Ah yes, so Happy Christmas and Merry New Year, or…have I got that wrong…?

A modest chapter today, long enough for a cup of tea, too brief for popcorn. A few zigs where zags might have been expected, but c’est la vie.

Seen this bit of wordplay, or should we say Coldplay? Not a helluva lot to say after that, you know?

5.15

He closed his eyes as even the images came for him. Honfleur, Amsterdam, Paris at Christmas. Rupert and his Swan. Dina and Rolf.

Then he heard that music. It played and played, the same nightmare soundtrack. He tried to turn away from the sound but now it was everywhere: ‘Yo-ho, yo-ho, a pirates life for me…’

“Oh, no, not again…” Henry Taggart moaned as he opened his eyes and looked around, and then his mind connected with the ancient female by his side.

‘Others call,’ he heard the orca say to him.

Then the images, again. People he’d never seen, places he’d never been.

“This is absurd,” he said to the old orca. “Everything is meaningless here.”

‘You see only one. Must see many.’

“Many what?”

Her face slipped underwater and in an instant the old orca was gone. He looked around, saw only darkness. No land. No ships or sailboats.

But overhead?

He saw Orion. At least it looked like Orion. Only here, the massive hydrogen clouds were closer than close. He felt like he could reach out for one and grab hold…

“This can’t be right,” he sighed, and in the blink of an eye he was in the Seine again. Honfleur just a few yards away. And the water was cold as hell. People on the shore, in that park, were waving at him. He grew lost in waves of remembering. Cancer. Dying, then death.

So? This is death?

‘You see only one. Must see many,’ the old orca said again.

He jerked around, saw his old friend. “Why? Why can’t they leave me to my death?”

‘Need great. Time breaks.’

“Breaks? What breaks? What do you mean?”

‘Great pain for all. Must go.’

More images came. Sea battles between great navies, but with strange vessels like Greek triremes in one image, then Ohio-class ballistic missile subs in the next. Then men on horseback charging helicopters, men in starships battling vast swarms of black, insect-like monsters…

‘Understand? Time breaks.’

“Understand.”

‘Others call. Must leave.’

Taggart looked around again and saw only stars, millions and millions of stars. First there was no pattern, no movement, then there was nothing but movement. The stars began to swirl, forming little clusters. Clusters began to swirl, forming new groups, new clusters, and for a moment he thought he was looking at the formation of the universe, like time had reset and everything was starting over, then he saw the pink sphere and her careworn eyes searching for his.

+++++

“It’s going to happen, you know, and there’s nothing you, or anyone, can do to stop it.”

Deborah looked at her father as he paced around his library, and now she was sure he was as mad as a hatter.

“Look at them, Deborah. Just look at them!” He pointed at a wall of television monitors, dozens and dozens of news feeds coming in from all around the world, each feed full of descriptions of chaos and mounting human misery. Climate breakdown, innumerable hordes of people from undeveloped countries fleeing to the industrialized north, civil wars, famine, disease literally raging on every continent save Antarctica. Trump’s walls overrun. Helicopter gunships patrolling the border with Mexico, on some days hundreds of people killed trying to push their way past border checkpoints. Saudi Arabia’s grand experiments in planned megacities collapsing under the energy demands of 140 degree temperatures – at night. People from southeast Asia making their way north, first into China, then pushing their way to Siberia, anything to escape the broiling humanity falling by the wayside. “At any one moment now almost three billion people are on the move, trying to escape the heat, or trying to move inland as coastal cities disappear under rising tides. Snowpack disappears, rivers and reservoirs turn to sand, and farmland blows away. Where will it end, Deborah?”

“And yet here you are,” she said, “stoking the fires…”

“Governments have failed us, Deborah. Democracy has failed humanity.”

“I see.”

“No, you don’t.” Ted Sorensen turned and looked at his daughter. “You don’t because you can’t. You were brainwashed from the beginning to see democracy as the lone just path, the righteous way to freedom, even as democracy stripped your freedoms away one by one, even as democracy tried to sell itself around the world as the only way forward. And Hell, why not? The Marxists were out there doing exactly the same thing, and failing just as miserably…”

“And your television networks are somehow going to…”

“Yes? Go on?”

“You’re going to fix all this?”

“Fix it? Hell, no, we’re not going to fix it, but that’s the point, Deborah. These systems can’t be fixed, yet we’re locked into perpetual combat between these two competing socio-economic models, between capitalism and communism, and between these two ways of thinking about civilizational progress.”

She shrugged. “So, what are you up to?”

“Ever hear of the term ‘accelerationism?’”

“I’m not sure. Maybe some kind of alt-right thing?”

Sorensen sighed and looked away. “They borrowed the term, I think, but what I’m talking about originated in the 70s, but rather than describe the term I’d rather ask that you read a couple of books and essays.” He went to the reading desk in his library and picked up three books, then carried them over to her.

“Homework again, huh Dad?” she said as she took the books from him.

He smiled. “You might think of them as such, but I would hope that you find something in these words more of interest to you. Now, we’ve got dinner to think about. Does trout amandine sound about right? With a spinach soufflé? And I have a Chilean Riesling that really is quite special.”

She looked at one of the books and groaned as it was in French: Capitalisme et schizophrénie. L’anti-Œdipe, then she looked up at her father. “Is this some kind of medical text?”

He smiled. “Not hardly, though one of the authors was a psychoanalyst. The other was a philosopher, and together they came up with a very different way of looking at the world.”

She put that book down and looked at the second, a book of essays. “The Dark Enlightenment, by Nick Land,” she said. “And what is Mr Land selling?”

Her father smiled again. “The idea that freedom and democracy are in truth antithetical to one another.”

“Oh? Truly?”

“Yes, truly. And he maintains that capitalist corporate power makes the best organizing principle for a working society, because that type of culture best leads to true freedom. That may sound fringe, but Peter Thiel, as I’m sure you’ll recall, mentored a younger J D Vance before he drove these two books straight into Republican orthodoxy, and then right into the White House.”

“I see.” She put this second tome down and looked at the third. “The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, by Benjamin Bratton? Okay, what’s the low-down here?”

“Bratton discusses how rapidly evolving information technologies undermine what are in fact ancient ways of organizing societies, and how these anachronisms are being distorted into irrelevance by rapid advances in these technologies.”

“Sounds yummy.”

“Oh, hardly, yet the process has been underway since long before you were born.”

“And so you, and this whole Eagle Networks thing, have been…?”

“Collapse is inevitable, Deborah. We’re just helping things along, trying to guide events to, hopefully, influence a just outcome.”

“You make all this sound so benign, yet…”

“Yet what you’ve seen to date hardly seems benign.”

“That’s about right.”

He nodded gently, then walked over to a large window that looked out over a huge lake, and to a spectacular mountain range in the distance. “That’s because what was first envisioned started out in one direction, but this has been – well, I’ll put it to you this way – in any organization that manifests great power, there will always be power struggles…”

“And there’s one going on now?”

He nodded. “Yes, yes there is. And a very big, very dangerous situation is developing.”

“Dangerous? How so?”

“Unpredictable. Things are rapidly becoming unpredictable, and I fear all this effort will soon dissolve into unrestrained chaos.”

“Dad? Are you saying you need my help?”

Ted Sorensen looked away, tried not to remember the nights when she was little. Those terrible nights when she had disappeared while taking a shower, only to reappear minutes later inside a cascading rush of shattered sea ice and cold seawater, and then evidence that she had visited the Titanic in the moments just before that fateful moment. “I do,” he sighed. “Very much, as a matter of fact.”

She got up from her overstuffed reading chair and went to him. “Do you know that’s the first time you’ve ever said anything like that to me, Dad. I don’t know what to say.”

He took her hand in his, though his eyes never left the mountain beyond the lake. “I know, Deborah.” He shivered, then shook his head. “I’m afraid it won’t be the only time. I know this will be difficult, but you need to trust me; things are not quite as nefarious as they might at first appear to be.”

“Okay, Dad. What can I do to help?”

“I need you to meet someone. An associate and, I dare say, a good friend of mine. His name is Peter. Peter Weyland.”

+++++

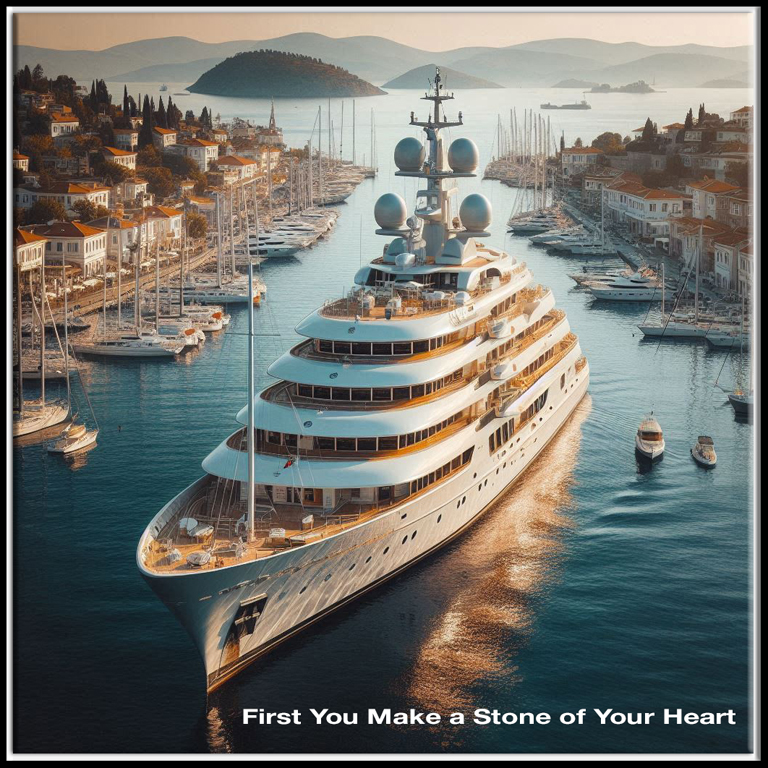

Baris Metin Didn’t need binoculars to see that the tiny harbor was too small for American Eagle, but as Dr Weyland wanted to tie up at the stone quay, it was Captain Mendelssohn’s job to maneuver the huge yacht into harbor, to get the job done. And to make matters worse, Weyland was on the bridge this morning, watching them both. Baris adjusted the forward scanning sonar to get a better picture of the shoaling seafloor ahead, while Captain Mendelssohn used the joystick to make tiny course corrections. ‘Eagle’ was a hundred and seventy feet long and her keel was fourteen feet beneath the waterline, yet the water’s depth at the quay was just sixteen feet. The bigger problem was the turning basin near the quay, which simply wasn’t large enough to handle a boat this length.

“Captain,” Baris sighed under his breath, “I really do not recommend you do this.”

“Why is that, X-O?” Weyland snarled, stepping closer now, right into Baris’s space.

“Sir, there are too many small vessels moored near the turning basin, and even without them in our way this ship is simply too long.”

“And what do you recommend we do about that, X-O?” Weyland said, now somewhat less annoyed.

“Anchoring out would be safest, sir. Or we could back down through the harbor, all the way to the quay.”

Mendelssohn shot him a quick, sidelong glance. Backing a yacht through this crowded harbor would mean relying on video cameras and all the other instruments up here on the bridge while using the aft docking station above the swim platform to actually maneuver the ship. Doing so wasn’t impossible, merely very difficult, but this would also be a good test of Metin’s skills – and he knew that was exactly what Weyland wanted out of this exercise.

“I want to be tied stern-to the quay,” Weyland growled. “You’ve been working up here for a month now. Do you think you can get me there or not?”

“Yessir, of course I can. Captain, permission to go to the aft steering station?”

“Go ahead, X-O,” Mendelssohn sighed, more than a little surprised and grinning as Metin left the bridge.

Weyland waited a moment then turned to Captain Mendelssohn. “So, you’re sure he can pull this off?”

“If I didn’t, sir, I wouldn’t even let him try.”

“This really is a beautiful setting. I wonder why I haven’t come here before…?”

“Well sir, Portofino is a little touristy, on the beaten path, I guess you could say. We’ve always tried to steer clear of such places.”

“Sorensen’s orders, I take it?”

“Yessir.”

“And so here we are, sent to fetch his daughter…”

Mendelssohn opted to remain silent, and he sighed in relief when Weyland went out onto the starboard bridge deck, no doubt to watch all the people in the tiny village staring up in awe at his massive ship. Vanity, pride, whatever you wanted to call it, Weyland had it – in spades.

+++++

Weyland stood on the aft deck, watching Metin extend the hydraulic passerelle to the quay, in spite of himself admiring the man’s skill. Metin seemed in his element out here, happy, almost content. He walked over to the starboard rail and looked down on three sailboats docked at the quay, and he waved absently at an old man and a springer spaniel on the closest one, then strode off ‘Eagle’ like he was Patton taking Sicily once again.

Mendelssohn followed him down the teak passerelle with the Ship’s Papers, off to the harbor master’s office to take care of those tedious formalities, so he took a deep breath, admired the autumn sun and all the angled shadows retreating from the piazza. He looked at his watch, saw it was not quite noon so figured he had at least a half hour before Deborah Sorensen arrived. He walked over to a gallery, saw several interesting paintings on display through the window so went inside. A few mundane abstracts, a handful of predictably banal harbor scenes by local painters, but an odd piece tucked away in a small alcove all by itself. The painting was small, perhaps ten inches square but even from across the room he could see that this painting was the work of a master. It was of a small cottage framed by lavender and azaleas, very simple, but he could tell it was something special even before he saw the artist’s name. “A Sisley? Here?”

An old woman walked up behind him, yet she remained at a discrete distance and said not a word as she watched the man appraising the work, and after a few minutes he turned to her.

“If I may,” the man began, “has this been authenticated?”

“Yes, sir. By Merritt at the Royal Academy in London, as well as Sartre at the Louvre.”

“Where on earth did you find it?”

“He gave it to a friend who eventually moved here. The family has decided to part with it.”

“Do you have the letters of authenticity?”

“Of course. I’d be happy to get them if you’re an interested party.”

“If I may be so indelicate, what is the asking price?” She handed him her card. The price – fifteen million euros – was engraved on the rear. He took out his iPhone and snapped a picture of the painting then forwarded the image to a number in Geneva, and while he awaited a reply he asked to see the letters. He imaged these as well, and sent them on to Geneva. A few minutes later he had his answer, so he turned to the woman again. “I’ll need payment instructions, if you please?”

The woman opened a leather-bound portfolio and handed Weyland an engraved card from Credit Suisse, and he imaged this and sent this addition on to Geneva, then he called Britney, his personal assistant on the yacht, and told her to have Heinrich in engineering prepare lighting for the painting this afternoon, then he turned back to the woman. “Could you recommend someplace for lunch?” he asked.

“Yes, of course. Just next door, the Lo Stella. I’d be happy to call and tell them you are coming.”

“Would you? Thanks so much, and for your understanding.”

“It has been my pleasure.”

“Call my assistant when you’re ready for her to pick up the piece,” he said, handing the woman a card with his assistant’s information. “Her name is Britney, by the way.”

“Very well.”

“Well, thank you, and good day,” he said before he abruptly turned and walked out the door. He saw the sign for the Ristorante Lo Stella and decided to give the woman a moment to make her call, knowing that word of his purchase would spread like wildfire through the tiny village. He walked down the quay towards the boats moored at the far end, where he’d seen the old man and his dog earlier, and soon he saw the man’s boat was named Diogenes, and that brought a smile to his face as he walked along to the next boat. This one was named Springer, and it was locked up tight. The next boat in the line was named Sonata, and he heard someone playing the piano below and wondered what the tune was. He’d never heard the piece before – which he found strange as he thought he was well versed in the classical canon. He saw a young woman in blue surgical scrubs come up the companionway a moment later, and she made her way out of the boat’s center cockpit to the rear of the boat then walked down the passerelle and onto the quay. He smiled at her as she passed, taking note of the stethoscope around her neck, then he turned to watch her walk through the village. He looked at the yacht’s stern again and found her homeport – Annapolis, MD – painted on the port quarter, and that surprised him. He shook his head and walked back to American Eagle’s stern, perturbed that this Sorensen girl was already ten minutes late.

A tan Mercedes taxi appeared almost as if on cue, and the taxi came right to him. The well dressed driver, an ancient man of indeterminate origins, stepped out and opened Deborah’s door, then collected her luggage from the boot before he got back behind the wheel and disappeared.

“Miss Sorensen, I assume?” he said to the woman. He noted she was almost attractive, but she affected the studious academic airs of the perpetually insecure – right down to her round, tortoise shell eyeglasses and frumpy, worn out Doc Martens. Her smile was rather nice though her skin had the appearance of someone who had spent too much time out under the sun, and for some reason he thought her hands looked strong. ‘How odd,’ he thought.

“Yes, and are you Peter Weyland?”

“I am Dr Weyland, yes,” he said stiffly. “I’ve not had lunch yet and wonder if you’d care to join me?”

“Sure. Airline food still bites the big one, so I’m game.”

Weyland’s eyes twitched as her boorishness penetrated. “Ah, well, excellent. Do follow me.” After this suburban drone’s performance he was ready for a little fawning deference, so hoped the woman in the gallery had indeed called the Lo Stella. He walked under the green awning and noted the salmon colored stucco and green trim, even on the tablecloths here on the patio, and as an immensely old man approached, obviously the maitre’d, he sighed when he saw a complete absence of interest on the man’s face. Indeed, the man had a regal, almost leonine countenance that seemed to defy easy characterization. Ivory colored slacks, white shirt, subdued gold tie under a pale blue sport-coat, Weyland thought the old man exuded raw energy and was not at all what he’d been expecting.

“Dr Weyland, I presume?” the old man asked as they walked up. His smile was genuine, his eyes magmatic, full of hot power.

“Yes?”

“I see there are two of you? Would you care to sit out here on the patio this afternoon, or in the dining room?”

“Deborah? Any preference?”

“Out here would be great. I’ve been cooped up in airplanes for the last twenty hours…”

“Would you prefer some sun?” the old man asked, his concern obvious.

“Maybe, yes. That’d be great…”

The old man walked them down to the far end of the patio and pulled out her chair and helped her get seated, then he pulled her napkin from the table and handed it to her. “Champagne for you this afternoon?” he asked Weyland.

Weyland nodded. “Have you Taittinger, the Prelude Gran Crus?”

“Of course,” the old man said as he handed over menus before he walked away.

“Strange man,” Sorensen said. “Something in the eyes, I think.”

“Indeed. What did you see?” he asked.

“I’m not sure, but I’d say there’s more to him than meets the eye.”

“More what, do you think?”

“Power? Maybe the ability to facilitate, no, that’s not right…perhaps to meditate between warring factions?”

“I felt rank hostility.”

“Do you want to leave?” she asked.

“No. I want to understand.”

“Perhaps he simply hates tourists?”

“No, this is something deeper, like he’s done…like he’s hiding something monstrous. Something he’s done…in the past.”

A younger waiter returned with their champagne and took their orders, and curiously enough the old man was nowhere to be seen.

“So, did your father take you to the campus?”

“Yes, and I’ve been to the Wolfsschanze and the Berghof. He wanted to get me up to the Kehlsteinhaus but we ran out of time.”

“Indeed. You must’ve made quite an impression on a few people.”

She shrugged. “I found the facilities quite fascinating, especially the engineering campus.”

“Oh? Why fascinating?”

“Seriously? Well, for one thing, how about particle accelerators larger than CERNs. And, oh yeah, working ion drives for starships. Not spaceships, mind you, but starships…”

Weyland smiled because he hadn’t expected this reaction, or this level of exposure. He’d been expecting some kind of droning, daft airhead with no understanding of science at all, yet this woman seemed to be at least conversant in a few of the more important subjects being tackled in Argentina. Still, their work in New Zealand and French Polynesia had to remain off-limits, and he was to be the firewall that kept such secret projects from her. He shrugged as he innocently held his hands out: “If not us, then who?” he said, paraphrasing Hillel the Elder with a sly grin.

“I liked the Nick Land essay,” she said more seriously.

“Did you indeed?”

She nodded. “Any fool can look at our southern border and see how completely government has failed, but that’s just the most glaring example.”

“All democracies collapse,” Weyland said with a shrug, “and always under the weight of their internal inconsistencies. It is inevitable, but nevertheless America had a good run; she postponed the inevitable longer than most expected.”

“Longer than you expected?”

“My feelings are irrelevant.”

“Which means they are anything but,” she countered.

“Please don’t patronize me, Miss Sorensen. I’ve little tolerance for such obsequiousness.”

“Oh, that I do not doubt,” she said, the tone of her voice a direct challenge.

“Listen, I’m not sure I like the…” he started to say, but he stopped in mid-sentence when she closed her eyes and held her hands out to him.

“Take my hands,” she whispered.

“I’ll do no such thing…”

“Take my hands, now,” she said, her voice suddenly full of latent power, “and close your eyes.”

Curious now, he reached across their table and took her hands, and in the next instant he felt it. Nauseating vertigo, his heart spinning in a vacuum, then bitter cold. A deep, biting cold.

Then: “Open your eyes,” he heard her say.

And when he did he saw that he was at sea on a great ocean liner, now perched in a crow’s nest atop the ship’s foremast, and they were in deepest night. The ship was moving fast, fast enough to make his eyes water, and as the tears ran down his face they froze to the skin under his eyes. There were young men below playing some kind of football on the foredeck, and when he turned he saw the officers on watch talking to the helmsman inside the bridge.

“What have you…”

“Look there,” she said, pointing dead ahead.

He turned and in a heartbeat saw the iceberg. He heard the lookouts screaming “Iceberg, dead ahead,” and Peter Weyland forced himself to watch as his looming death approached. His heart was racing now, he urinated uncontrollably, and he fought the impulse to hide his eyes as the Titanic slammed into her appointment with destiny, then he turned to Sorensen, his voice full of panic, and he screamed “Get me out of here! Now, please!”

“Are you begging me, Dr Weyland? Begging me for your life?”

“Yes, please, I’m begging you! Get me away from this place!”

And in the next instant he felt himself crashing through furniture on the ristorante’s patio, this followed by huge, cascading waterfalls of near-freezing water and ragged chunks of blue ice that came crashing down with them. He heard screaming, saw the other people seated on the patio get up and run out onto the piazza, a few of them drenched from head to toe, then he took stock of his own situation: soaking wet and shivering, cuts on his forearms from the falling ice, and his heartbeat was still wildly out of control so he started taking deep breaths as he closed his eyes again.

But then the old man appeared.

And he walked straight up to Deborah, the fury in his eyes manifest, and as yet unspent.

“You must not do this here!” the old man hissed. “You must control these things!”

Weyland looked up at the old man, feeling like the bastard had suddenly grown two heads. “What did you say?”

“I said nothing to you, fool! Now the both of you, leave immediately, or there will be consequences!”

The words hit him like sharp physical blows and he shook his head, tried to clear his mind. “Who the devil do you think you are!” Weyland snarled as he pushed himself up from the floor, and now he turned to let the old man have it…

Until he saw the maelstrom in the creature’s eyes, a building cyclonic fury he had never seen before, not in anything, or anyone. The old man’s form was shimmering now, and raw, white gold power seeped from his skin, burning the air. Then the old man seemed to grow before their eyes, and he leaned close, his eyes dripping with molten malice: “Leave – while you still may. While I still let you…”

Weyland started to say something but he felt Sorensen take his hand and literally pull him away from the old man, then she was pulling him towards American Eagle. There were people waiting there, waiting for Weyland, she surmised, and when they saw him being pulled out of the ristorante they ran to his aid.

“Get him to a shower,” she said to them, clearly winded. “A hot shower, as fast as you can!”

Which turned out to be right there on the aft deck. Baris Metin popped the little cabinet door open and pulled out a shower head on a long metallic hose, then turned the hot water on and waited for it to warm, then Britney and Deborah held Weyland’s shivering body as the water poured over him, the bitter cold floating away on clouds of steam.

+++++

Ludvico – the Old Man – watched all this from his ristorante’s patio, a smile on his face. Two waiters walked up to him to see if he was alright, while others worked to clean up the ice from the floor and move all the ruined furniture from the patio. He saw the concern in their eyes and nodded.

“I’m alright now,” he sighed.

“Patron? What was that all about?”

He looked at the oldest and shook his head. “Have you ever killed a Nazi?” he asked the boy.

“Patron?”

“No, of course you haven’t, but what a pity. I did love doing so, once upon a time.”

The boys stood back and watched as Ludvico went to the cloakroom; he came out a moment later in his green loden cape, and he also had his cane, the fancy wooden one with the silver filigree, and that could only mean one thing…

“I know it’s a little early for passegiatta, but I think I shall walk out to the rocks.”

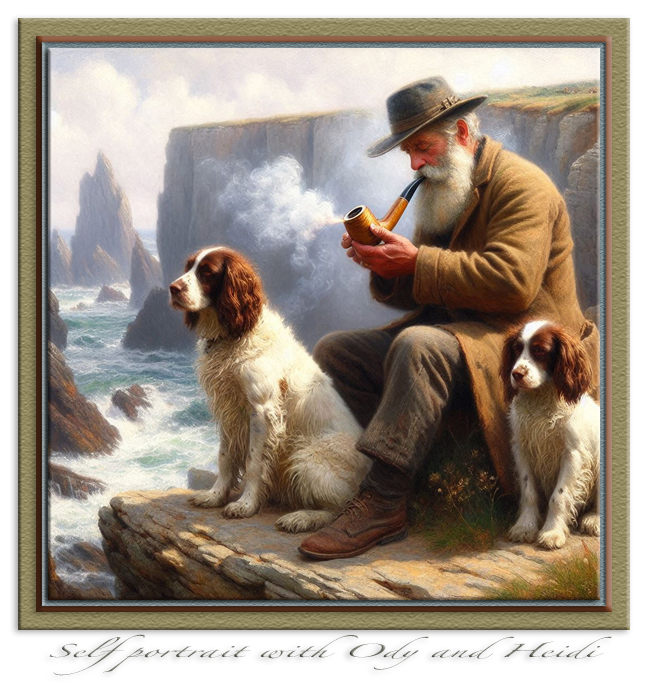

Ludvico walked along the Molo Umberto past the dozens of little motorboats tied-off to the ancient stone sea wall, and then he came to Diogenes, to Malcolm Doncaster hunting and pecking his way across his little laptop’s keyboard. “Good afternoon, Poet!” the old man called out to his friend.

Startled, Doncaster looked up and smiled when he saw his Ludvico. “It’s a little early for passegiatta, isn’t it?”

“Not today,” Ludvico sighed.

“Ah, yes indeed. Well, I suspect Elsie is in need of a little exercise. Care for some company?”

“Yes, please. Ah, Berensen, is that you, my friend?”

Lev stood from Sonata’s cockpit table and shut down his laptop. “Who is that asshole?” Podgolski said, pointing at American Eagle.

“Oh, just your basic run-of-the-mill Nazi,” Ludvico said, smiling broadly now.

“Here? Now?” Lev said, now getting into the swing of things. “My, my, where’s Mel Brooks when you really need him…?”

“Come on,” Ludvico sighed, finally relaxing a little, “we’re going out to the rocks.”

“Should I bring towels?”

“Damn right you should,” Doncaster growled, his bulldog jowls flapping on the breeze. “And one for the dog, damnit all!”

© 2024 adrian leverkühn | abw | adrianleverkuhnwrites.com | this is fiction plain and simple, and nothing but.

Okay, take me to the pilot, wouldya? Or, maybe we should be walking the dogs?

Nice one, what is it with you and Portofino?

LikeLike

Just one of those things, I guess.

LikeLike