornered. So, we retreated into the house on Channing Way in February ‘69 and didn’t come out again until May, and only then did three of us hop in someone’s old VW Microbus and slither down the 101 to Burbank – and we went straight to Pop’s office.

He was old by then, but he was also sharp as a tack and still had good instincts. We walked in and he looked at us like we’d just crawled out from under a rock, which, I have to say, wasn’t too far from the truth.

“Aaron,” he asked when he quasi-recognized me, “is that you under all that hair?”

You see, by 1969 my hair was hanging down somewhere around my waistline, and George Harrison’s beard had nothing on mine. Well, his was probably cleaner.

“Hey, Pops,” I said, ‘Pops’ being my characteristic greeting. “We need a recording studio. I want to cut an album.”

I am not, you understand, one to waste time on idle chit-chat.

“Oh?” he said, with one raised eyebrow. One eyebrow meant he was listening. Two meant you needed to start running for the exits.

So I tossed our boxed demo reel on his desk, a big Tascam reel-to-reel spool, and he looked at it, then at Deni. And you have to understand this about Pops: he was only interested in her tits at this point in the process. If she could sing, great, but she had great tits and I could see that working over in his mind – as in: she’ll look great on an album cover. He had no interest in her physically, only in the commercial appeal of her tits.

Like I said. Instincts. Great instincts.

So he picked up his phone and dialed an extension.

“Lew? Aaron’s here, and he has a demo. Can I send him over to you right now?”

So off we went, off to see the wizard. A dozen people gathered and listened to our demo and we walked out an hour later with a recording contract. We hopped in the VW and drove back up the 101 in a blinding rainstorm, got back to the purple paisley house a little after midnight – and Deni attacked me then. In a good way, if you know what I mean. We came up for air a few days later, and the really interesting thing about that torrid affair was that we finally realized we were like heroin to each other. We were dangerously intoxicated when we mixed, so much so we knew we were in real danger of losing ourselves, each inside the other. We stepped back after those two days, afraid we’d found the key to spontaneous human combustion.

Yet after those two days and nights wrapped up, Deni dropped the whole Black Goth thing and went in for the deep purple paisley look then rocking the East Bay scene. Flowing silk capes of purple, and then the house began to reek of patchouli. Patchouli incense was burning 24/7, and she put patchouli oil on everything, notably the polish she used to wipe down her rosewood furniture. The scent wasn’t quite overpowering but it came close, and the whole patchouli thing became indelibly linked to those months. I can’t not think of her when I run across that scent.

Anyway, by that time Pete had transferred from UCLA to Berkeley and suddenly we had two percussionists, but hey man, that’s cool. We loaded up all our gear and ambled back down the 101 to Burbank a week later, and we had several days booked to get the sound we wanted down on tape. I’ve since read books on musicians of that era, these being little more than monographs of artistic egoism run amok, and I shudder to think what would have happened to us if that had been the case. Instead, it seemed as if Deni and her mates knew this was their one big shot, and they had to get the job done this time or prepare to wait tables for the rest of their lives. In the end we came together, Pete and I and her friends, and the results were something else. We called ourselves Elektric Karma.

Slick, huh? The ‘k’ in Elektric was all Deni, and pure Deni.

We ended up spending a month in the studio, yet before we were finished MCA released a single that shot up the charts into the top-10, and on the strength of that alone they booked us to play three nights at the Universal Amphitheater later that summer – and I didn’t think anything about my anxiety issues at the time, maybe because I was so wrapped up in the moment.

Deni was the lyricist now, and she was a good one too, but she wasn’t quite what I’d have called an original. She listened to other recording artists all the time, listening for inspiration and ideas, but she was a natural born plagiarist – always looking for a new way to spin an old phrase, or slightly altered transitions between sections of a song – yet she couldn’t read or write music, what you call notation. She had good instincts, an intuitive grasp of the inherent order within a musical phrase, but she couldn’t see structure when expressed in notes and chords on a piece of paper. This wasn’t a big deal as I looked at the innate phrasing of her lyrical constructs and went from there, and as she wrote new stuff she’d come over to me and sing variations as I tried to parse her phrasing. Not a big deal, and most pop music was and has been created that way, yet it was a big move away from the classical paradigm – where arias are derived from the inherent structure within a specific passage of supporting music.

An unknown named Elton John showed up while we were in the studio and he listened for a while before he disappeared, and I dropped by one of his sessions a few days later and was blown away by the exuberance of his showmanship – even in the studio. And it hit me then, my ‘lump on a log’ stage presence was not a good thing at this level. And I knew I was not and would never be an Elton John. He was an impressionist masterpiece and I was an old Dutch still life – destined to reside on the edge of the stage, the edge of the world, my back always turned to the action – and I knew there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. As soon as the lights on the stage went up I began to freeze inside, like my mind had suddenly and completely been encased in brittle ice.

So, our album was released and it was a bigger hit than even Pops thought it would be. And yes, there was lots of cleavage on the front cover. Purple paisley and cleavage. My God, Deni did have canyons of cleavage. We played a few small gigs around Sunset and Hollywood, a few parties in the Hills of Beverly too, and we started mapping out our second album during that time. Then our first night at the Amphitheater came up and everything inside me just kind of snapped. I couldn’t even walk out on stage for our practice session that afternoon, and for the first time what had been kind of a modest idiosyncrasy turned into a real liability. I looked at my mates looking at me and I knew they couldn’t understand…hell, I didn’t understand…but this was something that could seriously fuck up their chances of making it.

Pops called a doc, some Beverly Hills shrink, and she came out and gave me a shot in the hip, told me to rest for a half hour, and she sat with me and we talked about the roots of my anxiety. About my parent’s death, my fear of being abandoned, everything I could think of in an hour and a half.

She looked like Faye Dunaway, if you know who I mean. About fifty, blond hair and seriously gorgeous. Smart? Dear God. It was like she had this ability to look inside souls, take an inventory and figure out what was wrong. Me? Sure, it was all about losing my parents when I was a kid, that was obvious. My dad was an actor and he had gone down to Mexico, to Acapulco, to receive some kind of award, and their plane crashed on the way back, so yeah, separation anxiety lead to more and more anxieties and Pops never had any idea. Hell, neither did I.

But Terry did.

She’d had me pegged since the first time I froze on stage for a piano recital. She knew from bitter experience.

America \\ Keith Emerson and The Nice

Anyway, understanding did not lead to catharsis and by the time we were called on stage I was no better. The doc’s magic potion helped, but Terry was there and just seeing her helped me keep it together long enough to do the show, and while it was magic, the ovations and the wild applause were like a new drug, but as I walked offstage I passed out. Down like a sack of potatoes, right on the edge of the stage.

Or so I read in newspaper accounts the next morning. Despite not having diabetes the episode was ascribed to hypoglycemia and that was that. I spent all that next day working with a studio musician who would be on standby, a kind of understudy, in case I cratered that night – and of course I did.

I watched from backstage as this stranger played my music, and in fact he played better than I had, a subtle fact not lost on Deni and her bandmates. I didn’t even show up for the third night’s performance, and when we returned to Berkeley the next day everyone tried not to make a big deal of it – but I knew something had changed between us. We all did, Deni most of all. I felt like damaged goods, a broken doll that not even all the king’s men could put back together, but we started writing music and pretty soon all was forgotten – if not forgiven.

I leaned a lot on Pete in those days, of course. He’d been with me since middle school and he knew the score. I can’t overstate this, because there were rumblings about ditching me after we returned to Berkeley, but Pete kept everyone in line. He was my behind the scenes advocate, and the best friend I ever had.

We went back to Burbank a few months later and had started laying down tracks when word came that we were going to tour North America in the fall and Europe the coming winter – and I started going to that shrink in Beverly Hills more often. Maybe she could help, or so I told my mates.

‘Yeah, maybe,’ they said.

Then a funny thing happened. The shrink invited me to go sailing with some friends of hers one weekend. I accepted the invitation, too, if only because I wanted to get to know her better, and I ran out and got a haircut too. Bought some boat shoes, of all things, and some natty red sailing shorts to go with them. Oh, I looked so Beverly Hills in my Polo shirt and Ray-Ban aviators. So not me.

The boat, a huge racing yacht that had been famous in the 30s, belonged to her husband, a billionaire property developer who apparently owned half of LA, and they had a professional crew sailing the boat so all I had to do was sit around and look interested in my boat shoes. Yet the truth of the matter was I did indeed find sailing interesting. In fact, the idea of sailing away from all my anxiety seemed enticing, more so by the minute. I talked to the skipper about boats and sailing for a while and I learned a lot that afternoon.

There was another couple on the boat that day, a property developer from Newport Beach who had brought along his wife and daughter. The girl looked a little younger than I, and she had been studying some kind of psychology at UoP up in Stockton. And hey, she loved our single. Her name was, of course, Jennifer – because every other girl in OC was named Jennifer, and probably had been since the beginning of time.

She looked like one of Southern California’s very own home grown Hitler Youth so common to Orange County back in the day: rich, privileged, blond haired and blue eyed, yet she was sweet in a troubled kind of way – and she loved sailing. Well, I thought I might love sailing too so we had something in common, right? Anyway, we talked boats and I figured out pretty quick she knew a lot more about boats than I ever would. She’d grown up around boats and knew the lingo, which was cool. And while that was nice, she also really, really liked the first single off our album. She even had an original 45 of Lucy-Goosey, bless her heart, and we went out for a burger after we got back to the marina, then I drove her down to Newport, to her parent’s place on Little Balboa Island, but when we got to the 55 she pointed me towards the beach and we went down to the Peninsula instead. We talked through the night, watched the moon disappear just before the sun decided to show up for a return engagement. She was sweet and I got into her way of talking real fast, thought it was kind of cool.

There was a boat show in Newport, she told me, usually in April or May, and she wanted to know if I’d come down and go to it with her. I said ‘sure, sounds fun’ before I knew what had happened, and we looked at one another when I dropped her off at her house like we were not quite sure where this was going. I wanted to kiss her, and I could tell she wanted me to, but I couldn’t – because I was afraid, of course, and I told her so, too. I told her about seeing the shrink, about my looming performance anxiety and she seemed to understand. Anyway, I gave her my number at Pop’s house and she leaned over and kissed me once, gently, then again, not so gently, and then she told me I didn’t have anything to worry about where she was concerned and everything kind of slipped into place after that. Right there in the car, as a matter of fact.

We finished the second album over the next few weeks then took a break, our first big tour not scheduled to begin for a month, and I went to Pop’s house to unwind. Everything seemed pretty much the same, except Pops seemed to be slowing down, and suddenly, too. He said his back hurt more than usual, that the pain had worsened recently, and Terry and I talked him into going to see his doc.

And Jennifer called that night, said she was going to be at the marina Saturday and wanted to know if I wanted to go out on a new boat. Sure, I said, and we set a time to meet up – and after that I couldn’t think about anything other than her – until my next appointment with the shrink, anyway. Pop’s internist was in the same building as my shrink so I dropped him off for his appointment then ducked in for mine, but when I came back for him an hour later he was still inside – so I sat and waited.

And waited.

And a nurse finally came out and asked for me, led me back to some sacrosanct inner cave – where I found Pops all red-eyed, an old internist handing him tissues. Prostate cancer, advanced well into the spine was the preliminary diagnosis, but biopsies would be done early Monday morning and we’d go from there. We left and he was pissed off because the same doc had told him a year ago the pain was probably related to a fall he’d taken a few years before. Maybe if the doc had been more thorough he might’ve had a chance now, because if the cancer had moved into the spine that was it.

“What do you mean, that’s it?”

I understand my parents died when I was three, but since then no one I knew had kicked the bucket – and now, all of a sudden, the most important person in my life was telling me he could die, and soon? That this was it? The ride was over?

I had an emotional disconnect, I guess you might say. I was a little more concerned with my own well being than his in that moment, a little more than afraid – for me and my future. No, let me rephrase that. I fell apart and we held on to one another there in the lobby for a long time, then we walked over to Nate ‘n Al’s for bagels and lox. He called some of his buddies from the studio, told them to come over for a few hands of poker that night – which was code for ‘the shit has hit the fan,’ and then we sat there watching the ice melt in our glasses of iced tea, neither of us knowing what the hell to say to one another. Terry would surely come apart at the seams tonight, he said, then this lanky gentleman walked in and came over to our booth and sat down next to me.

Jimmy Stewart, in town between shoots and an old friend of the family, looked at Pops and sighed. “Aaron, you look awful. Now tell-tell me, why-why-why the long face?”

So Pops lays it out there and then Jimmy is all upset, the ice in our iced tea is melting along with our world, then Stewart finally turns and looks at me.

“Heard that album of yours. It sure isn’t Benny Goodman, is it?” he said with his trademark chuckle.

Pops broke out laughing at that. “It sure isn’t, but that lead singer of theirs sure has great gonzagas. World class, if you know what I mean.”

Stewart rolled his eyes, shook his head. “All he can think about at a time like this is tits. Aaron? You’ll never change.”

“Amen to that, brother,” Pops said. “What do you have in that sack, James? Another model airplane?”

“Yup, yup. Me ‘n Hank, you know how that goes?” Hank being Henry Fonda, in case you were wondering.

“Did you ever see his model room, Aaron?” Pops asked me.

“Yessir, been a few years, but…”

“I was building that B-52 when you were up there, wasn’t I?” Jimmy recalled. “Wingspan this big,” he said, holding his hands about a mile apart, and we all laughed. He got up and patted Pops on the shoulder, told him he’d call soon, then he ambled over to a table where Gloria was already waiting and I could see the expression on her face when he told her. Small town, Beverly Hills. Good people, too.

I got up early and drove down to the marina, met Jennifer at the anointed hour and she took me down to a slip below an apartment building and hopped aboard a brand new Swan 4o. There were two other girls onboard already and they slipped the lines, let Jennifer back the boat out of the slip while they readied sail. We motored out of the marina after that, then raised sail as we turned south for Palos Verdes – but with barely enough wind to fill the sails the girls soon gave up and turned the engine on again. Seems they were delivering the boat from the marina to it’s new owner down at the LA Yacht Club and I was along for the ride, but by the time we cleared the Point Vicente lighthouse we had enough wind to raise sail again and had a rip-roaring nine mile sleigh ride after that. Feeling the motion, the wind through my hair – and the power within the wind – was almost a religious experience. I was hooked, big time.

There were differences, of course, between 40 feet and 130. The smaller boat felt almost alive compared to the much older J-class boat I’d sailed on the week before, and I found myself mesmerized by the brisk sensations of the Swan. I didn’t know it at the time, but Jennifer studied my face that day, told me she was reliving her earliest sailing experiences by watching my reactions to the shifting winds. She was very dialed into me, you could say. But there was always a hard edge to her, to the way she studied people, and I was in no way dialed into her enough to catch that. Not then, anyway.

We turned the boat over to her new owner and drove down to Newport Beach, stopped and had a late dinner at The Crab Cooker, and after we dropped off the girls she drove me back up to the marina, and I told her about Pops then, about what my grandfather really meant to me, and she remained quiet all the while, let me ramble-on until we pulled into the lot where I’d left my car. She parked and turned to face me, leaned the side of her face on the seat and stared at me.

“What are you going to do now?” she asked. “Try to go on tour?”

“I don’t think I can do that. I need to be here now, to be with him.”

She slowly nodded her head. “I think so, too. You need anyone to talk to, just call me. Any time, day or night. Got it?”

I looked her in the eye. “What happens if I fall in love with you?”

“If?” she said, grinning.

“Okay. When I fall in love with you?”

“Are you sure you haven’t already?”

I can still feel that moment, even now. Like it was the most important moment of my life, and those precious feelings are still right there with me, wherever I go, despite the gathering storm.

“I know exactly when I fell in love with you,” I said – still looking in her eyes.

“Oh?”

“About a minute ago. Before that I was fighting it.”

“I know.”

“You know?”

“I think you’ve been fighting it all day. I know I have.”

I smiled, felt palpably relieved, so I asked: “You want to go meet Pops?”

She nodded her head again. “Yeah. I think that’d be a good thing.”

So we went. She met Pops and he loved her too, which was, yeah, kind of a good thing. It was the first time I’d ever come home with a girl, and the moment wasn’t lost on us, either. Terry was a little coy about the whole thing, a little too reserved one minute then effusive the next, but by the time we left I felt she’d come around too. Back then I could never quite tell what was on Terry’s mind. I still can’t.

“So, you’re the one?” Pops asked her as he walked us out to the driveway, and Jennifer didn’t know what to say just then, but I did.

“Yeah, Pops, she’s the one. You mind if we run off to Vegas and do the deed, or did you want us to do it here?”

“Let’s all go to Vegas,” he said. “I can hit the tables after, and who knows, maybe I’ll get lucky.” This he’d said for Terry’s benefit, his way of popping my grandmother lightly on the tail-feathers.

And we all laughed at that, even Terry, but we weren’t fooling anyone. Not by a long shot. Life’s never as simple as it seems, especially when the slippery slope is staring you right in the face.

“He’s kind of cool,” Jennifer said as we drove back to the marina. “He’s like old school Hollywood, I guess. At least that’s what comes to mind.”

“He is that. Not many like him left in this town.”

“Thanks for letting me meet him. Even if you were joking…”

And I looked at her just then, like maybe I had been joking, or – maybe I hadn’t. And she looked at me, too. Anxious, maybe? Or was she hopeful?

“You were joking, weren’t you?” she finally said.

“We’ve known each other a week,” I shot back. “Maybe it would be nuts, but I haven’t been able to think about anything else for days.”

And when she nodded her head she also looked down, obviously thinking about the implications of my choice of words, yet she didn’t say a word. There were a million unheard cries for help in that look, too, only I wasn’t dialed in enough to understand all that.

“What about you,” I asked. “Am I too late? Already spoken for?”

She looked away and I could see a wave of pain resurface, then as suddenly pass. “I was serious about a guy in high school,” she said – and I thought maybe a little too evasively, “and we kept dating after graduation, and even after I went to Stockton. He went to SC and I think he decided it was time to move on. We broke up a few months ago – well, just before Christmas.”

“Do you know what happened to him at SC?”

“I heard he met a girl. ‘Someone less complicated than you,’ was the way he put it.”

“Jeez. What a nice guy.”

“Yeah, you could say that.”

“No one since?”

She shook her head, growing more uneasy as she skirted around the real cause of her pain. “He messed with my head, Aaron, and I’ve been having a hard time getting over it. We’re seeing the same shrink, you and me. Did you know that?”

No, I didn’t, but it kind of made sense now. “Jenn, did something bad happen?” I asked.

“Pills,” she said, tearing up a little. “I took a bunch of pills. My roommate found me in time, and the RA got me to the ER. They pumped my stomach, that whole scene, and I came home after that. I’m not real sure I want to go back, ya know…?”

“You’re not going to finish your degree?”

“I don’t know. Maybe.”

“Anything else you want to do?”

“I like sailing, that’s about all though. Dad put up some money to help get a sailboat company up and running, and I’m going to start working in their marketing and sales department this summer. I guess we’ll see how it goes.”

“Sounds kind of fun. Not a lot of stress, anyway, and doing something you love.”

“What about you? You going to keep playing?”

“I don’t know. Composing, anyway, or maybe producing. I like working in the studio. We have a session player, a musician who’s preparing to go out on the road if I can’t handle our next concert.”

“Where’s it going to be?”

“San Francisco, at the Fillmore. Some cook people will be there, too. Hendrix is going to play, and a new British group, too. Should be a scene.”

“Wow…sounds kind of crazy, in a cool kind of way…”

“You wanna come up?” I asked, treading carefully now.

“You sure you want me to?”

“You know, we were talking about getting married a few minutes ago. Nothing we’ve talked about has changed, as far as I can tell.”

She looked at me again and I could see it written all over her face, in the cast of her eyes. Not quite shame, but maybe a real close cousin. Something deeper than embarrassed, anyway. Something like fear and regret. Trying to kill yourself – and failing – had to be hard to deal with by yourself, but to lay it all out there like she just had? She either had guts or she wanted to see how real I was. The thing is, I wasn’t running. Maybe it was my own anxiety issues, the whole thing with being abandoned, but I think I started to understand her better after she opened up a little. I don’t know the how or the why of these things – at least I didn’t in those days – but understanding where her pain came from made me feel closer to her, like the connection we’d made somehow got deeper. And by that I mean a deeper kind of falling in love, but also like I wanted to take care of her. I know that seems a little off, but when I saw her vulnerabilities I wanted to be stronger for her, so I could help her carry the load.

And I think that was a turning point for me. Seeing myself as someone strong, someone other people could depend on. Like tumblers clicking just before everything falls into place, suddenly things seemed more clear to me.

Jimi Hendrix \\ The Wind Cries Mary

Anyway, we drove to the marina and walked around for a while, and a clinging fog rolled in as we looked at boats and talked about sailing – and at one point she took my hand in hers and I remember how good that felt, though maybe we were in a fog of our own making. I remember that the thought of letting go of her in a minute or two, and then watching her drive away to Newport Beach without me felt disconcerting. It was damp out, a soggy kind of damp, and we stopped in front of a hotel in the marina and looked at one another, then we took each in our arms and we just held on. I know I felt like I wanted this moment to go on forever, but then she kissed me, told me that she loved me and suggested that maybe we should go get a room.

I remember those eyes of hers. Looking up at me deep inside that moment, how hesitant they were, yet so full of lingering intensity. She was so insanely gorgeous, probably the most beautiful girl I’d ever known, and if that asshole boyfriend hadn’t fucked with her head so thoroughly I thought that maybe she could pull out of her depression – or at least I kept telling myself that over and over during the next few weeks. And hell, who knows, maybe I really believed it, too, but she was fragile, real fragile. And yes, she’d had a real breakdown, but most everyone takes a rough breakup hard. To be honest, I think I knew there was more to her state of mind than just a breakup, but then again I always thought I was seeing just was the tip of the iceberg. I felt that way right up to Honolulu, but I’m getting ahead of myself. But that other truth remained: I liked the idea of taking care of her, though the reason was a little less obvious to me. Of course, my flawed reasoning is easy to see now, in hindsight. Our mistakes are like that, I reckon.

Years later it hit me. Feeling stronger about myself was motivating me all the time – because, even as a little kid, and maybe especially because I was a kid, when you lose your parents strength is usually in short supply. Pops was a great surrogate, don’t get me wrong, but in those days what little self-esteem I had seemed to rest on shaky ground.

Or maybe all that shakiness came from living near the San Andreas fault.

+++++

I drove up to Berkeley a few days after that encounter, as it was time to start rehearsing for our Fillmore gig. The ‘feeling stronger’ vibe I’d run across with Jenn stuck with me, too, and I felt good about going out on stage for the first time in my life. Deni picked up on that new vibe, too, and as a result she was almost ecstatic about the whole Jennifer thing. Rehearsals went great and I picked Jennie up at SFO the night before we were set to play, and we went straight from the airport to The City to listen to The Nice.

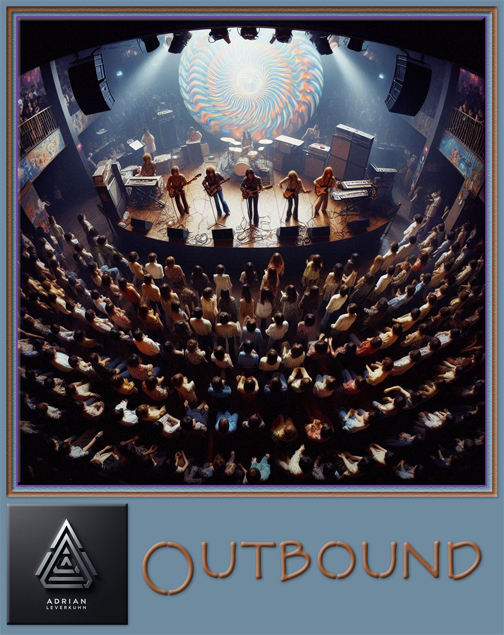

There really weren’t many keyboardists trying to bring new technology out of the studio and to the stage, but Keith Emerson was creating quite a storm with his stage act, and everyone was hanging around the Fillmore in this haze of expectation – waiting for him, of course, but Hendrix too, who was coming on after The Nice.

Hendrix was the current Rock God du jour, but for any keyboardists watching that night, Keith Emerson was a revelation. Here was someone, finally, bringing classical structure to rock, and while his rendering of Bernstein’s America was electric, what caught me was a piece called the Five Bridges Suite, which fused classical with both jazz and rock. About halfway through that piece I started to look around at the crowd and found a kind of swaying trance had taken hold. People didn’t want to dance now, it was more like they’d been transported somewhere else, someplace deep within Music, and deeper than I’d ever thought possible. Even Jennie said “Wow!” when those guys wrapped up and drifted off into the crowd…

But when, finally, Jimi came out the place erupted, and when The Experience started in with Fire you could understand what all the electricity was about. I hung on ‘til they finished up with The Wind Cries Mary, and when I looked around the place I could feel something else passing through the crowd, something that was initially hard to put a finger on. What first struck me was the power such music held over the crowd. Something awesome and huge lurked in the shadows, a force I’d never reckoned with before, yet as good as Hendrix was what got me most of all was Emerson’s fusion of styles. I watched him for a while, long after their set was over, and he was watching the crowd too. I felt a sudden surge of empathy for him as I watched, because like me he was lost inside the wonder of the moment, and he too seemed a little confused.

One other thing that hit me just then, too: the amount of pot hanging in the air. From fifty feet back the air was literally purple, and with the multi-colored stage lights bathing the area around Hendrix the atmosphere was otherworldly. I knew a couple of cops were working the back of the crowd, but I wouldn’t have wanted to be them. After the ‘free-speech’ demonstrations across the bay over the past few months the sense of anger and purpose was palpable in that crowd, so there was another ‘something’ hanging in the air apparent that night, and it wasn’t exactly empathy for cops, if you know what I mean. And that vibe was quickly becoming the raw underbelly of the acid rock scene at the Fillmore. That ‘other’ something in the air. It was beyond revolution, more like anarchy waiting to be unleashed, and when the raw power unleashed by Hendrix washed over that crowd, you could sense a new undercurrent of anger growing by the minute.

And both Emerson and I were not just feeling it, we were beginning to see that power as an untapped force. And music was a key to unleash that power.

Sure, a lot of the music in the late-60s was all touchy-feely, ‘peace and love,’ but there was an awful lot of anger in the air after Reagan and Meese clamped down on protests at UC Berkeley, so there was also this Hell’s Angels vibe going around the Fillmore, too, an undercurrent of outlaw violence rooted in the desire to burn everything to the ground. That was San Francisco in ’68, yet I suspect powerful music has always been like that. Like the way Wagner lived through and inspired European revolutions in 1842 and 1848, and how the pure unbridled force of his music became the soundtrack for the Third Reich.

So yeah, Jenn was there and she was a part of me, and that too is something I remember thinking about a lot these days. But there was something else there. I felt there were more than a few people working the fringes of the crowd who were there to stir the pot, who wanted to create something new out of this new force, but it also felt like this Fillmore fringe didn’t really care who got burned along the way. So, yeah, I think there was real anarchy working inside this audience, like this new fringe wanted their parent’s world to dissolve within that purple haze. A few years later it hit me that most of these emotions were rooted in infantile rebellion, like the tantrums of spoiled children.

Yet, you know, sometimes even children are right.

That spirit was in the air, too. Even in the music. Our parent’s forms and structures, subverted and inverted, creating something new and anarchic, yet inclusive. Like the Beatles opened the doors to polite society and now the riffraff were pushing their way in – burning babies in Electric Ladyland. Music was, right before our eyes, becoming more political than it had in a hundred years, just like Wagner politicized opera in post-Napoleonic Europe. If you think that’s trivial stuff, just consider for a moment that Marx grew out of Wagner’s music, and yet so did Darwin. They were contemporaries, and each in their way was a revolutionary, but Wagner’s music was like a match around a powder keg.

So yeah, something was stirring deep inside the underbelly of that crowd. Something big and noisy, but that new creature was ugly, too, and I could feel it stirring in the shadows. There was a glowing meanness in that purple haze, and fires were starting to burn along the fringes.

Those fires defined my generation. Just as they defined our music.

+++++

We were the first gig up the second night, so we set up early and I looked around the place while Pete helped hook up my stuff, my Moog and Mellotron, and my backbreaking, 400 pound ‘Silvertop’ Fender Rhodes. The air inside was clear now, and the room didn’t look all that big – much less like a place full of wild magic. Just a room, I thought, not unlike the other gigs we’d played around this city, yet I had felt those forces the night before. Emerson had too. We talked after Hendrix left, talked about the vibe we’d discovered, and we talked in epochal terms about music shape-shifting to the needs of the moment. About the politics of music. We talked Nixon and Vietnam and John Wayne and about the image of a girl who had put a flower down the barrel of a National Guardsman’s rifle. Everything was linked, he said, but the links weren’t easy to see – unless you knew where to look. Music had to become the fabric that joined a lot of disparate factions, yet only a few musicians had tried to claim a place as leaders of this movement. Heady stuff, and even Jenn seemed caught up in the moment. Emerson was a philosopher-king if ever there was one. But then again, so was Wagner.

Yet standing up there on stage looking out over that empty room it was hard to see music as anything other than a diversion. Maybe we were just a sideshow to the real action. I’d just read Jerry Rubin’s ‘Do It!’ – a true Bay Area anarchist’s manifesto – and I wondered: could music really carry the weight of so much revolutionary zeal, shoulder such a fragile burden? Or would music fragment the way society seemed to be fragmenting?

Even when I worked with Deni the tendency to fragment was there – this impulse to fly apart, to head off in uncharted new directions, and I’m pretty sure there wasn’t some unseen political hand pushing us towards a grand unified theory of musicians leading a movement. Most of the kids on stage were just that: they liked to play the guitar or the keys, and yes, egos got big under that tent. We got off on making music together, yet I can’t recall ever sitting around and saying “Wow, did you see those riots on campus today! We gotta write about that!” Nor did I ever hear anyone claim to write music to incite violence. Like I said, those people were working the fringes, playing the shadows, and – usually – not on stage.

Yeah, yeah, but there was one anthem out there that contradicts all that vibe, and I loved it. For What It’s Worth, by the Buffalo Springfield – and maybe that’s the vibe Emerson was channeling that night as we watched Hendrix play the crowd. We were in our own purple haze, inside his creative creative haze – and maybe that’s why the idea hit the way it did: that I had always seen music as a reflection of events, not a means to change things. But standing up there looking at the empty room one of those creative impulses hit, and it hit me right between the eyes. Maybe music could be both. But then, and maybe because I’d never really seen my music as such – I had an idea. I wanted to do something unexpected – and out of character – something like an experiment in real time.

I hadn’t played Lucy-Goosey in years. My first hit song had already dissolved into the receding fog of early Beatlemania songs like of I Wanna Hold Your Hand and She Loves You, Yeah-Yeah-Yeah, yet my song was still out there, buried somewhere in our collective unconscious – so the thought occurred: what if we…as in Elektric Karma…played with Lucy-Goosey. Turned her prepubescent bubblegum into something tinged with just a hint of insurrection.

Deni was immediately entranced by the idea, too, and she came up with a few bridges to make the pop refrains seditiously relevant again. Lucy was going to go from bubble-gum chewing sycophant to radical anarchist on stage that night, and the whole thing was taking shape in a burst of creativity that had come out of – where? You tell me. You want to go all Jung on us and tell the world that yeah, there really was something to this whole collective unconscious thing?

Anyway…

When the lights went down a slide was projected on the wall behind the stage, an image of that girl sticking a daisy down the barrel of a national guardsman’s rifle, and I walked out and got behind the keyboards – then turned and looked at Jenn standing in the shadows backstage and we exchanged hopeful smiles, then I turned to face the sea of faces and raised my fist – but as the room went black – and all that remained was a single bright spot shining down on me, with that image of the girl and her daisy hanging back there, back behind the purple haze.

I started with the simplest piano refrains from Lucy-Goosey and the sea of faces went silent as curious expectation replaced hyped anticipation, my piano playing almost in chopsticks mode: simple notes even a child could play, deliberately awakening something lost in memory. Something innocent and childlike. Our lead guitarist stepped out and another spot hit him, and he started echoing my simplistic melody. Deni came out next and the crowd erupted, then as quickly shut down as she started into an even simpler, quieter version of Pete’s original lyric, and she picked up a small harp and echoed my childlike notes as the lights faded, leaving only the image of the girl with the daisy – which soon faded to black as my piano grew softer, then silent. In the darkness the rest of the band came out and when the lights flared we turned Lucy into a molotov cocktail throwing radical with what I’d say presaged a grungy-heavy metal infused sound – raging dark music that no one in the audience had ever heard before – and the surge of energy out there was cataclysmic. I kept the simple piano melody going, but that was echoed by soaring, dark chords on the Mellotron, and with Deni’s inverted lyrics Lucy’s transformation was complete.

And I felt that transformation in my soul, too, like Lucy had just grown up. Like I’d just grown up. The insecure teenager died out there that night, and when we walked offstage an hour later I fell into Jennifer’s arms and held on tight, because I knew the ride ahead was about to get real intense.

+++++

Pops was a lot sicker than he let on, and he kept everything wrapped up and put away in a dark corner out of sight, so out of mind. Every time I called he was ‘fine, doing great’ – and Terry, my went along with this charade, and it worked – at least until we came to LA to play several concerts around town. I went home after our first night and when I saw him I started crying. I couldn’t help it.

“Do I look that bad?” he asked.

He looked like an orange scarecrow, only worse – because his mane of thick white hair was now a ragged mess.

“The color,” he added, “is from liver failure. I kind of like it, too. Like a walking traffic sign, don’t you think? When I walk out of the doctor’s office everyone stops and stares, waiting for the light to turn green.”

I felt sick, too, just looking at him, and then Terry told me he had at best a month I kind of fractured. Like I didn’t know what to think. Pops was my last link in the only chain I had to an almost invisible past, and without him I would be well and truly alone. There weren’t any brothers or sisters or aunts and uncles to fall back on, there was just me and Pops. I was going to be, if I remained alone and childless, the last of the line.

And that was the big question hanging in the air between us. In the air, apparent, you could say.

“What’s with Jennifer?” he wanted to know.

“We’re good,” I said, but there was something else hanging in the air. That whole fragile thing. She was depressed more often, and when she started going down that hole she turned to dolls to pick her back up. Dolls, as in The Valley of The. Pills, in other words, Uppers. And here I need to digress a little. I didn’t do pills. I didn’t smoke – anything. I didn’t drink much either, because I didn’t like the whole idea of losing control. I know, like the idea we have some kind of control is an almost comic thought, but the point is we do have the ability to control some things, and losing what little I had was to me a Very Bad Thing. I tripped all I wanted when I disappeared inside my music, but I could come out of it intact and lucid. I had seen Deni disappear down the LSD rabbit hole and not come out for days, and that scared the shit out of me. We’d been through two lead guitarists over the course of a year simply because one drug or another had taken them someplace they just couldn’t come back from, and I’m sorry, but I wasn’t going to go down that hole.

So when I saw Jennifer headed down the same road I told her it worried me, and she angrily told me to fuck off. So I did. I took her out to SFO and put her on a plane back to her father and told him what was going down, and what I heard back from him wasn’t worth mentioning, because he’d thought he was done with her and wasn’t at all happy to have her back under his roof.

I started spending more and more time in LA, spending as much time with Pops as I could, and my understudy started filling in more often as Pops started his terminal decline. I had previously agreed to go on our next gig in Cleveland; I was there when Terry called my first morning there, and she told me to come home right away, and it was just hours before the show that night so I called Deni and told her. She came to my room and we talked, and she told me to take my time, that they’d manage without me and I held her for the longest time. We’d been together as a group for more than two years by then, and I realized she was about the closest thing to family I’d have left – and I told her just that.

“I never wanted you to be my brother, Aaron,” she told me then. “All I know is we fit, ya know? We work well together, like I always imagined a husband might, ya know?”

“Those two days, you still think about that?”

“Yeah. Love heroin. I’ll never forget. I’ve never loved anyone like I loved you then,” she sighed, and before I knew it she was crying. “God, I don’t want you to go. Something’s going to happen to you back there. Something fuckin’ big’s coming, and I feel like it’s going to crush you, man.”

“I don’t know what I’m going to do without him, Den. I’m scared, and with Jenn gone? I don’t know, man, I don’t know…I mean I really don’t know what to do…”

“I’m here. Don’t you forget that.” She looked at me and we kissed, I mean like the last time we’d kissed, and that kiss was full of all these bizarre kinds of electric charges flickering on and off like lightning all over my skin, then she looked at me again. “I love you, ya know,” she sighed, then our eyes met, and this time we were hovering over the abyss, ready for the fall, but then she pulled back and ran from the room.

I got my bags together and made it out to the airport in time to catch a one-stop to LAX, and made it to the house a little after midnight. I went to Pop’s room and we sat and got caught up while Terry left to put on some tea, but she came back a few minutes later, her eyes full of a different kind of grief. She turned on the TV and there were news reports of an airplane crash, a flight from Cleveland to Buffalo, and a hundred and fifteen people, including all members of the rock group Electric Karma, were feared dead.

Can you flash back to when you were three years old?

Because I blinked back from the waves of fear washing over me, recoiled from the very idea Deni and all my mates were gone, and that the sum total of their existence had been wiped from the slate in the blink of an eye, yet the pictures on the TV told a very different story. A midair collision about a mile out over Lake Erie, and the 707 had burst into flames and fluttered down to the waves, then all that we had been simply slipped beneath the water and was gone.

Pops died the next day.

I wasn’t a three year old that day, but it hurt just the same.

+++++

Jennifer thought I was on the plane, that I’d died that night, and she came undone. Razor blades this time, and she’d meant to take herself out, no doubt about it. By the time I called their house the next morning the damage had been done, though I didn’t find out just how bad that damage was for a few more hours. When I talked to her father later that day he sounded both relieved and furious, and I told him I’d be down as soon I could. He said he understood and we left it at that, and Pops slipped away from his morphine induced coma before I left. We didn’t really say goodbye, but when I held his hand I could feel him respond to my words. When I told him he meant the world to me, and that I’d miss him he squeezed my hand, and I could hear him talking to me through the years. All the talks we’d had were still right there, and Terry was with me, holding on to me, when he finally slipped away.

She was English, our Terry, and she’d had a good run in Hollywood for a while, made a half dozen romantic comedies with the likes of Cary Grant and, yes, Jimmy Stewart, so when Pops moved on it was a big deal in Hollywood circles, yet the death of my bandmates cast a long shadow over the whole affair. Everyone knew about Pops and me, how tight we were, yet Terry was the big surprise – to me. I’d never really appreciated how close they were, but one look at her and you knew it wasn’t an act. She stopped eating for a month, literally, and wasted away to nothing – and then I had to admit I really felt something for the woman. She wasn’t just Pop’s third wife: she, too, had now become the one last link I had to him, one I’d never even realized existed, and all of a sudden I was scared she might leave me too.

And let’s not forget Jennifer, lying in restraints in a psychiatric hospital tucked deep inside the hills above Laguna Beach. I started driving down to Laguna every other day, then every morning, and I spent hours with Jennifer before I drove back up to Beverly Hills, back to Pop’s house, where I tried to pull Terry out of her funk.

Yes. There’s a pattern here. You’d have to be blind not to see it.

And so, yes, of course I missed it.

About three weeks into this routine I decided to take Terry with me down to Laguna, to try to get Terry to see what the contours of falling into a really deep depression looked like, and it worked. Yet that day also marked a big turnaround for all of us, because she reached out to Jenn and they connected.

Like a lot of people around that time, I’d seen 2001: A Space Odyssey, and to me that moment in Laguna felt a lot like one of the key passages in the movie. When Hal goes bonkers and cuts Frank adrift, and Dave goes after his tumbling body in the pod – helmet-less. I wasn’t sure if I felt more like Dave or Frank, but I knew everything was tumbling out of control – yet as I was the only one who could set things straight I had to be Dave.

Like Pops had set me straight after my parents died, I knew it was my turn at the controls, and I didn’t want to let either Pops or my old man down. Hell, by this point in the game I didn’t want to let Jennifer’s father down.

Yet whatever was wrong with Jenn, I was also beginning to see that her old man was behind a lot of her anxiety – so when I’d put her on the plane back to OC I had, in effect, sent her back into the snake pit.

Nope, I was not going to do that to her and then just walk away. When you tell someone that you love them, you don’t treat them like that. It’s a simple proposition, really. Either you mean what you say or what you say is meaningless, and now I took that to heart. I was starting to take a lot of things to heart. Simple things like love and duty, and most of all, truth. Simple things like that suddenly seemed more important, more in my face. Death can do that, you know? Make hard things easier to see, easier to understand.

At least I liked to think I understood what was going on.

So, let me tell you a little more about Terry before we visit my own little snake pit.

She met Pops when he was in his sixties. They got married when she was, well, let’s just say thirty-ish – maybe. She was forty-something now – maybe, and every bit the Hollywood starlet she had ever been, and in the aftermath of her decision to rejoin the living she decided she was either going to move back to London and take up work on the stage again, or make another movie. Or maybe a bunch of movies.

And she wanted to know how I felt about her moving back to London. Specifically, did I want to her remain in LA, to remain a part of my life, or did I want her to move on.

Mind you, I barely in my twenties so I wasn’t a rocket scientist as far as people were concerned, nor was I exactly a babe in the woods, but recall that I’d never found it easy to think of Terry as my grandmother. She came into my life when I was not quite a teenager, a time when she was widely considered one of the most beautiful women in the world, and not just because Life Magazine had proclaimed her so. Let’s just say I’d spent a few sleepless nights over her and leave it at that, and I think you’ll grasp the contours of my own little dilemma.

So, I told her in no uncertain terms that I didn’t want her to move on. I told her she was an important part of my life with Pops, and that she would always be important to me. The problem I didn’t quite wrap my head around was that she didn’t see us that way. She’d spend ten plus years married to a man who hadn’t been able to perform his marital duties for a long time, and she was just entering her prime. The biggest part of the problem was the simplest, most elemental part, too. I still found her deeply attractive, and devastatingly so. And she knew it. Hell, everyone was attracted to her.

There was a part in a new movie coming up, the role just being cast, where she’d get prime billing next to some very big names, and so she’d gone to the audition at Fox dressed to kill. When she came back she was elated; she’d gotten the part and shooting began, in France, in three weeks. She wanted to celebrate and so we went down to The Bistro – where her landing the part was all the buzz. Everyone came by our table to congratulate her – and offer their condolences vis-a-vis Pops – and everyone looked at me like ‘who the devil are you.’

Why, I’m her grandson – didn’t you know?

Oh, the look on her face was priceless.

What followed was three of the most regretfully confusing weeks of my life, and I’ll spare you the details. Sex was not involved, thankfully – or regrettably, depending on your point of view – but the whole thing was an emotional hurricane that left me drained. After the services, I had Pop’s estate to settle, cleaning up the house to get out of the way, and helping Terry with her lines. And so for almost three weeks straight everywhere I went Terry was by my side. And when I visited Jenn, she began to pick up on a new vibe, too.

“Are you sleeping with her?” she asked me one morning after I’d just walked into her room.

“What? Who?”

“Terry.”

“G-a-w-d! Geez, no Jenn! Are you kidding? No way!” And…I wasn’t lying. Not exactly.

But I guess the way the word ‘no’ came out implied an air of finality, because Jenn never brought up the subject again. And, a few weeks after Terry left for Avignon, Jennifer was discharged and moved in with me, in Pop’s house.